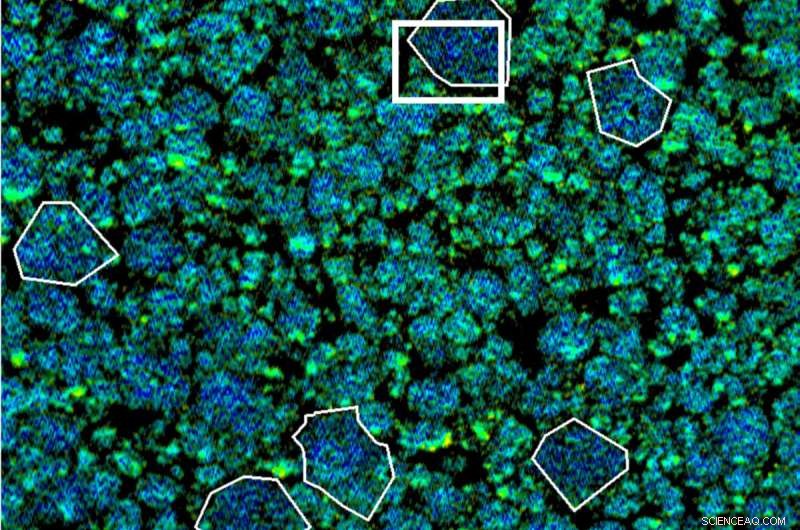

Detaljerade röntgenmätningar vid Advanced Light Source hjälpte ett forskarlag som leds av Berkeley Lab, SLAC och Stanford University avslöja hur syre sipprar ut ur de miljarder nanopartiklar som utgör litiumjonbatteriets elektroder. Kredit:Berkeley Lab

Under en tremånadersperiod producerar den genomsnittliga bilen i USA ett metriskt ton koldioxid. Multiplicera det med alla bensindrivna bilar på jorden, och hur ser det ut? Ett oöverstigligt problem.

Men nya forskningsinsatser säger att det finns hopp om vi förbinder oss till nettonoll koldioxidutsläpp till 2050, och ersätter gasslukande fordon med elfordon, bland många andra lösningar för ren energi.

För att hjälpa vår nation att nå detta mål arbetar forskare som William Chueh och David Shapiro tillsammans för att ta fram nya strategier för att designa säkrare långdistansbatterier gjorda av hållbara material som innehåller mycket jord.

Chueh är docent i materialvetenskap och teknik vid Stanford University som syftar till att designa om det moderna batteriet från botten och upp. Han förlitar sig på toppmoderna verktyg vid U.S. Department of Energys vetenskapliga användaranläggningar som Berkeley Labs avancerade ljuskälla (ALS) och SLAC:s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source – synkrotronanläggningar som genererar ljusa strålar av röntgenljus – för att avslöja den molekylära dynamiken hos batterimaterial i arbete.

I nästan ett decennium har Chueh samarbetat med Shapiro, en senior forskare vid ALS och en ledande synkrotronexpert – och tillsammans har deras arbete resulterat i fantastiska nya tekniker som för första gången avslöjar hur batterimaterial fungerar i aktion, i realtid , i oöverträffade skalor osynliga för blotta ögat.

De diskuterar sitt banbrytande arbete i denna Q&A.

F:Vad fick dig att intressera dig för forskning om batteri/energilagring?

Chueh:Mitt arbete drivs nästan helt av hållbarhet. Jag engagerade mig i energimaterialforskning när jag var doktorand i början av 2000-talet – jag arbetade med bränslecellsteknik. När jag började på Stanford 2012 blev det uppenbart för mig att skalbar och effektiv energilagring är avgörande.

Idag är jag mycket glad över att se att energiomställningen bort från fossila bränslen nu blir verklighet och att den implementeras i otrolig skala.

Jag har tre mål:För det första gör jag grundforskning som lägger grunden för att möjliggöra energiomställningen, särskilt när det gäller materialutveckling. För det andra utbildar jag forskare och ingenjörer i världsklass som kommer att gå ut i den verkliga världen för att lösa dessa problem. Och sedan för det tredje, jag tar den grundläggande vetenskapen och översätter den till praktisk användning genom entreprenörskap och tekniköverföring.

Så förhoppningsvis ger det dig en heltäckande bild av vad som driver mig och vad jag tror att det krävs för att göra skillnad:det är kunskapen, människorna och tekniken.

Shapiro:Min bakgrund är inom optik och koherent röntgenspridning, så när jag först började arbeta på ALS 2012 var batterierna inte riktigt på min radar. Jag fick i uppdrag att utveckla ny teknik för röntgenmikroskopi med hög rumslig upplösning, men detta ledde snabbt till tillämpningarna och försökte ta reda på vad forskare vid Berkeley Lab och vidare gör och vad deras behov är.

Vid den tiden, runt 2013, var det mycket arbete vid ALS med olika tekniker som utnyttjade den kemiska känsligheten hos mjuka röntgenstrålar för att studera fasomvandlingar i batterimaterial, i synnerhet litiumjärnfosfat (LiFePO4) bland annat.

Jag var verkligen imponerad av Wills arbete såväl som av Wanli Yang, Jordi Cabana (en tidigare anställd forskare i Berkeley Labs Energy Technologies Area (ETA) som nu är docent vid University of Illinois Chicago), och andra vars arbete också byggde off of work av ETA-forskarna Robert Kostecki och Marca Doeff.

I knew nothing about batteries at the time, but the scientific and social impact of this area of research quickly became apparent to me. The synergy of research across Berkeley Lab also struck me as very profound, and I wanted to figure out how to contribute to that. So I started to reach out to people to see what we could do together.

As it turned out, there was a great need to improve the spatial resolution of our battery materials measurements and to look at them during cycling—and Will and I have been working on that for nearly a decade now.

Q:Will, as a battery scientist, what would you say is the biggest challenge to making better batteries?

Chueh:Batteries have on the order of 10 metrics that you have to co-optimize at the same time. It's easy to make a battery that's good on maybe five out of the 10, but to make a battery that's good in every metric is very immensely challenging.

For example, let's say you want a battery that is energy dense so you can drive an electric car for 500 miles per charge. You may want a battery that charges in 10 minutes. And you may want a battery that lasts 20 years. You also want a battery that never explodes. But it's hard to meet all of these metrics at once.

What we're trying to do is understand how we can create a single battery technology that is safe, long-lasting, and can be charged in 10 minutes.

And those are the fundamental insights that our experiments at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source are trying to do:To uncover those unexplained tradeoffs so that we can go beyond today's design rules, which would enable us to identify new materials and new mechanisms so that we can free ourselves from those restrictions.

Q:What unique capabilities does the ALS offer that have helped to push the boundaries of battery or energy storage research?

Chueh:In order to understand what's going on, we need to see it. We need to make observations. A key philosophy of my group is to embrace the dynamics and the heterogeneity of battery materials. A battery material is not like a rock. It's not static. You are charging and discharging it every day for your phones and every week for your electric cars. You're not going to understand how a car works by not driving it.

The second part is that heterogeneous battery materials are extremely length spanning. A battery cell is typically a few centimeters tall, but in order to understand what's going on inside the battery—and I have beautiful images for this—you want to see all the way down to the nanoscale and to the atomic scale. That's about 10 orders of magnitude of length.

What the Advanced Light Source empowers scientists like me to be able to do is to embrace the heterogeneity and dynamics of a battery in very unprecedented ways:We can measure very slow processes. We can measure very fast processes. We can measure things at the scale of many hundreds of microns (millionths of a meter). We can measure things at the nanoscale (billionth of a meter). All with one amazing tool at Berkeley Lab.

Shapiro:Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) is a very popular synchrotron-based method. Most synchrotrons around the world have at least one STXM instrument while the ALS has three—and a fourth is on the way through the ALS Upgrade (ALS-U) project.

I think a few things make our program unique. First, we have a portfolio of instruments with specializations. One is optimized for light element spectroscopy so an element like oxygen, which is a critical ingredient in battery chemistry, can be precisely characterized.

Another instrument specializes in mapping chemical composition at very high spatial resolution. We have the highest spatial resolution X-ray microscopy in the world. This is very powerful for zooming in on the chemical reactions happening within a battery's individual nanoparticles and interfaces.

Our third instrument specializes in "operando" measurements of battery chemistry, which you need in order to really understand the physical and chemical evolution that occurs during battery cycling.

We have also worked hard to develop synergies with other facilities at Berkeley Lab. For instance, our high-resolution microscope uses the same sample environments as the electron microscopes at the Molecular Foundry, Berkeley Lab's nanoscience user facility—so it has become feasible to probe the same active battery environment with both X-rays and electrons. Will has used this correlative approach to study relationships between chemical states and structural strain in battery materials. This has never been done before at the length scales we have access to, and it provides new insight.

Q:How will the ALS Upgrade project advance next-gen energy storage technologies? What will the upgraded ALS offer battery/energy-storage researchers that will be unique to Berkeley Lab?

Shapiro:The upgraded ALS will be unique for a few reasons as far as microscopy is concerned. First, it will be the brightest soft X-ray source in the world, providing 100 times more X-rays on th sample than what we have today. Scanning microscopy techniques will benefit from such high brightness.

This is both a huge opportunity and a huge challenge. We can use this brightness to measure the data we get today—but doing this 100 times faster is the challenging part.

Such new capabilities will give us a much more statistically accurate look at battery structure and function by expanding to larger length scales and smaller time scales. Alternatively, we could also measure data at the same rate as today but with about three times finer spatial resolution, taking us from about 10 nanometers to just a few nanometers. This is a very important length scale for materials science, but today it's just not accessible by X-ray microscopy.

Another thing that will make the upgraded ALS unique is its proximity to expertise at the Molecular Foundry; other science areas such as the Energy Technologies Area; and current and future energy research hubs based at Berkeley Lab. This synergy will continue to drive energy storage research.

Chueh:In battery research, one of the challenges we have right now is that we have so many interesting problems to solve, but it takes hours and days to do just one measurement. The ALS-U project will increase the throughput of experiments and allow us to probe materials at higher resolution and smaller scales. Altogether, that adds up to enabling new science. Years ago, I contributed to making the case for ALS-U, so I couldn't be prouder to be part of that—I'm very excited to see the upgraded ALS come online so we can take advantage of its exciting new capabilities to do science that we cannot do today.