Forntida alkemister försökte göra bly och andra vanliga metaller till guld och platina. Moderna kemister i Paul Chiriks laboratorium i Princeton förvandlar reaktioner som har berott på miljövänliga ädelmetaller, hitta billigare och grönare alternativ för att ersätta platina, rodium och andra ädelmetaller vid läkemedelsproduktion och andra reaktioner.

De har hittat ett revolutionerande tillvägagångssätt som använder kobolt och metanol för att producera ett epilepsimedicin som tidigare krävde rodium och diklormetan, ett giftigt lösningsmedel. Deras nya reaktion fungerar snabbare och billigare, och det har sannolikt en mycket mindre miljöpåverkan, sa Chirik, Edwards S. Sanford professor i kemi. "Detta belyser en viktig princip inom grön kemi - att den mer miljömässiga lösningen också kan vara den föredragna kemiskt, "sa han. Forskningen publicerades i tidskriften Vetenskap den 25 maj.

"Farmaceutisk upptäckt och process involverar alla slags exotiska element, "Sa Chirik." Vi startade det här programmet för kanske tio år sedan, och det motiverades verkligen av kostnaden. Metaller som rodium och platina är riktigt dyra, men när arbetet har utvecklats, vi insåg att det finns mycket mer än bara prissättning. ... det finns stora miljöhänsyn, om du funderar på att gräva upp platina ur marken. Vanligtvis, du måste gå ungefär en mil djup och flytta 10 ton jord. Det har ett massivt koldioxidavtryck. "

Chirik och hans forskargrupp samarbetade med kemister från Merck &Co., Inc., att hitta mer miljövänliga sätt att skapa de material som behövs för modern läkemedelskemi. Samarbetet har möjliggjorts av National Science Foundation's Grant Opportunities for Academic Liaison with Industry (GOALI) -program.

En knepig aspekt är att många molekyler har höger- och vänsterhänta former som reagerar olika, med ibland farliga konsekvenser. Food and Drug Administration har strikta krav för att se till att mediciner bara har en "hand" åt gången, känd som enkel-enantiomerläkemedel.

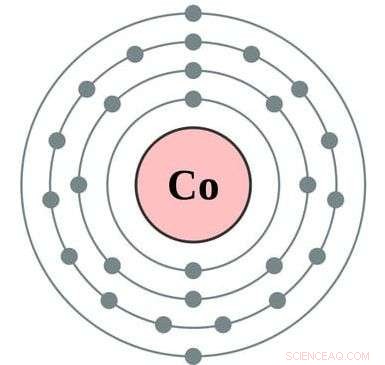

"Kemister utmanas att upptäcka metoder för att syntetisera endast en hand av läkemedelsmolekyler snarare än att syntetisera båda och sedan separera, "sa Chirik." Metallkatalysatorer, historiskt baserat på ädelmetaller som rodium, har fått i uppgift att lösa denna utmaning. Vårt papper visar att en mer jordfylld metall, kobolt, kan användas för att syntetisera epilepsimedicin Keppra som bara en hand. "

Fem år sedan, forskare i Chiriks laboratorium visade att kobolt skulle kunna göra en-enantiomer organiska molekyler, men endast med relativt enkla och inte medicinskt aktiva föreningar - och med hjälp av giftiga lösningsmedel.

"Vi inspirerades att driva vår demonstration av princip till exempel i verkligheten och visa att kobolt kan överträffa ädelmetaller och arbeta under mer miljökompatibla förhållanden, "sa han. De fann att deras nya koboltbaserade teknik är snabbare och mer selektiv än den patenterade rodiummetoden.

"Vårt papper visar ett sällsynt fall där en överflödig metall på jorden kan överträffa en ädelmetalls prestanda vid syntesen av en-enantiomerläkemedel, "sa han." Det vi börjar övergå till är att de jordartade katalysatorerna inte bara ersätter ädelmetallkatalysatorerna, men de erbjuder tydliga fördelar, oavsett om det är ny kemi som ingen någonsin sett tidigare eller om det är förbättrad reaktivitet eller minskat miljöavtryck. "

Basmetaller är inte bara billigare och mycket miljövänligare än sällsynta metaller, men den nya tekniken fungerar i metanol, which is much greener than the chlorinated solvents that rhodium requires.

"The manufacture of drug molecules, because of their complexity, is one of the most wasteful processes in the chemical industry, " said Chirik. "The majority of the waste generated is from the solvent used to conduct the reaction. The patented route to the drug relies on dichloromethane, one of the least environmentally friendly organic solvents. Our work demonstrates that Earth-abundant catalysts not only operate in methanol, a green solvent, but also perform optimally in this medium.

"This is a transformative breakthrough for Earth-abundant metal catalysts, as these historically have not been as robust as precious metals. Our work demonstrates that both the metal and the solvent medium can be more environmentally compatible."

Methanol is a common solvent for one-handed chemistry using precious metals, but this is the first time it has been shown to be useful in a cobalt system, noted Max Friedfeld, the first author on the paper and a former graduate student in Chirik's lab.

Cobalt's affinity for green solvents came as a surprise, said Chirik. "For a decade, catalysts based on Earth-abundant metals like iron and cobalt required very dry and pure conditions, meaning the catalysts themselves were very fragile. By operating in methanol, not only is the environmental profile of the reaction improved, but the catalysts are much easier to use and handle. This means that cobalt should be able to compete or even outperform precious metals in many applications that extend beyond hydrogenation."

The collaboration with Merck was key to making these discoveries, noted the researchers.

Chirik said:"This is a great example of an academic-industrial collaboration and highlights how the very fundamental—how do electrons flow differently in cobalt versus rhodium?—can inform the applied—how to make an important medicine in a more sustainable way. I think it is safe to say that we would not have discovered this breakthrough had the two groups at Merck and Princeton acted on their own."

The key was volume, said Michael Shevlin, an associate principal scientist at the Catalysis Laboratory in the Department of Process Research &Development at Merck &Co., Inc., and a co-author on the paper.

"Instead of trying just a few experiments to test a hypothesis, we can quickly set up large arrays of experiments that cover orders of magnitude more chemical space, " Shevlin said. "The synergy is tremendous; scientists like Max Friedfeld and [co-author and graduate student] Aaron Zhong can conduct hundreds of experiments in our lab, and then take the most interesting results back to Princeton to study in detail. What they learn there then informs the next round of experimentation here."

Chirik's lab focuses on "homogenous catalysis, " the term for reactions using materials that have been dissolved in industrial solvents.

"Homogenous catalysis is usually the realm of these precious metals, the ones at the bottom of the periodic table, " Chirik said. "Because of their position on the periodic table, they tend to go by very predictable electron changes—two at a time—and that's why you can make jewelry out of these elements, because they don't oxidize, they don't interact with oxygen. So when you go to the Earth-abundant elements, usually the ones on the first row of the periodic table, the electronic structure—how the electrons move in the element—changes, and so you start getting one-electron chemistry, and that's why you see things like rust for these elements.

Chirik's approach proposes a radical shift for the whole field, said Vy Dong, a chemistry professor at the University of California-Irvine who was not involved in the research. "Traditional chemistry happens through what they call two-electron oxidations, and Paul's happens through one-electron oxidation, " she said. "That doesn't sound like a big difference, but that's a dramatic difference for a chemist. That's what we care about—how things work at the level of electrons and atoms. When you're talking about a pathway that happens via half of the electrons that you'd normally expect, it's a big deal. ... That's why this work is really exciting. You can imagine, once we break free from that mold, you can start to apply it to other things, för."

"We're working in an area of the periodic table where people haven't, under en lång tid, so there's a huge wealth of new fundamental chemistry, " said Chirik. "By learning how to control this electron flow, the world is open to us."