Stå bra tillbaka. Kredit:RHJPhtotoandilustration

Det är ett år sedan Horizon Nuclear Power, ett företag som ägs av Hitachi, bekräftade att det skulle dra sig ur byggandet av Wylfa-kärnkraftverket på 20 miljarder pund i Anglesey i norra Wales. Det japanska industrikonglomeratet hänvisade till misslyckandet med att nå ett finansieringsavtal med den brittiska regeringen på grund av eskalerande kostnader, och regeringen pågår fortfarande förhandlingar med andra aktörer för att försöka ta projektet framåt.

Hitachis aktiekurs steg med 10 % när den tillkännagav sitt tillbakadragande, vilket speglar investerarnas negativa sentiment mot att bygga komplexa, högt reglerade stora kärnkraftverk. Med regeringar som är ovilliga att subventionera kärnkraft på grund av de höga kostnaderna, särskilt efter Fukushima-katastrofen 2011, har marknaden undervärderat potentialen hos denna teknik för att tackla klimatkrisen genom att tillhandahålla riklig och pålitlig el med låga koldioxidutsläpp.

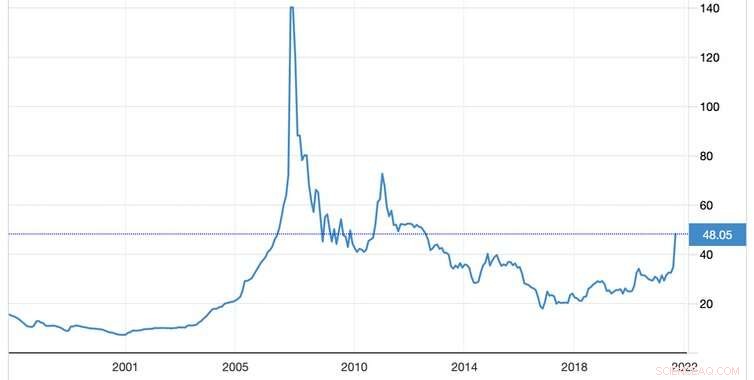

Uranpriserna återspeglade länge denna verklighet. Det primära bränslet för kärnkraftverk höll på att glida under stora delar av 2010-talet, utan tecken på en större vändning. Ändå sedan mitten av augusti har priserna stigit med cirka 60 % när investerare och spekulanter kämpar för att ta tag i råvaran. Priset är cirka 48 USD per pund (453 g), efter att ha varit så billigt som 28,99 USD den 16 augusti. Så vad ligger bakom detta rally, och vad betyder det för kärnkraften?

Uranpris

Uranmarknaden

Efterfrågan på uran är begränsad till kärnkraftsproduktion och medicinsk utrustning. Den årliga globala efterfrågan är 150 miljoner pund, med kärnkraftverk som vill säkra kontrakt ungefär två år före användning.

Även om efterfrågan på uran inte är immun mot ekonomiska nedgångar, är den mindre utsatt än andra industriella metaller och råvaror. Huvuddelen av efterfrågan är fördelad på cirka 445 kärnkraftverk som är verksamma i 32 länder, med utbudet koncentrerat till en handfull gruvor. Kazakstan är lätt den största producenten med över 40 % av produktionen, följt av Australien (13 %) och Namibia (11 %).

Eftersom det mesta av brutet uran används som bränsle i kärnkraftverk, är dess inneboende värde nära kopplat till både nuvarande efterfrågan och framtida potential från denna industri. Marknaden omfattar inte bara urankonsumenter utan även spekulanter, som köper när de tror att priset är billigt och eventuellt bjuder upp priset. En sådan långsiktig spekulant är Toronto-baserade Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, som har köpt nästan 6 miljoner pund (eller värd 240 miljoner USD) uran de senaste veckorna.

Varför investerares optimism kan öka

Även om det är allmänt ansett att kärnenergi bör spela en integrerad roll i omställningen av ren energi, har de höga kostnaderna gjort den okonkurrenskraftig jämfört med andra energikällor. Men tack vare kraftiga höjningar av energipriserna förbättras kärnkraftens konkurrenskraft. Vi ser också ett större engagemang för nya kärnkraftverk från Kina och andra håll. Meanwhile, innovative nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors (SMRs), which are being developed in countries including China, the US, UK and Poland, promise to reduce upfront capital costs.

Credit:Trading Economics

Combined with recent optimistic releases about nuclear power from the World Nuclear Association and the International Atomic Energy Agency (the IAEA upped its projections for future nuclear-power use for the first time since Fukushima) this is all making investors more bullish about future uranium demand.

The effect on the price has also been multiplied by issues on the supply side. Due to the previously low prices, uranium mines around the world have been mothballed for several years. For example, Cameco, the world's largest listed uranium company, suspended production at its McArthur River mine in Canada in 2018.

Global supply was further hit by COVID-19, with production falling by 9.2% in 2020 as mining was disrupted. At the same time, since uranium has no direct substitute, and is involved with national security, several countries including China, India and the US have amassed large stockpiles—further limiting available supply.

Hang on tight

When you compare the cost of producing electricity over the lifetime of a power station, the cost of uranium has a much smaller impact on a nuclear plant than the equivalent effect of, say, gas or biomass:it's 5% compared to around 80% in the others. As such, a big rise in the price of uranium will not massively affect the economics of nuclear power.

Yet there is certainly a risk of turbulence in this market over the months ahead. In 2021, markets for the likes of Gamestop and NFTs have become iconic examples of speculative interest and irrational exuberance—optimism driven by mania rather than a sober evaluation of the economic fundamentals.

The uranium price surge also appears to be catching the attention of transient investors. There are indications that shares in companies and funds (like Sprott) exposed to uranium are becoming meme stocks for the r/WallStreetBets community on Reddit. Irrational exuberance may not have explained the initial surge in uranium prices, but it may mean more volatility to come.

We could therefore see a bubble in the uranium market, and don't be surprised if it is followed by an over-correction to the downside. Because of the growing view that the world will need significantly more uranium for more nuclear power, this will likely incentivise increased mining and the release of existing reserves to the market. In the same way as supply issues have exacerbated the effect of heightened demand on the price, the same thing could happen in the opposite direction when more supply becomes available.

You can think of all this as symptomatic of the current stage in the uranium production cycle:a glut of reserves has suppressed prices too low to justify extensive mining, and this is being followed by a price surge which will incentivise more mining. The current rally may therefore act as a vital step to ensuring the next phase of the nuclear power industry is adequately fuelled.

Amateur traders should be careful not to get caught on the wrong side of this shift. But for a metal with a half life of 700 million years, serious investors can perhaps afford to wait it out.