En Brixham-trålare från 1800-talet av William Adolphus Knell. Kredit:National Maritime Museum/Wikipedia

De brittiska båtarna överträffades med cirka åtta till en av fransmännen. Snart inträffade kollisioner och projektiler kastades. Britterna tvingades retirera, återvänder till hamn med krossade rutor men som tur är inga skador.

Konflikten bakom denna skärmytsling mellan brittiska och franska fiskare i Seinebukten i slutet av augusti 2018 kallades snabbt "kammusmusslakriget" i pressen. Fransmännen hade försökt hindra de brittiska mudderverken från att lagligt fiska bäddarna i franska nationella vatten. Men händelsen avslöjade spänningar som har puttrat i många år.

Enligt Europeiska unionens gemensamma fiskeripolitik (CFP), de brittiska fiskarna hade laglig rätt att fiska i dessa vatten, precis som alla båtar från ett EU-land. Komplikationen kom från en fransk förordning som hindrade lokala båtar från att fiska i dessa vatten mellan 16 maj och 30 september varje år, för att bestånden ska kunna återhämta sig från den årliga skörden. Men under den gemensamma fiskeripolitiken, ett EU-land har ingen befogenhet att hindra en annan medlemsstats flotta från att fiska dess vatten.

Denna egenhet i den gemensamma fiskeripolitiken gjorde att de franska fiskarna inte kunde muddra efter pilgrimsmusslor förrän den 1 oktober, och tvingades stå bredvid och titta på medan flottor från andra länder skördade vad de såg som en fransk resurs från franska vatten. När de brittiska båtarna anlände, de franska fiskarna tog på sig rollen som väktare av sin resurs, handlingar som de trodde var berättigade men av den brittiska fiskeindustrin sågs som olagliga.

Denna incident i ett litet hörn av ett delat EU-hav avgjordes inom några veckor tack vare ett nytt avtal om hur de två länderna skulle dela på pilgrimsmusslor. Men de underliggande spänningarna som den gemensamma fiskeripolitiken har skapat när det gäller att dela nationella resurser går mycket djupare, med en känsla av att reglerna inte tillåter en rättvis användning av haven.

Denna känsla av orättvisa uttrycktes uppenbarligen i den roll som fisket spelade i Storbritanniens beslut att lämna EU. Kampanjer lovade att "att ta tillbaka kontrollen" över brittiska vatten skulle göra det möjligt för landet att återuppliva sin sedan länge tillbakagångna fiskeindustri och de samhällen som är beroende av den.

Men oavsett vilken inverkan den gemensamma fiskeripolitiken har haft på Storbritanniens fiskare, deras framtid efter Brexit beror mycket på eventuella framtida handelsavtal som regeringen förhandlar fram med EU. Och historien om hur Storbritannien har reagerat på konflikter om fiskerättigheter som är mycket större än kammusslorkriget bådar inte gott för industrin.

Början på nedgången

Forskning om fiskeverksamhet visar att nedgången för den brittiska fiskeindustrin började långt innan någon europeisk fiskeripolitik skapades. Faktiskt, dess yttersta ursprung kan spåras till en överraskande källa:järnvägens utbyggnad i slutet av 1800-talet.

Trålfiske, under seglets makt, hade funnits i mer än 500 år. Men utan kylning, fisk kunde endast levereras för försäljning till områden nära hamnarna. Tillkomsten av järnvägsnätet innebar att fisk kunde transporteras inåt landet till stora städer.

För att ytterligare möta denna växande efterfrågan, ångtrålare började ersätta segeltrålare från 1880-talet och framåt. Kraften hos dessa ångfartyg ökade avsevärt omfattningen av trålning och gjorde att de kunde tråla längre och längre bort från hamnen samtidigt som de bogserade större nät. Brittiska ångtrålare vågade sig längre bort från Storbritannien på jakt efter fisk, med fiskevatten som expanderar till områden så långt som till Grönland, norra Norge och Barents hav, Island och Färöarna.

Men redan 1885 Det framfördes farhågor om att detta tekniska framsteg hade en negativ inverkan på både fiskebestånden och deras livsmiljö. Bevis från register över fiskeaktivitet visar att denna förbättring av tekniken och den ökade storleken på fiskeflottan låg bakom ökningen av landningarna.

Den fiskeboom som järnvägarna hade släppt lös visade sig ohållbar, och det resulterande överfisket skulle i slutändan föra industrin in i en långsiktig nedgång. Efter decennier av mer och mer fiske, landningarna började så småningom minska efter andra världskriget, en trend som fortsatte under andra hälften av 1900-talet och in i det nya millenniet.

Att kompensera, flottans storlek och kraft fortsatte att öka eftersom mer ansträngning krävdes för att fånga allt mindre fisk. Från slutet av 1950-talet, mängden landad fisk per kraftenhet minskade i snabbare takt än fisklandningar, eftersom flottan fortsatte att lägga ner mer och mer ansträngningar för att behålla fångsternas storlek. Dock, denna ansträngning var helt förgäves och 1980 hade fångsterna sjunkit till sin lägsta nivå på ett sekel.

Islands Odinn och HMS Scylla drabbar samman i Nordatlanten under "tredje torskkriget" på 1970-talet. Kredit:Isaac Newton/www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

Torskkrig

Överfiske var inte den enda orsaken till nedgången, dock. De fallande fiskbestånden i kombination med förbättringarna i flottans räckvidd och kraft under efterkrigsåren ledde till att Storbritanniens fiskare sökte nya vatten, med fler båtar som flyttar längre bort från Storbritannien för att fånga tillräckligt med fisk för att möta den inhemska efterfrågan. Och denna långväga trålning förde den brittiska flottan i konflikt med Island.

Brittiska fiskare hade fiskat dessa vatten från 1400-talet. Dock, Islands fiskeindustri började tycka om detta när ångtrålarna började fiska utanför Island i slutet av 1800-talet. Det ledde till anklagelser om att brittiska trålare skadade fiskeområdena och utarmade bestånden. 1952, Island deklarerade en fyramilszon runt sitt land för att stoppa överdrivet utländskt fiske, även om fisk inte håller sig till mänskliga gränser och bestånden kan fortfarande vara uttömda utanför denna zon. Islands beslut fick ett svar från Storbritannien, som förbjöd import av isländsk fisk. Som en stor exportmarknad för Islands viktigaste industri hoppades de att detta skulle föra dem till förhandlingsbordet.

1958, mot en bakgrund av misslyckad diplomati, Island utökade denna zon till 12 miles och förbjöd utländska flottor att fiska i dessa vatten, i strid med internationell rätt. Det ledde till det första av vad som blev känt som Torskkrigen – en handling i tre etapper som varade i nästan 20 år.

Under det första torskkriget, Royal Navy fregatter följde med den brittiska flottan in i Islands undantagszon för att fortsätta sitt fiske. En lek katt och råtta uppstod mellan de isländska kustbevakningsfartygen och de brittiska trålarna. Som svar på försök att gripa dem, trålarna rammade kustbevakningsfartygen och kustbevakningen hotade att öppna eld, även om större incidenter undveks.

1961, de två länderna kom så småningom överens om att Island fick behålla sin 12-milszon. I gengäld, Förenade kungariket beviljades villkorat tillträde till dessa vatten.

1972, dock, överfiske utanför denna gräns hade förvärrats och Island utökade sin exklusiva zon till 50 mil och sedan tre år senare, till 200 mil. Båda dessa drag ledde till fler sammandrabbningar mellan isländska trålare och Royal Navy eskortfartyg, respektive dubbade andra och tredje Cod Wars.

Isländska kustbevakningsfartyg bogserade anordningar utformade för att skära av ståltrålvajern (hawsers) från de brittiska trålarna – och fartyg från alla håll var inblandade i avsiktliga kollisioner. Även om dessa sammandrabbningar huvudsakligen var blodlösa, a British fisher was seriously injured when he was hit by a severed hawser and an Icelandic engineer died while repairing damage to a trawler that had clashed with a Royal Navy frigate.

In January 1976, British naval frigate HMS Andromeda collided with Thor, an Icelandic gunboat, which also sustained a hole in its hull. While British officials called the collision a "deliberate attack", the Icelandic Coastguard accused the Andomeda of ramming Thor by overtaking and then changing course. Eventually NATO intervened and another agreement was reached in May 1976 over UK access and catch limits. This agreement gave 30 vessels access to Iceland's waters for six months.

NATO's involvement in the dispute had little to do with fisheries and a large amount to do with the Cold War. Iceland was a member of NATO, and therefore aligned to the US, with a substantial US military presence in Iceland at the time. Iceland believed that NATO should intervene in the dispute but it had up until that point resisted. Popular feeling against NATO grew in Iceland and the US became concerned that this strategically important island nation – which allowed control of the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK) gap, an anti-submarine choke point – could leave NATO and worse, align itself with the Soviets.

Amid protests at the US military base in Iceland demanding the expulsion of the Americans, and growing calls from Icelandic politicians that they should leave NATO, the US put pressure on the British to concede in order to protect the NATO alliance. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters.

The loss of these Atlantic fishing grounds cost 1, 500 jobs in the home ports of the UK's distant water fleet, concentrated around Scotland and the north-east of England, with many more jobs lost in shore-based support industries. This had a significant negative impact on the fishing communities in these areas.

The UK also established its own 200-mile limit in response to Iceland's exclusion zone. These limits were eventually incorporated in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, giving similar rights to every sovereign nation. The creation of these "exclusive economic zones" (EEZ) was the first time that the international community had recognised that nations could own all of the resources that existed within the seas that surrounded them and exclude other nations from exploiting these resources.

The UK now owned the rights to the 200-mile zone around its islands, which contained some of the richest fishing grounds in Europe but up until this point the principle of "open seas" had existed, with Britain its most vocal champion. Fishing nations, had fished the high seas within 200 miles of their own and others coasts for centuries and now were restricted to their own.

British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

Economic trade offs

Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), dock, wasn't that exclusive.

On joining the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to a policy of sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other countries in return. The UN convention effectively gave the EEC one giant EEZ.

The UK government was willing to enter into the agreement as fisheries were one part of overall negotiations that would allow the UK to export goods and services to the European continent with significantly reduced trade barriers.

Although the fishing industry is of high local importance to fishing communities, it is relatively unimportant to the UK economy as a whole. 2016, the UK fishing industry (which includes the catching sector and all associated industries) was valued at £1.6 billion, against £1.76 trillion for the UK economy as a whole – or just under 1%. The UK's trade with the EU, both import and export, stands at £615 billion a year in comparison.

Enter the Common Fisheries Policy

1983, the Common Fisheries Policy was adopted, introducing management of European waters by giving each state a quota for what it could catch, based on a pre-determined percentage of total fishing opportunities. This was known as "relative stability" and was based on each country's historic fishing activity before 1983, which still determines how quotas are allocated today.

The formula that the EEC adopted, based on historic catches, is one of most contentious parts of the CFP for the UK. Many fishers have stories of the years running up to 1983, where foreign vessels increased their fishing activity in UK waters in order to secure a larger share of these fish in perpetuity. Although there is little evidence to support these views, it demonstrates the level of distrust in both the system, and foreign fishers, from the outset.

Som ett resultat, only 32% of fish caught in the UK EEZ today is caught by UK boats, with most of the remainder taken by vessels from other EU states, Norway and the Faroe Islands (who have also joined the CFP). Därför, non-UK vessels catch the remaining 68%, about 700, 000 tonnes, of fish a year in the UK EEZ.In return, the UK fleet lands about 92, 000 tonnes a year from other EU countries' waters.

Joining the CFP did not cause a decline in UK fish landings. Dock, in its early days, it did nothing to stop it. Fish landings continued to decline – and along with this, the industry itself contracted, using improved technology to offset the decline in stocks. Through the 1980s and into the early part of this century the imbalance – enshrined in the relative stability measure of the CFP – has led to the view that the CFP doesn't work in the UK's interests. Rather it allows the rest of the EU to take advantage of the country's fish stocks.

The CFP's quota system, while credited for helping the industry survive (and even reverse the collapse in fish stocks), is now seen as burdensome and preventing further growth.

A recent academic analysis of the current performance of the CFP showed it was not improving the management of the fish stock resources in any of its 17 criteria and was actually making things worse in seven areas.

Till exempel, a 2013 reform of the CFP introduced the landing obligation, the so-called "discard ban", that was designed to stop vessels discarding fish (bycatch) caught alongside the species they were targeting. Environmentalists, and campaigns backed by celebrities such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, have long voiced concerns over incidents of bycatch being dumped by fishers operating under the quota system.

This policy is now seen as potentially disastrous by some representatives of Britain's North Sea fishing fleet, as so many different types of fish live in the waters and bycatch is common and often unavoidable. They are concerned that boats would be forced to fill their holds with commercially worthless fish and return to port early. Or by exhausting their quota for some species early in the season, they would be forced to stay in port for the rest of the year, despite having quotas available for other species. Evidence given to the House of Lords suggests that this situation has not arisen as non-compliance and a lack of enforcement has undermined the discard ban.

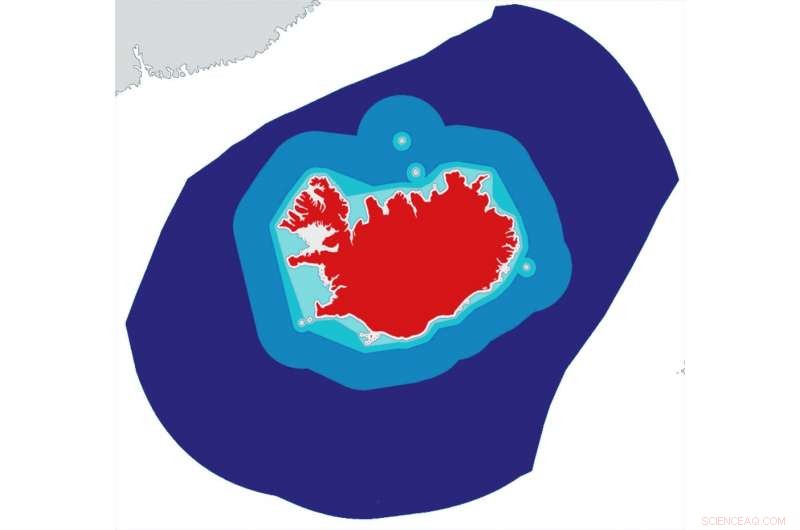

Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

When we interviewed fishers in north-east Scotland in 2018, we found many feared such blanket management across the entire EU would continue to damage their industry because it simply does not take into account the local environment that they work in.

Brexit

The depth of feeling among the UK fishing community was illustrated by the voting figures for the EU referendum in June 2016.

In Banff and Buchan, the constituency in Scotland containing Peterhead and Fraserburgh – the largest and third largest fishing ports in the UK respectively – 54% of people voted to leave the EU, with the size of the fishing industry given as the reason for this result. The result compared to 52% for the whole of the UK and just 38% for Scotland. A survey of members of the UK fishing industry before the vote indicated that 92.8% of correspondents believed that doing so would improve the UK fishing industry by some measure.

But will Brexit really bring the fishing revival so many have promised and hoped for? British politicians have promised a renaissance in UK fishing after leaving the EU. A Fisheries Bill was launched by the environment secretary, Michael Gove, with an aim to "take back control of UK waters". Dock, no definitive plan to remove the UK from the CFP in a transition deal has been made, nor has the industry been given any answers on future access for EU vessels, the apportionment of any new quota – if indeed the quota system remains as it is – the rules that they will be operating under, or even a date on which this will come into effect.

The UK government is seen by many in the fishing industry to be acting against their interests in pursuit of wider goals, for example by using the industry as a bargaining chip in wider UK trade negotiations with the EU.

The fishing industry's distrust of the government has a long tail:many believe they were sacrificed in 1973 by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, in order to secure access to the single market.

A soured relationship

Ironiskt, despite the fishing industry's support for Brexit and the popular campaign promises, our research suggests fishers don't simply want to close British waters to European fleets. We interviewed people who were sympathetic to their fellow fishers from abroad and did not wish to see businesses and livelihoods lost. They favour a re-balancing of quotas over time to allow EU vessels to adapt to the change, with all vessels having to adhere to UK rules. This would avoid any situations similar to the Scallop War by ensuring that all vessels with a quota have to abide by local restrictions.

The EU is the main export market for UK fish and fisheries products accounting for 70% of UK fisheries exports by value. Valued at £1.3 billion, this trade far exceeds the £980m value of fish landed in the UK, due to the added value from the processing sector. Some of the remaining 30% of exports that go to countries outside of the EU are governed by trade agreements negotiated by the EU that reduce trade barriers. So the single market, and additional trade agreements, are crucial to the success of the UK fishing industry.

This reliance on trade into the EU puts the industry in a position where unilaterally preventing access to UK waters would likely be met by reciprocal trade barriers and tariffs. This would increase the cost of their product, while reducing access to their biggest market. The question for the government, sedan, is how to balance a political issue against an economic one?

The issue centres on the word "control". If the UK has control of its waters that would simply mean that its government has the power to decide on anything from keeping fishing within UK waters purely for UK vessels, to remaining in or re-entering the CFP, or all points in between. Until the deals are negotiated and signed, the industry will remain in a limbo that has reopened old wounds and reignited distrust in the UK government.

Den här artikeln är återpublicerad från The Conversation under en Creative Commons-licens. Läs originalartikeln.