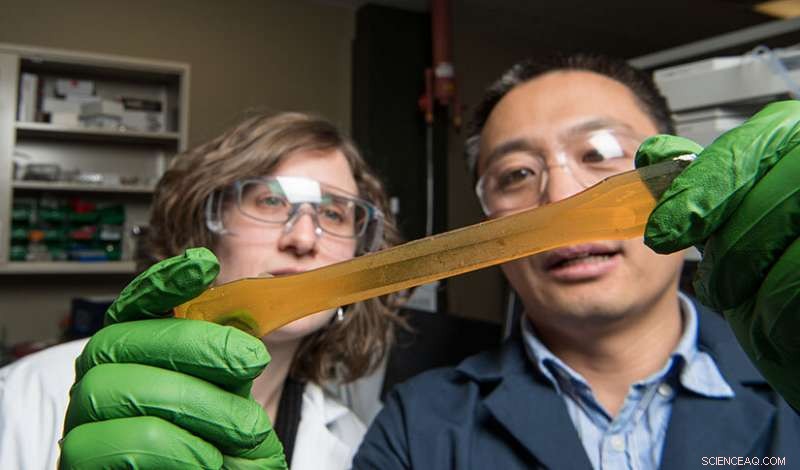

En banbrytande förnybar formel-NREL-forskaren Tao Dong (höger) och tidigare praktikanten Stephanie Federle (vänster) undersöker biobaserade, icke -toxiskt polyuretanharts, ett lovande alternativ till konventionell polyuretan. Upphovsman:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Utan det, världen kan vara lite mindre mjuk och lite mindre varm. Våra fritidskläder kan kasta mindre vatten. Innersulorna i våra sneakers kanske inte ger samma terapeutiska stöd för bågen. Träkornet i färdiga möbler kanske inte "poppar".

Verkligen, polyuretan - en vanlig plast i applikationer som sträcker sig från sprutbara skum till lim till syntetiska klädfibrer - har blivit en häftklammer i 2000 -talet, lägga till bekvämlighet, bekvämlighet, och till och med skönhet till många aspekter av vardagen.

Materialets stora mångsidighet, som för närvarande till stor del tillverkas av biprodukter från petroleum, har gjort polyuretan till plasten för en rad produkter. I dag, mer än 16 miljoner ton polyuretan produceras globalt varje år.

"Mycket få aspekter av våra liv berörs inte av polyuretan, "återspeglade Phil Pienkos, en kemist som nyligen gick i pension från National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) efter nästan 40 års forskning.

Men Pienkos-som byggde en karriär för att undersöka nya sätt att producera biobaserade bränslen och material-sa att det finns en växande drivkraft för att tänka om hur polyuretan produceras.

"Nuvarande metoder är till stor del beroende av giftiga kemikalier och icke-förnybar petroleum, "sa han." Vi ville utveckla en ny plast med alla användbara egenskaper hos konventionell poly men utan de dyra miljömässiga biverkningarna. "

Var det möjligt? Resultat från laboratoriet ger ett rungande ja.

Genom en ny kemi som använder icke -toxiska resurser som linolja, spillfett, eller till och med alger, Pienkos och hans NREL -kollega Tao Dong, en expert på kemiteknik, har utvecklat en banbrytande metod för att producera förnybar polyuretan utan giftiga prekursorer.

Det är ett genombrott med potential att gröna marknaden för produkter som sträcker sig från skor, till bilar, till madrasser, och vidare.

Men för att förstå den stora vikten av prestationen, det är bra att titta tillbaka på hur det vetenskapliga framsteget uppstod, en historia som vandrar från de kemiska grunderna för konventionell polyuretan, in i algelabbet där en idé för en ny kemi först dök upp, och slingrar sig fram till nya företagspartnerskap som sätter scenen för en lovande framtid för kommersialisering.

En fråga om kemi

När polyuretan först blev kommersiellt tillgängligt på 1950 -talet, det växte snabbt i popularitet för användning i många produkter och applikationer. Det berodde inte minst på materialets dynamiska och avstämbara egenskaper, liksom tillgängligheten och överkomligheten för de petroleumbaserade komponenterna som används för att göra den.

Genom en smart kemisk process som använder polyoler och isocyanater - de grundläggande byggstenarna i konventionella polyuretaner - kan tillverkarna skräddarsy sina formuleringar för att producera en fantastisk variation av polyuretanmaterial, var och en med unika och användbara egenskaper.

Tillverkad av en långkedjig polyol, till exempel, kan ge flexibla skum för en mjuk madrass. En annan formulering kan ge en rik vätska som, när de sprids på möbler, både skyddar och avslöjar den inneboende skönheten i träkorn. En tredje sats kan innehålla koldioxid (CO 2 ) för att expandera materialet, producerar ett sprutbart skum som torkar till stel och porös isolering, perfekt för att hålla värmen i ett hem.

"Det är det fina med isocyanat, "sade Dong när han reflekterade över konventionell polyuretan, "dess förmåga att bilda skum."

Men Dong sa att isocyanater medför betydande nackdelar, för. Även om dessa kemikalier har snabba reaktivitetshastigheter, gör dem mycket anpassningsbara för många branschapplikationer, de är också mycket giftiga, och de är framställda av ett ännu giftigare råmaterial, fosgen. Vid inandning, isocyanater kan leda till en rad negativa hälsoeffekter, som hud, öga, och irritation i halsen, astma, och andra allvarliga lungproblem.

"Om produkter som innehåller konventionella polyuretaner bränns, dessa isocyanater förångas och släpps ut i atmosfären, "Pienkos tillagt. Även helt enkelt spruta polyuretan för användning som isolering, Pienkos sa, kan aerosolisera isocyanat, kräver att arbetstagare vidtar försiktighetsåtgärder för att skydda sin hälsa.

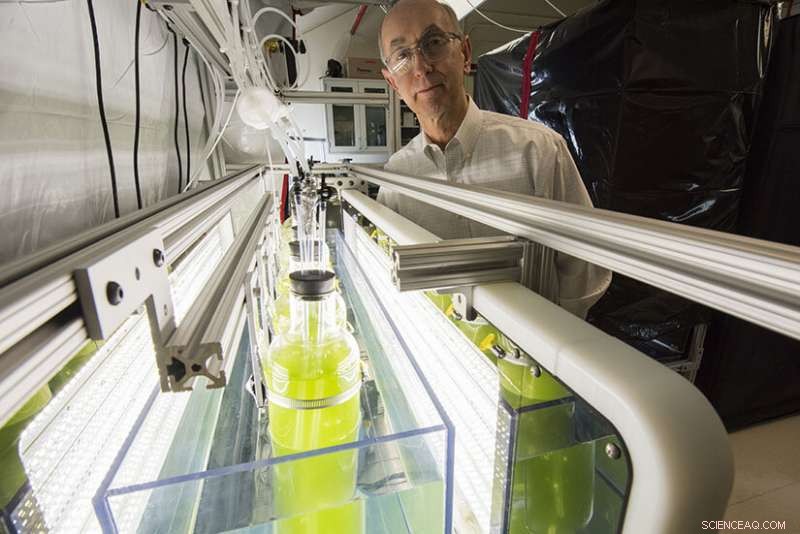

Nyligen pensionerad, Phil Pienkos (bilden) grundade ett nytt företag, Polaris Renewables, för att påskynda kommersialiseringen av den nya polyuretanen, an idea that originally grew out of his algae biofuel research at NREL. Upphovsman:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

To try and tackle these and other issues—such as reliance on petrochemicals—scientists from labs around the world have begun looking for new ways to synthesize polyurethane using bio-based resources. But these efforts have largely had mixed results. Some lacked the performance needed for industry applications. Others were not completely renewable.

The challenge to improve polyurethane, sedan, remained ripe for innovation.

"We can do better than this, " thought Pienkos five years ago when he first encountered the predicament. Energized by the opportunity, he joined with Dong and Lieve Laurens, also of NREL, on a search for a better polyurethane chemistry.

Rethinking the Building Blocks of Polyurethane

The idea grew from a seemingly unrelated laboratory problem:lowering the cost of algae biofuels. As with many conventional petrochemical refining processes, biofuel refiners look for ways to use the coproducts of their processes as a source of revenue.

The question becomes much the same for algae biorefining. Can the waste lipids and amino acids from the process become ingredients for a prized recipe for polyurethane that is both renewable and nontoxic?

For Dong, answering the question at the basic chemical level was the easy part—of course they could. Scientists in the 1950s had shown it was possible to synthesize polyurethane from non-isocyanate pathways.

The real challenge, Dong said, was figuring out how to speed up that reaction to compete with conventional processes. He needed to produce polymers that performed at least as well as conventional materials, a major technical barrier to commercializing bio-based polyurethanes.

"The reactivity of the non-isocyanate, bio-based processes described in the literature is slower, " Dong explained. "So we needed to make sure we had reactivity comparable to conventional chemistry."

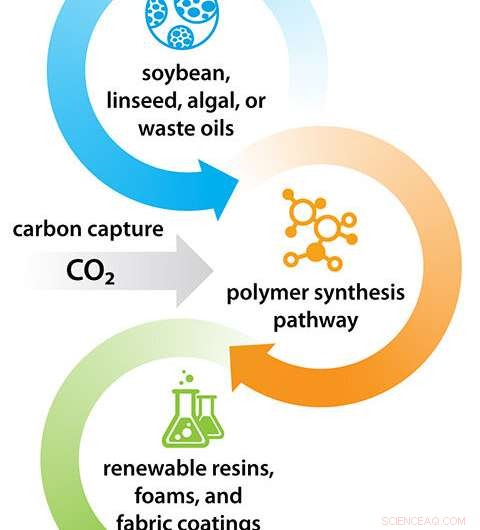

NREL's process overcomes the barrier by developing bio-based formulas through a clever chemical process. It begins with an epoxidation process, which prepares the base oil—anything from canola oil or linseed oil to algae or food waste—for further chemical reactions. By reacting these epoxidized fatty acids with CO 2 from the air or flue gas, carbonated monomers are produced. Lastly, Dong combines the carbonated monomers with diamines (derived from amino acids, another bio-based source) in a polymerization process that yields a material that cures into a resin—non-isocyanate polyurethane.

By replacing petroleum-based polyols with select natural oils, and toxic isocyanates with bio-based amino acids, Dong had managed to synthesize polymers with properties comparable to conventional polyurethane. Med andra ord, he had developed a viable renewable, nontoxic alternative to conventional polyurethane.

And the chemistry had an added environmental benefit, för.

"As much of 30% by weight of the final polymer is CO 2 , " Pienkos said, adding that the numbers are even more impressive when considering the CO 2 absorbed by the plants or algae used to create the oils and amino acids in the first place.

CO 2 , a ubiquitous greenhouse gas, is often considered an unfortunate waste product of various industrial processes, prompting many companies to look for ways to absorb it, eliminate it, or even put it to good use as a potential source of profit. By incorporating CO 2 into the very structure of their polyurethane, Pienkos and Dong had provided a pathway for boosting its value.

"That means less raw material per pound of polymer, lägre kostnad, and a lower overall carbon footprint, " Pienkos continued. "It looks to us that this offers remarkable sustainability opportunities."

A Sought-After Renewable Solution Finds Its Commercial Feet

The next step was to see if the process could be commercialized, scaled up to meet the demands of the market.

The building blocks of poly—NREL's chemistry reacts natural oils with readily available carbon dioxide to produce renewable, nontoxic polyurethanes—a pathway for creating a variety of green materials and products. Kredit:National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Trots allt, renewable or not, polyurethane needs to demonstrate the properties that consumers expect from brand-name products. The process to create it must also match companies' manufacturing processes, allowing them to "drop in" the new material without prohibitively costly upgrades to facilities or equipment.

"That's why we need to work with industry partners, " Dong explained, "to make sure our research aligns with their manufacturing processes."

In the two short years since Pienkos and Dong first demonstrated the viability of producing fully renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, several companies have already contributed resources and research partnerships in the push for its commercialization.

A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy Technology Commercialization Fund award, till exempel, brought in $730, 000 of federal funding to help develop the technology, as well as matching "in kind" cost share from the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, the mattress company Tempur Sealy, and a start-up biotechnology company called Algix.

And Pienkos says companies from other industries have shown preliminary interest, för. "These companies believe there is promise in this, " han sa.

Their interest could partly be due to the tunability of Pienkos and Dong's approach, which lets them, much like conventional methods, create polymers that match industry standards.

"We've demonstrated that the chemistry is tunable, " Dong said. "We can control the final performance through our approach."

By controlling the epoxidation process or amount of carbonization, till exempel, the process can be suited to meet the performance needs of a product. That may give the outsoles of a pair of running shoes enough flexibility and strength to endure many miles pounding into hot or cold asphalt. Or it may give a mattress a balance of stiffness and support.

"It's got regulation push. It's got market pull. It's got the potential to compete with non-renewables on the basis of cost. It's got a lower carbon footprint. It's got everything, " Pienkos said of the opportunities for commercialization. "This became the most exciting aspect of my career at NREL. Så, when I retired, I decided that I want to make this real. I want to see this technology actually make it into the marketplace."

After retiring last April, Pienkos went on to establish a company, Polaris Renewables, to help accelerate the commercialization of the novel polyurethane. Så, while he continues with his responsibilities as an NREL emeritus researcher, he is also doing outreach to industry to find additional corporate partners, especially in the fashion industry through the international sustainability initiative Fashion for Good.

"In the fashion industry, customers are demanding sustainability, " he explained. "They will pay something of a green premium if you can demonstrate a lower carbon footprint, better end of life disposition."

Verkligen, for both Pienkos and Dong, the breakthrough in renewable, nontoxic polyurethane has become more than an exciting scientific venture. It offers the world a pathway for products that leave a lighter mark on the environment.

"I think this is a great opportunity to solve the plastic pollution problem, " Dong said. "We need to save our environment, and part of that begins with making plastic renewable."

Pienkos, för, thinks that a commercial success in this venture could be a catalyst that spurs further growth and further success in bringing renewable, greener products to the market.

"This could be a success story for NREL, " he said. "A success here means a great deal to the world."

I detta fall, success might be measured in more than the affordability of the production process or the carbon uptake of the polyurethane chemistry. In a world with NREL's renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, success might be something we can truly feel in the durability of our clothing, in the comfort our shoes provide, or in the rejuvenation we feel after sleeping on a memory foam mattress.