Att avslöja kostnader, risker och möjligheter – NREL-forskare, inklusive vetenskapsmannen Zhe Huang (bilden), analyserar den tekniska och ekonomiska potentialen för att elektrifiera – och dekarbonisera – bränsle- och kemikalieproduktion. Kredit:Werner Slocum, NREL

Petroleum, kol och naturgas är inte de enda utgångspunkterna för att tillverka bränslen och kemikalier. Faktum är att växande utbud av förnybar el öppnar nya spännande dörrar för att tillverka identiska produkter till potentiellt en bråkdel av klimatkostnaden.

Det börjar med att ett vindturbin eller en solpanel stadigt vänder sig bak i mitten av eftermiddagssolen. En ström flyter genom en elektrokemisk cell fylld med koldioxid (CO2). )—hävert från luften eller fångat från ett etanolraffinaderi, cementfabrik eller annan industriell källa.

Kolatomen i gasen, som drivs av joner och radikaler som skapas av laddningen, lossnar sig från sina syregrannar och letar efter nya följeslagare att binda till. Det låser sig snabbt till annat nyligen frigjort kol, såväl som väteatomer som genereras i cellen.

Den exakta molekylen kolet hjälper till att bilda beror på elektrokatalysatorn i cellen och spänningen som applicerades i början:

Det är en elektrokemisk reaktion, en framväxande väg för att uppgradera CO2 och till och med biomassahärledda föreningar till de många plaster, tvättmedel, bränslen och föreningar som ligger bakom den moderna ekonomin.

Tillsammans med en bredare uppsättning tekniker som använder förnybar el för att syntetisera kemikalier och bränslen, har teknologin ett löfte om att hjälpa till att minska koldioxidutsläppen från den tunga industrin. Men är de verkligen redo för marknaden?

Om kostnaderna, riskerna och möjligheterna med att elektrifiera kemikalier och bränsleproduktion

"I huvudsak talar vi om en skärningspunkt mellan elektrifiering och utnyttjande av råvaror med låg koldioxidhalt som koldioxid och biomassa", säger Joshua Schaidle, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) programansvarig för det amerikanska energidepartementets kontor för fossil energi och Koldioxidhantering. Schaidle leder också NREL:s forskning om katalytisk kolomvandling och leder U.S. Department of Energys Chemical Catalysis for Bioenergy Consortium. "Drivna av förnybar energi istället för fossilbaserad el, kan dessa system tillåta industrier att gå bortom fossilt kol."

Enligt Schaidle och hans NREL-kollega Gary Grim kan den alternativa metoden för att tillverka bränslen och kemikalier vara ett avgörande verktyg för att minska koldioxidutsläppen i en ekonomisk sektor som ofta lämnar djupa koldioxidavtryck i sitt spår.

Istället för att muddra upp "fossilt" kol som lagrats under jord, återvinner sådana metoder "modernt" kol som finns i CO2 eller biomassa. Och snarare än att förlita sig på kolintensiva energikällor, drivs de av förnybar el med nollutsläpp. Resultatet kan bli en bränsle- och kemikalieproduktionsprocess som är betydligt mindre kolintensiv.

Ändå kvarstår många frågor om kostnaderna, riskerna och tekniska utmaningarna med att tillverka kemikalier och bränslen från grön el och återvunnet kol. "Var finns teknologierna i dag? Var kan de vara i framtiden? Och hur spelar det en roll i nästa steg och framtida forskningsbehov?" frågade Schaidle.

I ett par artiklar publicerade i Energy and Environmental Science och ACS Energy Letters, Schaidle, Grim och kollegor utforskar dessa frågor och andra om den tekniska och ekonomiska potentialen i att elektrifiera – och koldioxidutsläppa – bränsle- och kemikalieproduktion.

Med mycket osäkerhet kvar hoppas de att ett sådant arbete kan hjälpa till att markera vägen framåt från labbbordet till den kommersiella världen.

Papper 1:Ekonomin för koldioxidutnyttjande

Studier tyder på att det finns teknik idag för att omvandla CO2 in i alla de mest globalt konsumerade kolbaserade kemikalierna och produkterna – en marknad som för närvarande domineras av fossila kolkällor.

Genom ett onlinevisualiseringsverktyg ger NREL insikt i den ekonomiska genomförbarheten och de viktigaste kostnadsdrivkrafterna för att producera kemiska intermediärer från CO2 och elektricitet över fem olika omvandlingsvägar. Dessa inkluderar vägar som använder förnybar el direkt för att kemiskt uppgradera CO2 till kemikalier, samt vägar som använder el indirekt via mellanliggande elektronbärare, som väte. Kredit:Werner Slocum, NREL

Till exempel, varje år släpps över 10 gigaton koldioxid ut som CO2 runt världen. Om den fångas och skickas genom en elektrokemisk cell istället, kommer den CO2 kan bli en råvara – en tillräckligt stor för att producera över 40 gånger hela den globala produktionen av eten och propen.

I en Energi- och miljövetenskap paper, "The Economic Outlook for Converting CO2 and Electrons to Molecules," NREL-forskare Zhe Huang, Schaidle, Grim och Ling Tao analyserar ekonomin för elektrokemisk CO2 utnyttjande idag och i framtiden. Uppsatsen tar hänsyn till många teknikfaktorer och kostnadsdrivande faktorer som kan påverka möjligheten att producera kemikalier, bränslen och material från CO2 och förnybar el i stor skala.

"Vi tar en bred titt över flera tekniker till flera produkter," sa Grim. "Nyckelpunkten är att vi använder konsekventa ekonomiska antaganden för vår analys."

Enligt deras studie kan det snart vara lika kostnadseffektivt att göra några av de mest använda kemikalierna av CO2 och grön el som det är för att göra dem med nuvarande petroleumbaserade metoder. Med den nuvarande takten med fallande elpriser och förväntade teknikförbättringar kan det i vissa fall till och med bli billigare.

"De framsteg vi ser, aktiviteten vi ser - vi kommer att ha kommersiella erbjudanden under de kommande 5 till 10 åren," sa Schaidle. "I think there are opportunities to get down to cost competitiveness, especially as you start to consider any low-carbon credits that come along."

To arrive at such conclusions, the study incorporates a broad range of assumptions. It considers energy prices and the cost to build new facilities or install new equipment. It factors in technical and chemical influences that could impact the viability of a technology, such as the speed or efficiency of a certain electrochemical reaction.

Not least, the analysis takes a close look at the impact of CO2 source and concentration on the price to make a given chemical, be it carbon monoxide, ethylene, or a hydrocarbon fuel. Where CO2 siphoned directly from the atmosphere is relatively dilute, for example, capturing it from a power plant or biorefinery yields higher concentrations.

To make it easier to sift through the data behind their analysis, Schaidle, Grim, and their colleagues have published a powerful online visualization tool. It includes interactive charts on the economic feasibility and key cost drivers of producing chemical intermediates from CO2 and electricity across five different conversion pathways.

In this way, the takeaways from the paper become easily accessible for a broad audience. For example, their analysis concludes that carbon monoxide made from CO2 and electricity via high-temperature electrolysis—a specific kind of electrochemical technology—would be relatively expensive by today's standards, at $0.38 per kilogram. Move into the near future, however, and the economics flip. The study projects the price to fall well below today's market price to $0.15 per kilogram.

"Is this a reality? How close can we get on a cost-competitive basis?" reflected Schaidle. "What are the performers or non-performers?"

With the new paper and visualization tool, arriving at answers is easier than ever before.

Paper 2:The status of electrochemical conversion of plentiful biomass

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, biomass resources in the United States could be harnessed to produce up to 50 billion gallons of biofuel each year, more than enough to cover the entire U.S. demand for jet fuel.

But where the carbon in CO2 forms a simple chemical configuration—a gas with one part carbon, two parts oxygen—the renewable carbon in that plentiful biomass is integrated into fibrous networks of lignin and carbohydrates. That makes the starting point for making chemicals with biomass fundamentally different.

Biomass—which includes energy crops, forestry waste, and other organic matter—must first be broken apart into chemical intermediates:polyols, furans, carboxylic acids, amino acids, lignin, and others. Once stored in a more basic form, that renewable carbon can then be more easily accessed, amended, and rearranged.

"You can convert these intermediate molecules thermochemically and biologically, but you can also look at electrochemistry," Schaidle explained. "Our review focuses on the latter piece, where you are looking at converting an intermediate into a product rather than starting with whole biomass."

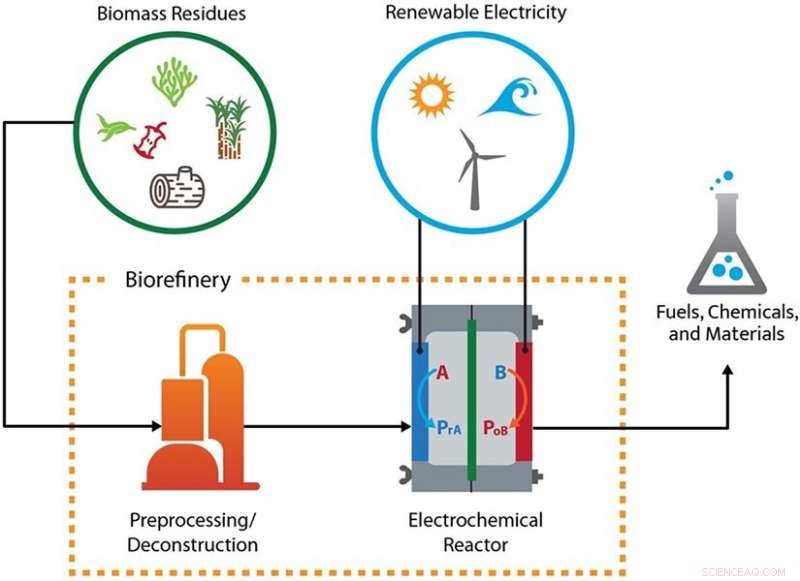

A large number of fuels, chemicals, and materials can be accessed from biomass using renewable electricity. In the electrochemical reactor, “A” and “B” represent biomass-derived compounds that are upgraded by forming either reduction products (blue arrow, PrA) or oxidation products (red arrow, PoB). Credit:National Renewable Energy Laboratory

In a second paper published in ACS Energy Letters , Schaidle, Grim, and a larger team of scientists—including Francisco W.S. Lucas and Adam Holewinski from the University of Colorado, Boulder—analyze over 82 reactions driven by the electrochemical synthesis of biomass intermediates. Those reactions have potential advantages, according to the paper.

"Conventional methods only have heat and pressure as their hammers," Grim explained. "With electrochemistry and biomass intermediates, we have the ability to target specific chemical bonds or groups that can be otherwise difficult to access."

Grim said that could give industries more latitude to invent chemistries otherwise hard to achieve—a potential advantage over conventional, petroleum-based refining. Still, the electrochemical synthesis of biomass intermediates is immature compared to CO2 utilization.

"If you want this technology to get closer to becoming market competitive, you have to have an electrochemical process that is overall more efficient," Schaidle added. "It makes the best utilization of the carbon coming in and the best utilization of the electrons coming in. That is where a lot of the technology advancements need to happen."

By pulling together more than 500 publications on the field—articles often focused on specific reactions using electrochemistry—the paper serves as a roadmap for assessing the state of electrochemistry with biomass-derived intermediates and finding the best entry points for improving the technology. With this broad analysis, the team of scientists aims to foster more focus and intentionality in future research.

"This is cross-cutting analysis to help people move forward," Schaidle added. "We are synthesizing all the science to give a clear blueprint for strategic research."

Slow but steady:Steps to decarbonizing chemical manufacturing

Schaidle and Grim are honest about the challenges ahead. After all, should we even try to electrify biomass conversion? Why convert CO2 and not just capture it and put it underground?

"The short answer is that there are a lot of challenges," Grim said. "Petroleum- and fossil-based processes have had nearly a century head-start on some of these emerging technologies. Those systems are highly optimized, very well studied—and hydrocarbons have a lot of energy already built in."

With no energy content whatsoever, CO2 must be pumped with massive amounts of cheap, clean energy to successfully transform it into something usable. Many electrochemical technologies for converting biomass intermediates have yet to be scaled beyond the lab—an essential step for demonstrating the stability, efficiency, and affordability of any bioenergy technology. Not least, robust supply chains of renewable electrons, CO2 , and biomass are only just emerging.

"The jury is still out:Is this the best use of that abundant future electricity?" Grim asked. "We are still working to understand if these technologies are the best solution for addressing a lot of our climate issues."

Despite the challenges, Schaidle and Grim remain optimistic that these technologies can play a critical role in decarbonizing fuel and chemical manufacturing.

Supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Bioenergy Technologies Office, ARPA-E, and other energy programs, a range of targeted research projects are already helping push down the cost and increase the efficacy of such technologies. One NREL-led team, for instance, is exploring how to use electrochemistry to enable biorefineries to recycle waste CO2 —increasing fuel yields by as much as 40% and decarbonizing the production of ethanol, as well as lipids.

With a nudge in the right direction, more breakthrough projects could be on the horizon.

"How do we guide this field to collectively accelerate everyone's work?" Schaidle said. "That's what we wanted to do—to take this blob of an amoeba and turn it into a foundational first step for people to build off of."

By gathering all the available data—standardizing it, making it comprehensible, giving it form—they hope they can collapse the timeline for improving the technologies. And with deadlines looming for making meaningful progress to lower climate-warming emissions, accelerating R&D could be just what is needed to start eliminating the weighty carbon footprint of making fuels and chemicals.