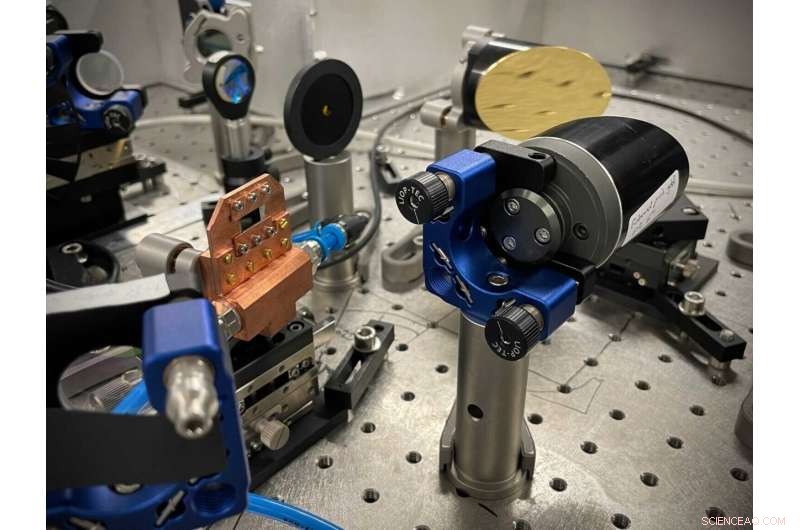

Halvledarnanoskivorna i det vattenkylda kopparfästet förvandlar en infraröd laserpuls till en effektivt unipolär terahertzpuls. Teamet säger att deras terahertz-sändare kunde göras för att passa in i en tändsticksask. Kredit:Christian Meineke, Huber Lab, University of Regensburg

En laserpuls som kringgår ljusvågornas inneboende symmetri kan manipulera kvantinformation och potentiellt föra oss närmare rumstemperaturkvantberäkning.

Studien, ledd av forskare vid University of Regensburg och University of Michigan, kan också påskynda konventionell datoranvändning.

Quantum computing har potential att påskynda lösningar på problem som behöver utforska många variabler samtidigt, inklusive upptäckt av läkemedel, väderförutsägelser och kryptering för cybersäkerhet. Konventionella datorbitar kodar antingen en 1 eller 0, men kvantbitar eller kvantbitar kan koda båda samtidigt. Detta gör i huvudsak att kvantdatorer kan arbeta igenom flera scenarier samtidigt, snarare än att utforska dem efter varandra. Dessa blandade tillstånd varar dock inte länge, så informationsbehandlingen måste vara snabbare än vad elektroniska kretsar kan uppbåda.

Medan laserpulser kan användas för att manipulera energitillstånden för qubits, är olika sätt att beräkna möjliga om laddningsbärare som används för att koda kvantinformation skulle kunna flyttas runt - inklusive en rumstemperaturmetod. Terahertz-ljus, som sitter mellan infraröd och mikrovågsstrålning, svänger tillräckligt snabbt för att ge hastigheten, men vågens form är också ett problem. Elektromagnetiska vågor är nämligen skyldiga att producera svängningar som är både positiva och negativa, som summerar till noll.

Den positiva cykeln kan flytta laddningsbärare, såsom elektroner. Men sedan drar den negativa cykeln laddningarna tillbaka till där de började. För att på ett tillförlitligt sätt kontrollera kvantinformationen behövs en asymmetrisk ljusvåg.

"Det optimala skulle vara en helt riktad, unipolär "våg", så det skulle bara finnas den centrala toppen, inga svängningar. Det skulle vara drömmen. Men verkligheten är att ljusfält som utbreder sig måste svänga, så vi försöker göra the oscillations as small as we can," said Mackillo Kira, U-M professor of electrical engineering and computer science and leader of the theory aspects of the study in Light:Science &Applications .

Since waves that are only positive or only negative are physically impossible, the international team came up with a way to do the next best thing. They created an effectively unipolar wave with a very sharp, high-amplitude positive peak flanked by two long, low-amplitude negative peaks. This makes the positive peak forceful enough to move charge carriers while the negative peaks are too small to have much effect.

They did this by carefully engineering nanosheets of a gallium arsenide semiconductor to design the terahertz emission through the motion of electrons and holes, which are essentially the spaces left behind when electrons move in semiconductors. The nanosheets, each about as thick as one thousandth of a hair, were made in the lab of Dominique Bougeard, a professor of physics at the University of Regensburg in Germany.

Then, the group of Rupert Huber, also a professor of physics at the University of Regensburg, stacked the semiconductor nanosheets in front of a laser. When the near-infrared pulse hit the nanosheet, it generated electrons. Due to the design of the nanosheets, the electrons welcomed separation from the holes, so they shot forward. Then, the pull from the holes drew the electrons back. As the electrons rejoined the holes, they released the energy they'd picked up from the laser pulse as a strong positive terahertz half-cycle preceded and followed by a weak, long negative half-cycle.

"The resulting terahertz emission is stunningly unipolar, with the single positive half-cycle peaking about four times higher than the two negative ones," Huber said. "We have been working for many years on light pulses with fewer and fewer oscillation cycles. The possibility of generating terahertz pulses so short that they effectively comprise less than a single half-oscillation cycle was beyond our bold dreams."

Next, the team intends to use these pulses to manipulate electrons in room temperature quantum materials, exploring mechanisms for quantum information processing. The pulses could also be used for ultrafast processing of conventional information.

"Now that we know the key factor of unipolar pulses, we may be able to shape terahertz pulses to be even more asymmetric and tailored for controlling semiconductor qubits," said Qiannan Wen, a Ph.D. student in applied physics at U-M and a co-first-author of the study, along with Christian Meineke and Michael Prager, Ph.D. students in physics at the University of Regensburg. + Utforska vidare