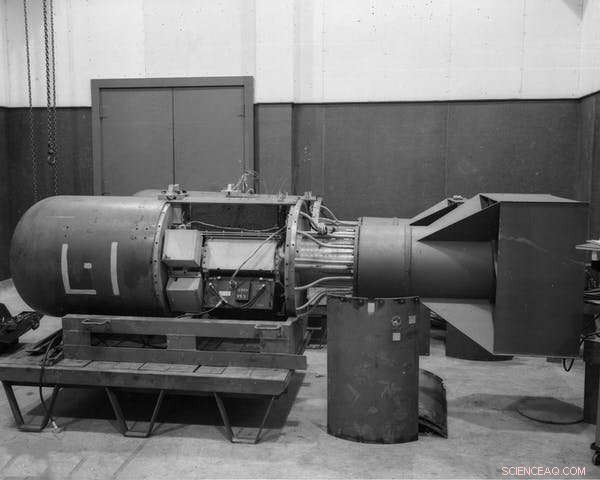

Atombomben med kodnamnet "Little Boy", samma typ släpptes senare på Hiroshima, vid Los Alamos National Laboratory 1944. Kredit:Shutterstock

Om mindre än 24 timmar kommer Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists att uppdatera Doomsday Clock. Det är för närvarande 100 sekunder från midnatt - den metaforiska tidpunkten då människosläktet kunde förstöra världen med teknologier av egen tillverkning.

Händerna har aldrig tidigare varit så nära midnatt. Det finns knappt hopp om att det ska återgå till vad som kommer att vara dess 75-årsjubileum.

Häng med oss för 75-årsjubileet Doomsday Clock tillkännagivande torsdagen den 20 januari kl. 10:00 EST

Detaljer:https://t.co/UgE8wtUvND pic.twitter.com/RyWu91AnfP

— Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (@BulletinAtomic) 9 januari 2022

Klockan skapades ursprungligen som ett sätt att uppmärksamma kärnvapenbrand. Men forskarna som grundade Bulletin 1945 var mindre fokuserade på den initiala användningen av "bomben" än på det irrationella i att lagra vapen för kärnvapenhegemonins skull.

De insåg att fler bomber inte ökade chanserna att vinna ett krig eller gjorde någon säker när bara en bomb skulle räcka för att förstöra New York.

Även om kärnvapenförintelse fortfarande är det mest sannolika och akuta existentiella hotet mot mänskligheten, är det nu bara en av de potentiella katastroferna som Domedagsklockan mäter. Som Bulletin uttrycker det:"Klockan har blivit en universellt erkänd indikator på världens sårbarhet för katastrofer från kärnvapen, klimatförändringar och störande teknologier på andra områden."

Flera anslutna hot

På ett personligt plan känner jag en viss känsla av akademisk släktskap med klocktillverkarna. Mina mentorer, särskilt Aaron Novick, och andra som djupt påverkade hur jag ser min egen vetenskapliga disciplin och inställning till vetenskap, var bland dem som bildade och gick med i den tidiga Bulletinen.

År 2022 sträcker sig deras varning bortom massförstörelsevapen och inkluderar andra tekniker som koncentrerar potentiella existentiella faror – inklusive klimatförändringar och dess grundorsaker i överkonsumtion och extremt välstånd.

Många av dessa hot är redan välkända. Till exempel är kommersiell kemikalieanvändning all genomträngande, liksom det giftiga avfall det skapar. Det finns tiotusentals storskaliga avfallsplatser bara i USA, med 1 700 farliga "superfondplatser" prioriterade för sanering.

Som orkanen Harvey visade när den drabbade Houston-området 2017 är dessa platser extremt sårbara. An estimated two million kilograms of airborne contaminants above regulatory limits were released, 14 toxic waste sites were flooded or damaged, and dioxins were found in a major river at levels over 200 times higher than recommended maximum concentrations.

That was just one major metropolitan area. With increasing storm severity due to climate change, the risks to toxic waste sites grow.

At the same time, the Bulletin has increasingly turned its attention to the rise of artificial intelligence, autonomous weaponry, and mechanical and biological robotics.

The movie clichés of cyborgs and "killer robots" tend to disguise the true risks. For example, gene drives are an early example of biological robotics already in development. Genome editing tools are used to create gene drive systems that spread through normal pathways of reproduction but are designed to destroy other genes or offspring of a particular sex.

Climate change and affluence

As well as being an existential threat in its own right, climate change is connected to the risks posed by these other technologies.

Both genetically engineered viruses and gene drives, for example, are being developed to stop the spread of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes, whose habitats spread on a warming planet.

Once released, however, such biological "robots" may evolve capabilities beyond our ability to control them. Even a few misadventures that reduce biodiversity could provoke social collapse and conflict.

Similarly, it's possible to imagine the effects of climate change causing concentrated chemical waste to escape confinement. Meanwhile, highly dispersed toxic chemicals can be concentrated by storms, picked up by floodwaters and distributed into rivers and estuaries.

The result could be the despoiling of agricultural land and fresh water sources, displacing populations and creating "chemical refugees."

Resetting the clock

Given that the Doomsday Clock has been ticking for 75 years, with myriad other environmental warnings from scientists in that time, what of humanity's ability to imagine and strive for a different future?

Part of the problem lies in the role of science itself. While it helps us understand the risks of technological progress, it also drives that process in the first place. And scientists are people, too—part of the same cultural and political processes that influence everyone.

J. Robert Oppenheimer—the "father of the atomic bomb"—described this vulnerability of scientists to manipulation, and to their own naivete, ambition and greed, in 1947:"In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose."

If the bomb was how physicists came to know sin, then perhaps those other existential threats that are the product of our addiction to technology and consumption are how others come to know it, too.

Ultimately, the interrelated nature of these threats is what the Doomsday Clock exists to remind us of.