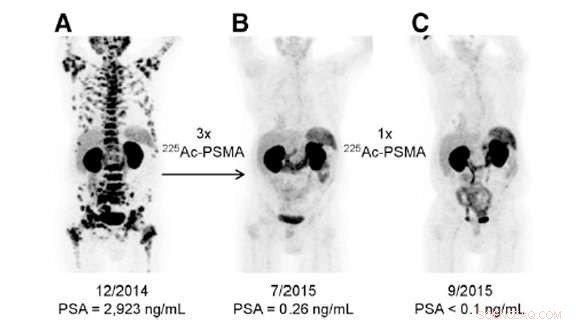

Den här bilden visar tre olika bilder av en enda patient med prostatacancer i slutstadiet. Den första togs före behandling med aktinium-225, den andra efter tre doser, och den tredje efter ytterligare en dos. Behandlingen, gjort på universitetssjukhuset Heidelberg, var extremt framgångsrik. Kredit:US Department of Energy

Inuti ett smalt glasrör sitter ett ämne som kan skada eller bota, beroende på hur du använder den. Den avger ett svagt blått sken, ett tecken på dess radioaktivitet. Medan energin och subatomära partiklar den avger kan skada mänskliga celler, de kan också döda några av våra mest envisa cancerformer. Detta ämne är aktinium-225.

Lyckligtvis, forskare har kommit på hur man kan utnyttja aktinium-225s kraft för gott. De kan fästa den på molekyler som bara kan fånga cancerceller. I kliniska prövningar som behandlar patienter med prostatacancer i sent skede, actinium-225 utplånade cancern i tre behandlingar.

"Det finns ingen återstående påverkan av prostatacancer. Det är anmärkningsvärt, sa Kevin John, en forskare vid Institutionen för energi (DOE) Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). Actinium-225 och behandlingar som härrör från det har också använts i tidiga försök för leukemi, melanom, och gliom.

Men något stod i vägen för att utöka denna behandling.

I årtionden, en plats i världen har producerat majoriteten av aktinium-225:DOE:s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). Även med två andra internationella anläggningar som bidrar med mindre belopp, alla tre tillsammans kan bara skapa tillräckligt med aktinium-225 för att behandla färre än 100 patienter årligen. Det räcker inte för att köra något annat än de mest preliminära kliniska prövningarna.

För att uppfylla sitt uppdrag att producera isotoper som är en bristvara, DOE Office of Sciences isotopprogram leder ansträngningar för att hitta nya sätt att producera aktinium-225. Genom DOE Isotope-programmets Tri-Lab forskningsansträngning för att tillhandahålla acceleratorproducerad 225Ac för strålterapiprojekt, ORNL, LANL, och DOE:s Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) har utvecklat en ny, extremt lovande process för att producera denna isotop.

Bygger på ett arv från atomåldern

Att producera isotoper för medicinsk och annan forskning är inget nytt för DOE. Isotopprogrammets ursprung går tillbaka till 1946, som en del av president Trumans försök att utveckla fredliga tillämpningar av atomenergi. Sedan dess, Atomic Energy Commission (DOE:s föregångare) och DOE har tillverkat isotoper för forskning och industriell användning. De unika utmaningarna som följer med isotopproduktion gör DOE väl lämpad för denna uppgift.

Isotoper är olika former av de vanliga atomelementen. Medan alla former av ett element har samma antal protoner, isotoper varierar i antalet neutroner. Vissa isotoper är stabila, men de flesta är det inte. Instabila isotoper sönderfaller ständigt, sänder ut subatomära partiklar som radioaktivitet. När de släpper ut partiklar, isotoper förändras till olika isotoper eller till och med olika element. Komplexiteten i att producera och hantera dessa radioaktiva isotoper kräver expertis och specialutrustning.

DOE Isotope Program fokuserar på tillverkning och distribution av isotoper som är en bristvara och stor efterfrågan, underhålla infrastrukturen för att göra det, och bedriva forskning för att producera isotoper. Den tillverkar isotoper som privata företag inte gör kommersiellt tillgängliga.

En exceptionell cancerkämpe

Att producera aktinium-225 för de nationella laboratoriernas expertis in i en ny värld.

Actinium-225 har ett sådant löfte eftersom det är en alfasändare. Alfa-sändare släpper ut alfapartiklar, som är två protoner och två neutroner bundna tillsammans. När alfapartiklar lämnar en atom, de avsätter energi längs sin korta väg. Denna energi är så hög att den kan bryta bindningar i DNA. Denna skada kan förstöra cancercellers förmåga att reparera och föröka sig, även döda tumörer.

"Alfasändare kan fungera i fall där inget annat fungerar, " sa Ekaterina (Kate) Dadachova, en forskare vid University of Saskatchewan College of Pharmacy and Nutrition som testade actinium-225 producerat av DOE.

Dock, utan ett sätt att rikta in sig på cancerceller, alfasändare skulle vara lika skadliga för friska celler. Forskare fäster alfasändare till ett protein eller en antikropp som exakt matchar receptorerna på cancerceller, som att montera ett lås i en nyckel. Som ett resultat, alfasändaren ackumuleras bara på cancercellerna, där den avger sina destruktiva partiklar på mycket kort avstånd.

"Om molekylen är korrekt designad och går till själva målet, du dödar bara cellerna som finns runt målcellen. Du dödar inte cellerna som är friska, sa Saed Mirzadeh, en ORNL-forskare som påbörjade den första ansträngningen att producera aktinium-225 vid ORNL.

Actinium-225 är unik bland alfasändare eftersom den bara har en halveringstid på 10 dagar. (En isotops halveringstid är hur lång tid det tar att sönderfalla till hälften av dess ursprungliga mängd.) På mindre än två veckor, hälften av dess atomer har förvandlats till olika isotoper. Varken för lång eller för kort, 10 days is just right for some cancer treatments. The relatively short half-life limits how much it accumulates in people's bodies. På samma gång, it gives doctors enough time to prepare, administer, and wait for the drug to reach the cancer cells in patients' bodies before it acts.

Repurposing Isotopes for Medicine

While it took decades for medical researchers to figure out the chemistry of targeting cancer with actinium-225, the supply itself now holds research back. Under 2013, the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first drug based on alpha emitters. If the FDA approves multiple drugs based on actinium-225 and its daughter isotope, bismuth-213, demand for actinium-225 could rise to more than 50, 000 millicuries (mCi, a unit of measurement for radioactive isotopes) a year. The current process can only create two to four percent of that amount annually.

"Having a short supply means that much less science gets done, " said David Scheinberg, a Sloan Kettering Institute researcher who is also an inventor of technology related to the use of actinium-225. (This technology has been licensed by the Sloan Kettering Institute at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to Actinium Pharmaceuticals, for which Scheinberg is a consultant.)

Part of this scarcity is because actinium is remarkably rare. Actinium-225 does not occur naturally at all.

Scientists only know about actinium-225's exceptional properties because of a quirk of history. På 1960-talet scientists at the DOE's Hanford Site produced uranium-233 as a fuel for nuclear weapons and reactors. They shipped some of the uranium-233 production targets to ORNL for processing. Those targets also contained thorium-229, which decays into actinium-225. 1994, a team from ORNL led by Mirzadeh started extracting thorium-229 from the target material. They eventually established a thorium "cow, " from which they could regularly "milk" actinium-225. In August 1997, they made their first shipment of actinium-225 to the National Cancer Institute.

För närvarande, scientists at ORNL "milk" the thorium-229 cow six to eight times a year. They use a technique that separates out ions based on their charges. Tyvärr, the small amount of thorium-229 limits how much actinium-225 scientists can produce.

Accelerating Actinium-225 Research

I sista hand, the Tri-Lab project team needed to look beyond ORNL's radioactive cow to produce more of this luminous substance.

"The route that looked the most promising was using high-energy accelerators to irradiate natural thorium, " said Cathy Cutler, the director of BNL's medical isotope research and production program.

Only a few accelerators in the country create high enough energy proton beams to generate actinium-225. BNL's Linear Accelerator and LANL's Neutron Science Center are two of them. While both mainly focus on other nuclear research, they create plenty of excess protons for producing isotopes.

The new actinium-225 production process starts with a target made of thorium that's the size of a hockey puck. Scientists place the target in the path of their beam, which shoots protons at about 40 percent the speed of light. As the protons from the beam hit thorium nuclei, they raise the energy of the protons and neutrons in the nuclei. The protons and neutrons that gain enough kinetic energy escape the thorium atom. Dessutom, some of the excited nuclei split in half. The process of expelling protons and neutrons as well as splitting transforms the thorium atoms into hundreds of different isotopes – of which actinium-225 is one.

After 10 days of proton bombardment, scientists remove the target. They let the target rest so that the short-lived radioisotopes can decay, reducing radioactivity. They then remove it from its initial packaging, analysera det, and repackage it for shipping.

Then it's off to ORNL. Scientists there receive the targets in special containers and transfer them to a "hot cell" that allows them to work with highly radioactive materials. They separate actinium-225 from the other materials using a similar technique to the one they use to produce "milk" from their thorium cow. They determine which isotopes are in the final product by measuring the isotopes' radioactivity and masses.

Trials and Tribulations

Figuring out this new process was far from easy.

Först, the team had to ensure the target would hold up under the barrage of protons. The beams are so strong they can melt thorium – which has a melting point above 3, 000 degrees F. Scientists also wanted to make it as easy as possible to separate the actinium-225 from the target later on.

"There's a lot of work that goes into designing that target. It's really not a simple task at all, " said Cutler.

Nästa, the Tri-Lab team needed to set the beamlines to the right parameters. The amount of energy in the beam determines which isotopes it produces. By modeling the process and then conducting trial-and-error tests, they determined settings that would produce as much actinium-225 as possible.

But only time and testing could resolve the biggest challenge. While sorting actinium out from the soup of other isotopes was difficult, the ORNL team could do it using fairly standard chemical practices. What they can't do is separate out the actinium-225 from its longer-lived counterpart actinium-227. When the team ships the final product to customers, it has about 0.3 percent actinium-227. With a half-life of years rather than days, it could potentially remain in patients' bodies and cause damage for far longer than actinium-225 does.

To understand the consequences of the actinium-227 contamination, the Tri-Lab team collaborated with medical researchers, including Dadachova, to test the final product. After analyzing the material for purity and testing it on mice, the researchers found no significant differences between the actinium-225 produced using the ORNL and the accelerator method. The amount of actinium-227 was so miniscule that it "doesn't make any difference, " said Dadachova.

Happily Ever After?

Having resolved many of the biggest issues, the Tri-Lab project team is in the midst of working out the new process's details. They estimate they can provide more than 20 times as much actinium-225 to medical researchers as they were able to originally. Those researchers are now investigating what dosages would maximize effectiveness while minimizing the drug's toxicity. På samma gång, the national labs are pursuing upgrades to expand production to the level needed for a commercial drug. They're also working to make the entire process more efficient.

"Having a larger supply from the DOE is essential to expanding the trials to more and more centers, " said Scheinberg. With the Tri-Lab project ahead of schedule, it appears that the new production process for actinium-225 could lead to a better ending for more patients than ever before.