Kredit:Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

Science fiction rymdfilmer kan göra ett dåligt jobb med att utbilda människor om rymden. I filmerna, hotshotade piloter dirigerar sina duellerande rymdskepp genom rymden som om de flyger genom en atmosfär. De bankar och vänder och utför loopar och rullar, kanske kasta in en snabb Immelman-sväng, som om de är föremål för jordens gravitation. Är det realistiskt?

Nej.

I verkligheten, en rymdstrid kommer sannolikt att se mycket annorlunda ut. Med en ökande närvaro i rymden, och potentialen för framtida konflikter, är det dags att tänka på hur en faktisk rymdstrid skulle se ut?

Det ideella Aerospace Corporation tycker att det är dags att fundera över hur en riktig rymdstrid skulle se ut. Dr. Rebecca Reesman från Aerospace Corporations Center for Space Policy and Strategy och hennes kollega James R. Wilson har skrivit en artikel om ämnet rymdstrider, med titeln "The Physics of Space War:How Orbital Dynamics Constrain Space-to-Space Engagement."

Om tidigare mänskliga angelägenheter indikerar framtiden, då kommer militariseringen av rymden att fortsätta. Det är trots prat om att hålla rymden fredlig, och trots fördrag som säger detsamma. Så det är viktigt att allt eftersom fler nationer ökar sin närvaro i rymden, och när en konkurrens om resurser börjar orsaka problem, att samtalet kring rymdkonflikt tar en realistisk vändning.

Det är så som författarna gör i inledningen till sin uppsats. "När USA och världen diskuterar möjligheten att konflikter sträcker sig ut i rymden, det är viktigt att ha en allmän förståelse för vad som är fysiskt möjligt och praktiskt. Scener från Star Wars, böcker och TV-program skildrar en värld som skiljer sig mycket från vad vi sannolikt kommer att se under de kommande 50 åren, om någonsin, med tanke på fysikens lagar."

En sovjetisk Almaz-bemannad rymdstation vid Cosmonautics and Aviation Center i Moskva. Ryssland designade flera typer av militära satelliter och rymdstationer, några beväpnade med ett maskingevär, innan man överger idén som för dyr. Kredit:Av Pulux11 – Eget arbete, CC BY-SA 4.0

Det har aldrig varit en strid i rymden ännu. Men det har förekommit en del vapentestning. Kina arbetar med anti-satellitvapen och har testat en anti-satellitmissil. Så även Indien. Ryssland arbetar också med anti-satellitkapacitet, och USA gör detsamma. USA förstörde faktiskt en av sina egna satelliter med en missil redan 1985.

Detta är sannolikt bara toppen av isberget när det kommer till framtida konflikter i rymden. Ingen av denna anti-satellitaktivitet involverade människor som färdades i rymdfarkoster, och det kanske aldrig kommer att behövas bemannade militära rymdfarkoster, enligt tidningen. "Rymden till rymden engagemang i en modern konflikt skulle utkämpas enbart med obemannade fordon som kontrolleras av operatörer på marken och starkt begränsade av de begränsningar som fysiken sätter för rörelse i rymden."

I rymdålderns tidiga dagar, medan det kalla kriget fortfarande rasade, supermakterna föreställde sig att konflikter i rymden till stor del skulle vara en förlängning av jordiska konflikter. Sovjeterna designade till och med rymdstationer beväpnade med ett maskingevär för att försvara sig mot attacker från amerikanska astronauter. USA arbetade med liknande idéer.

Men tekniska framsteg gjorde att dessa ansträngningar övergavs till förmån för obemannade satelliter. "Så småningom, båda programmen vacklade. Istället, förbättringar av teknik och dataöverföring – samma utveckling som i slutändan ligger till grund för vårt moderna uppkopplade liv – möjliggjorde satelliter som utför samma militära funktioner som man tänkt sig för de tidigare besättningsprogrammen." rymden domineras av satelliter, med endast ISS som är värd för människor.

Detta kommer att bli framtiden, enligt tidningen. Under de kommande 50 åren eller så, alla konflikter i rymden kommer att involvera attacker mot satelliter. Men allt blir inte en direkt attack. Författarna beskriver fyra mål i en rymdattack:

Rymdstrider kommer sannolikt att vara mellan satelliter, och tankning kommer inte att vara ett alternativ. På den här bilden, en F-16 tankar från en KC-135 Stratotanker. Kredit:Av U.S. Air Force

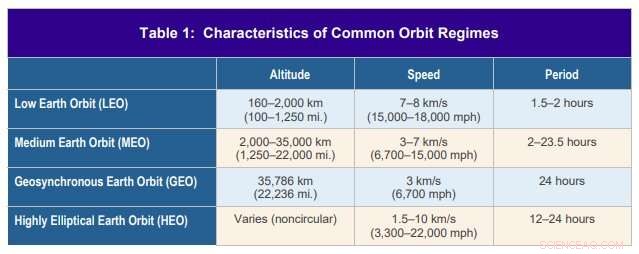

Satelliter rör sig mycket förutsägbart. De rör sig snabbt, men det är relativt lätt att förutsäga deras framtida position och att avlyssna dem, i många fall. Vissa satelliter kan ändra sin omloppshöjd, men de har ingen verklig manövrerbarhet och nästan inget sätt att undvika en attack.

"För att beskriva hur fysiken skulle begränsa engagemang från rymden till rymden, denna artikel beskriver fem nyckelbegrepp:satelliter rör sig snabbt, satelliter rör sig förutsägbart, utrymmet är stort, timing är allt, och satelliter manövrerar långsamt."

Att flyga genom jordens atmosfär är inte helt enkelt, men det är ganska intuitivt. Men i rymden, det är helt annorlunda och kallas inte exakt flygning. Utan atmosfär och låg gravitation, saker är väldigt olika. "Rörelse i rymden är kontraintuitiv för dem som är vana vid att flyga i jordens atmosfär och chansen att tanka, " skriver författarna.

"Space-to-space-engagemang skulle vara avsiktligt och sannolikt utvecklas långsamt eftersom rymden är stor och rymdfarkoster kan fly sina förutsägbara vägar endast med stor ansträngning. Dessutom, attacker på rymdtillgångar skulle kräva precision eftersom rymdfarkoster och till och med markbaserade vapen kan engagera mål i rymden först efter att komplexa beräkningar har fastställts i en mycket konstruerad domän." Det skulle inte finnas någon kader av stridspiloter i beredskap, väntar på att klättra och snabbt starta. Istället, en rymdstrid som involverar satelliter är mer en matematisk övning.

Satellitbanor är förutsägbara och beror inte på satellitens massa. Kredit:Reesman och Wilson 2020.

"This is true because physics puts constraints on what happens in space. Only by mastering these constraints can other questions such as how to fight and, viktigast, when and why to fight a war in space, be explored, " de skriver.

A satellite's orbit is predictable because of the relationship between speed, altitude and the orbit's shape. At lower altitudes, satellites can experience atmospheric drag. Också, the Earth isn't a perfect sphere. But those factors can be accounted for in an attack. "To deviate from their prescribed orbit, satellites must use an engine to maneuver. This contrasts with airplanes, which mostly use air to change direction; the vacuum of space offers no such option, " de skriver.

The sheer volume of space is also a factor in a space battle. "The volume of space between LEO and GEO is about 200 trillion cubic kilometers (50 trillion cubic miles). That is 190 times bigger than the volume of Earth."

So tracking satellites accurately in that volume of space will be a continuous challenge, since some will be designed to be undetected. But that's not impossible; satellites are regularly tracked. And since they're not very maneuverable, once a satellite's orbit is detected, monitors can keep track of its trajectory.

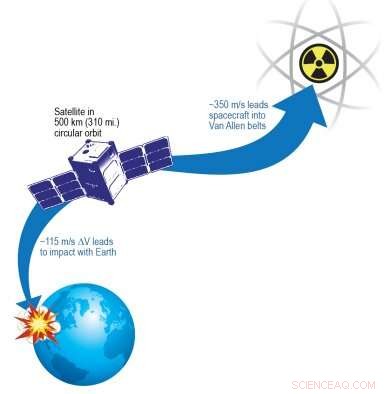

The sheer volume of space also means that most space battles would be very short-lived. There won't be any dogfights. "Space is big, which means that a space-to-space engagement is not going to be both intense and long. It can only be one or the other:either a short, intense use of a lot of Delta V for big effect or long, deliberate use of Delta V for smaller or persistent effects."

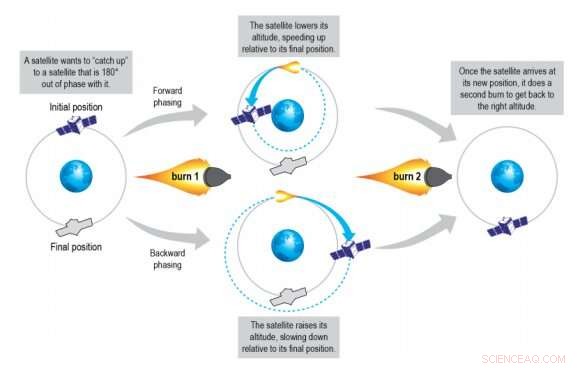

Satellites change their position in their orbit with phasing maneuvers. Any time a satellite raises its orbit, it slows down and appears to be moving backward in relation to its prior orbit and altitude. This is how a satellite can “catch up” to another satellite. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

Delta V is a change in velocity, and that requires fuel or propellant. But most satellites don't have the capability to change their velocity, and the few that might are severely fuel-limited.

"Operators of an attack satellite may spend weeks moving a satellite into an attack position during which conditions may have changed that alter the need for or the objective of the attack." And if the defending satellite is able to only slightly change its own path in response to an attack, then the attacking satellite may not have the capability or the fuel to change its own path to intercept it.

The authors also point out that timing is everything. Even if an attacking satellite can orient itself into the same orbital path as its target, there's still no guarantee of proximity.

"The nature of conflict often requires two competing weapons systems to get close to one another, " the report says. The authors use the example of an aircraft carrier needing to get close to its target, and another of jet fighters that also need to be close to each other. The same thing is true of satellites in space.

"Getting two satellites to the same altitude and the same plane is straightforward (though time and ?V consuming), but that does not mean they are yet in the same spot. The phasing—current location along the orbital trajectory—of the two satellites must also be the same. Since speed and altitude are connected, getting two satellites in the same spot is not intuitive." Instead, it takes perfect timing and meticulous preparation.

If a satellite performs a forward phasing maneuver with a first burn of 115 m/s or more of ?V, it will reenter Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. Liknande, if the satellite performs a backward phasing maneuver with a first burn of 350 m/s or more of ?V, it will experience high radiation in the Van Allen belts. These two facts create natural bounds for how quickly a satellite can maneuver in LEO (500 km or 310 mi.). Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

The authors also discuss another method of approaching a target called "plane matching, " A satellite maneuvers itself so that its orbital plane is aligned with a target. That has the advantage of allowing the attacker to dictate the time of the engagement. "By not initiating threatening maneuvers immediately, an attacker may try to seem harmless while waiting for an optimal time to attack, " the authors explain.

But none of these maneuvers happen quickly. "The physics of space dictate that kinetic space-to-space engagements be deliberate with satellites maneuvering for days, if not weeks or months, beforehand to get into position to have meaningful operational effects, " they write. But it can still be done.

And once the interception has been set up, "…many opportunities can arise to maneuver close enough to engage a target quickly."

There are natural limits to how maneuvering satellites in LEO can do. Å ena sidan, some phasing maneuvers can send the satellite into the Earth's atmosphere where it will be burned up. På den andra, it could be sent too far away from LEO, into the Van Allen Belts. So there are constraints on a satellite's maneuverability.

Satellites in geostationary orbits maintain the same relative position over Earth, so some of the mechanics of attacking and defending are different. Men totalt sett, the same constraints are still in place. It takes time and energy to maneuver in space, regardless of the type of orbit.

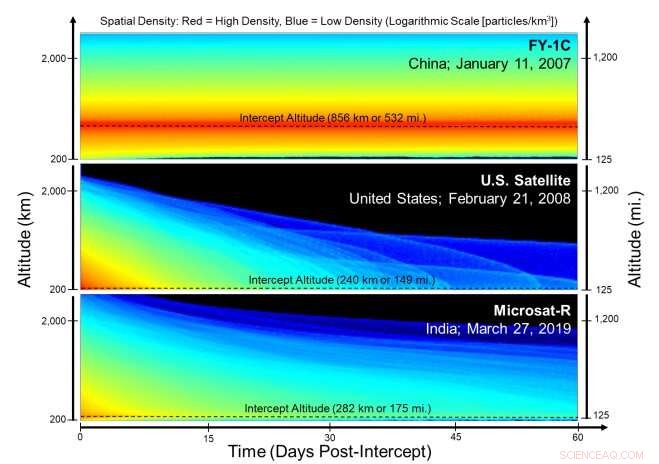

The density of debris is compared at different altitudes as a function of time after the ASAT intercepted (made contact with and destroyed) the target satellite. The Chinese test happened at a much higher altitude (856 km or 532 mi.) than the other two, creating long-lasting debris. Credit:Reesman and Wilson, 2020

But orbital and maneuverability considerations are only a part of what the report addresses.

The authors go on to discuss the types of attacks that can take place. Collisions, projectiles, and electronic jamming or disruption are covered in the paper. Each type has its own considerations and preparations.

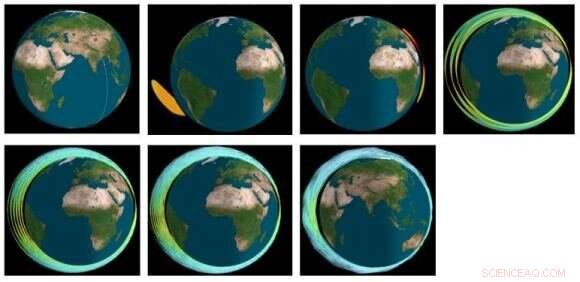

But the authors also discuss the aftermath of some successful attacks:complications arising from debris. Additional debris could end up damaging other unintentional targets, like the attacker's own satellites or those of a neutral nation. There have been three successful anti-satellite attacks:one by China, one by the U.S., och Indien. The authors prepared a graphic to show the debris from each one.

The debris cloud from an attack is denser immediately after the attack and spreads out quickly. Even though debris density is lowered quickly, the debris spreads out over a larger area and is still hazardous.

The paper is a clear presentation of all of the difficulties with space battles and how much different they would be compared to air-to-air battles. But some other considerations that are still important are outside its scope.

This image shows the debris cloud from the Indian ASAT in 2019. The panels show the cloud at 5 min., 45 min., 90 min., 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 6 days after the attack. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

What happens when one nation deduces that their satellites are about to be attacked? They won't sit on their thumbs. They'll likely denounce, threaten, and even retaliate here on Earth. A space attack could end up being a flashpoint for another terrestrial war.

There could end up being an arms race in space, where nations compete to outspend each other on space weaponry and other technology. That's a huge strain on resources for a world that should be focused on meeting the challenge of climate change.

Och, where does it all end? War in orbit? War on the moon? War on Mars? When will humanity figure it out and just stop?

En dag, maybe, there'll be a final war before we give it all up. But that won't likely be in the next 50 years.

And if there is a war in the next 50 years or so, it may involve satellites, and it may look a lot like how the authors of this report have laid it out:slow, calculated, and deliberate.