Illustration av Parker Solar Probe närmar sig solen. Kredit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben

Kärnan i att förstå vår rymdmiljö är kunskapen om att förhållandena i hela rymden – från solen till planeternas atmosfärer till strålningsmiljön i rymden – är sammankopplade.

Att studera detta samband - ett vetenskapsområde som kallas heliofysik - är en komplex uppgift:forskare spårar plötsliga utbrott av material, strålning, och partiklar mot bakgrund av det allestädes närvarande utflödet av solmaterial.

Ett sammanflöde av händelser i början av 2020 skapade ett nästan idealiskt rymdbaserat laboratorium, kombinerar inriktningen av några av mänsklighetens bästa observatorier – inklusive Parker Solar Probe, under sin fjärde solflygförbi—med en lugn period i solens aktivitet, när det är lättast att studera dessa bakgrundsförhållanden. Dessa förhållanden gav en unik möjlighet för forskare att undersöka hur solen påverkar förhållandena på punkter i rymden, med flera observationsvinklar och på olika avstånd från solen.

Solen är en aktiv stjärna vars magnetfält är spritt över hela solsystemet, bärs inom solens konstanta utflöde av material som kallas solvinden. Det påverkar rymdfarkoster och formar världarnas miljöer i hela solsystemet. Vi har sett solen, rymden nära jorden och andra planeter, och även de mest avlägsna kanterna av solens inflytandesfär i årtionden. Och 2018 markerade lanseringen av en ny, spelförändrande observatorium:Parker Solar Probe, med en plan att i slutändan flyga till cirka 3,83 miljoner miles från solens synliga yta.

Parker har nu haft fyra nära möten med solen. (Data från Parkers första möten med solen har redan avslöjat en ny bild av dess atmosfär.) Under sitt fjärde solmöte, som sträcker sig över delar av januari och februari 2020, rymdfarkosten passerade direkt mellan solen och jorden. Detta gav forskarna en unik möjlighet:Solvinden som Parker Solar Probe mätte när den var närmast solen skulle, dagar senare, komma till jorden, där vinden i sig och dess effekter kunde mätas av både rymdfarkoster och markbaserade observatorier. Vidare, solobservatorier på och nära jorden skulle ha en klar bild av platserna på solen som producerade solvinden mätt av Parker Solar Probe.

"Vi vet från Parkers data att det finns vissa strukturer som har sitt ursprung vid eller nära solytan. Vi måste titta på källregionerna för dessa strukturer för att fullt ut förstå hur de bildas, utveckla, och bidra till plasmadynamiken i solvinden, sa Nour Raouafi, projektforskare för Parker Solar Probe-uppdraget vid Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory i Laurel, Maryland. "Markbaserade observatorier och andra rymduppdrag ger stödjande observationer som kan hjälpa till att skapa en fullständig bild av vad Parker observerar."

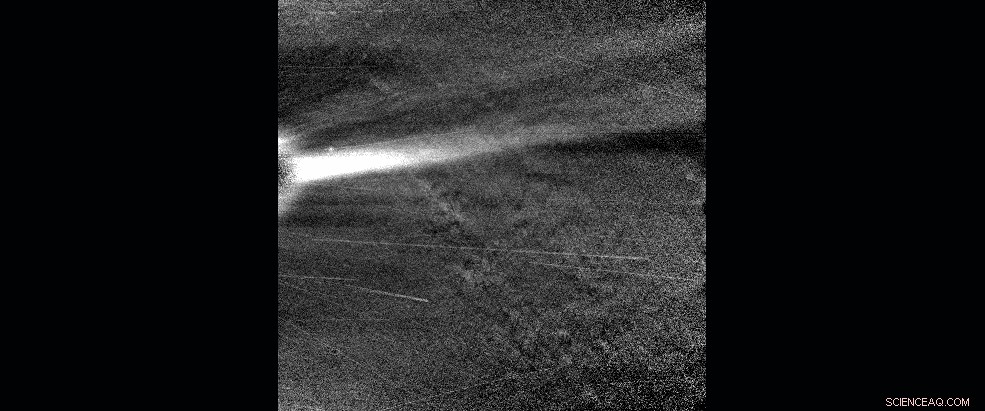

Denna animerade sekvens av bilder i synligt ljus från Parker Solar Probes WISPR-instrument visar en koronal streamer, observerades när Parker Solar Probe var nära perihelion den 28 januari, 2020. Kredit:NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Naval Research Lab/Parker Solar Probe

Denna himmelska inriktning skulle vara av intresse för forskare under alla omständigheter, men det sammanföll också med en annan astronomisk period av intresse för forskare:solminimum. Detta är punkten under solens regelbundna, cirka 11-åriga aktivitetscykler när solaktiviteten är på sin lägsta nivå - så plötsliga utbrott på solen som solflammor, koronala massutstötningar och energiska partikelhändelser är mindre sannolika. Och det betyder att att studera solen nära solminimum är en välsignelse för forskare som kan titta på ett enklare system och därmed reda ut vilka händelser som orsakar vilka effekter.

"Denna period ger perfekta förutsättningar för att spåra solvinden från solen till jorden och planeterna, sade Giuliana de Toma, en solforskare vid High Altitude Observatory i Boulder, Colorado, som ledde samordningen mellan observatorier för denna observationskampanj. "Det är en tid då vi lättare kan följa solvinden, eftersom vi inte har störningar från solen."

I årtionden, forskare har sammanställt observationer under dessa perioder av solminimum, en insats som leds av Sarah Gibson, en solforskare vid High Altitude Observatory, och andra vetenskapsmän. För var och en av de tre senaste solminimiperioderna, forskare slog samman observationer från en ständigt växande lista över observatorier i rymden och på marken, hoppas att rikedomen av data om den ostörda solvinden skulle avslöja ny information om hur den bildas och utvecklas. För denna minimiperiod för solenergi, forskare började samla in koordinerade observationer med början i början av 2019 under paraplyet Whole Heliosphere and Planetary Interactions, eller WHPI för kort.

Denna speciella WHPI-kampanj omfattade ett bredare antal observationer än någonsin:täckte inte bara solen och effekterna på jorden, men också data som samlats in på Mars och rymdens natur i hela solsystemet – allt i samklang med Parker Solar Probes fjärde och närmaste hittills förbi av solen.

WHPI-arrangörerna samlade observatörer från hela världen – och utanför. Att kombinera data från dussintals observatorier på jorden och i rymden ger forskare en chans att måla vad som kan vara den mest omfattande bilden någonsin av solvinden:från bilder av dess födelse med solteleskop, till prover strax efter att den lämnat solen med Parker Solar Probe, till flerpunktsobservationer av dess föränderliga tillstånd i hela rymden.

Läs vidare för att se exempel på de typer av data som fångats under detta internationella samarbete mellan sol- och rymdobservatorier.

Data från Mauna Loa Solar Observatory på Hawaii visar att en stråle av material kastas ut nära solens sydpol den 21 januari, 2020 (UTC). Denna skillnadsbild skapas genom att subtrahera pixlarna i föregående bild från den aktuella bilden för att markera ändringar. Kredit:Mauna Loa Solar Observatory/K-Cor

Parkers solsond

Tidiga data från Parker Solar Probes nära pass av solen under WHPI-kampanjen visar ett solvindssystem som är mer dynamiskt än vad som är synligt i observationer nära jorden. Särskilt, forskare hoppas att hela datauppsättningen – nedlänkad till jorden i maj 2020 – kommer att avslöja dynamiska strukturer, som små koronala massutkastningar och magnetiska flödesrep i deras tidiga utvecklingsstadier, som inte kan ses med andra observatorier som tittar längre bort. Koppla samman strukturer som denna, tidigare för liten eller för avlägsen för att se, med solvinds- och jordnära mätningar kan hjälpa forskare att bättre förstå hur solvinden förändras under hela sin livstid och hur dess ursprung nära solen påverkar dess beteende i hela solsystemet.

Mauna Loa solobservatorium

Parker Solar Probes närbilder av solvindsstrukturer kompletteras av solobservatorier på jorden och i rymden, som har ett större synfält för att fånga solvindstrukturer.

Data från Mauna Loa Solar Observatory på Hawaii visar att en stråle av material kastas ut nära solens sydpol den 21 januari, 2020. Koronala jetstrålar som detta är en solvindsfunktion som forskare hoppas kunna observera närmare med Parker Solar Probe, eftersom mekanismerna som skapar dem kunde kasta mer ljus över solvindens födelse och acceleration.

"Det skulle vara extremt lyckligt om Parker Solar Probe observerade detta jetplan, eftersom det skulle ge information om plasma och fältet i och runt strålen inte långt efter dess bildande, sa Joan Burkepile, ledande forskare för Coronal Solar Magnetism Observatory K-coronagraph instrument vid Mauna Loa Solar Observatory, som fångade dessa bilder.

Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory

Tillsammans med observationer av solvinden från Parker Solar Probe och nära jorden, scientists also have detailed images of the sun and its atmosphere from spacecraft like NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory. NASA's Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or STEREO, has a distinct view of the sun from its vantage point about 78 degrees away from Earth.

During this WHPI campaign, scientists took advantage of this unique viewing angle. From Jan. 21-23—when Parker Solar Probe and STEREO were aligned—the STEREO mission team increased the exposure length and frequency of images taken by its coronagraph, revealing fine structures in the solar wind as they speed out from the sun.

These difference images are created by subtracting the pixels of a previous image from the current image to highlight changes—here, revealing a small CME that would otherwise be difficult to see.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, takes high-resolution views of the entire sun, revealing fine details on the solar surface and the lower solar atmosphere. These images were captured in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light at 171 Angstroms, highlighting the quiet parts of the sun's outer atmosphere, koronan. This data—along with SDO's images in other wavelengths—maps much of the sun's activity, allowing scientists to connect solar wind measurements from Parker Solar Probe and other spacecraft with their possible origins on the sun.

Modeling the Data

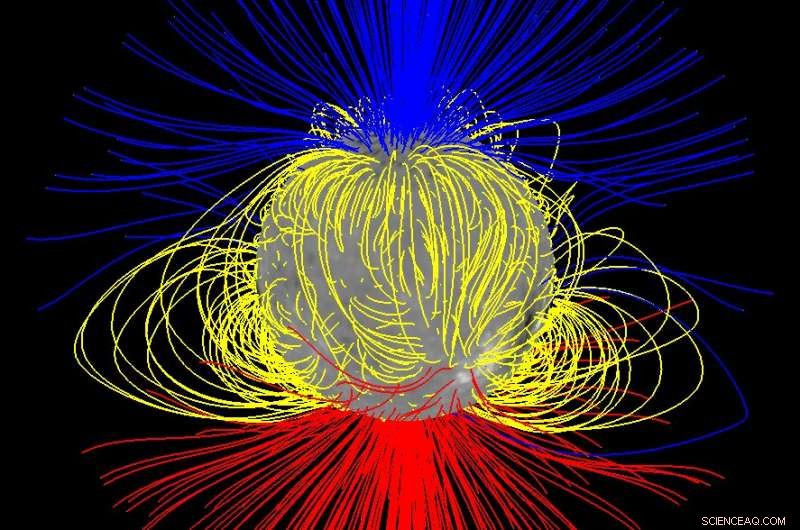

Helst scientists could use these images to readily pinpoint the region on the sun that produced a particular stream of solar wind measured by Parker Solar Probe—but identifying the source of any given solar wind stream observed by a spacecraft is not simple. I allmänhet, the magnetic field lines that guide the solar wind's movement flow out of the Northern half of the sun point in the opposite direction than they do in the Southern half. In early 2020, Parker Solar Probe's position was right at the boundary between the two—an area known as the heliospheric current sheet.

"For this perihelion, Parker Solar Probe was very close to the current sheet, so a little nudge one way or the other would make the magnetic footpoint shift to the south or north pole, " said Nick Arge, a solar scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "We were on the tipping point where sometimes it went north, sometimes south."

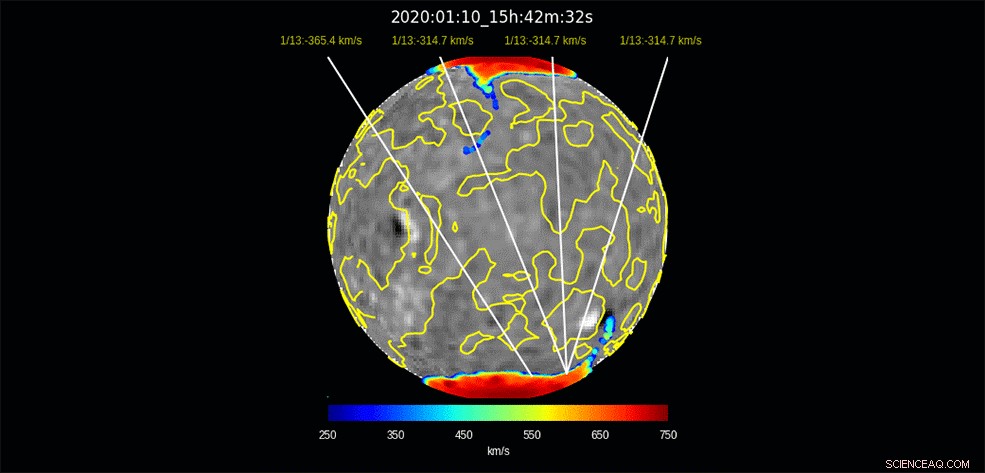

Predicting which side of the tipping point Parker Solar Probe was on was the responsibility of the modeling teams. Using what we know about the sun's magnetic field and the clues we can glean from distant images of the sun, they made day-by-day predictions of where, precisely, on the sun birthed the solar wind that Parker would fly through on a given day. Several modeling groups made daily attempts to answer just that question.

Using measurements of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, each group made a daily prediction for the source region producing the solar wind that Parker Solar Probe was flying through.

Arge worked with Shaela Jones, a solar scientist at NASA Goddard who did daily forecasting during the WHPI campaign, using a model originally developed by Arge and colleagues Yi-Ming Wang and Neil Sheeley, called the WSA model. According to their forecasts, the predicted source of the solar wind switched between hemispheres suddenly during the observation campaign, because Earth's orbit at the time was also closely aligned with the heliospheric current sheet—that region where the direction of magnetic polarity and the source of the solar wind switches between north and south. They predicted that Parker Solar Probe, flying in a similar plane as Earth, would experience similar switches in solar wind source and magnetic polarity as it flew near the sun.

Solar wind models rely on daily measurements of the sun's surface magnetic field—the black and white image underlaid. This particular model used measurements from the National Solar Observatory's Global Oscillation Network Group and a model that focuses on predicting how the sun's surface magnetic field will change over several days. Creating these magnetic surface maps is a complicated and imperfect process unto itself, and some of the modeling groups participating in the WHPI campaign also used magnetic measurements from multiple observatories. Detta, along with differences in each group's models, created a spread of predictions that sometimes placed the source of Parker Solar Probe's solar wind stream in two different hemispheres of the sun. But given the inherent uncertainty in modeling the solar wind's source, these different predictions can actually make for more robust operations.

The sun's "open" magnetic field — shown in this model in blue and red, with looped or closed field shown in yellow — primarily comes from near the Sun's north and south poles during solar minimum, but it spreads out to fill space converging near the Sun's equator. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge

"If you can observe the sun in two different places with two telescopes, you have a better chance to get the right spot, sa Jones.

Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar

The solar wind carries with it both an enormous amount of energy and the embedded magnetic field of the sun. When it reaches Earth, it can ring our planet's natural magnetic field like a bell, making it bend and deform—which produces a measurable change in magnetic field strength at certain points on Earth's surface. We track those changes because magnetic field oscillations can lead to a host of space weather effects that interfere with spacecraft or even, occasionally, utility grids on the ground.

A host of ground-based magnetometers have tracked these effects since the 1850s, and they're one of the many sets of data scientists are gathering in connection with this campaign. Other ground-based instruments can reveal the invisible effects of space weather in our atmosphere. One such system is the Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar, or PFISR—a radar system based at the Poker Flat Research Range near Fairbanks, Alaska.

This radar is specially tuned to detect one of most reliable indicators of a disturbance in Earth's magnetic field:electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere. These electrons are created when particles trapped in the magnetosphere are sent zooming into Earth's atmosphere by a complex series of events, a set of circumstances known as a magnetospheric substorm.

On Jan. 16, PFISR measured the changing electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere during one such substorm. During a substorm, particles cascade into the upper atmosphere, not only creating the shower of electrons measured by the radar, but driving a more visible effect:the aurora. PFISR uses multiple beams of radar oriented in different directions, which allowed scientists to build up a three-dimensional picture of how electrons in the atmosphere changed throughout the substorm.

This model run — produced by Nick Arge and Shaela Jones using the WSA model — illustrates the predicted origin for solar wind that will impact Earth days later, spanning Jan. 10 – Feb. 3, 2020. The colored regions near the sun's north and south poles show the regions from which the solar wind flows out, with red regions showing a faster flow and blue regions showing a slower flow. The yellow lines on the sun divide areas of opposite magnetic polarity. The white lines indicate the predicted points of origin for the solar wind arriving at Earth at the given date. The black and white underlaid image shows a map of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, the basis for the model's predictions. The black regions are where the magnetic field points inward, toward the sun, and white regions are where the field points outward, away from the sun. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge/Shaela Jones

Because this substorm took place so early in the observation campaign—only one day after data collection began—it's unlikely that it was caused by conditions on the sun observed during the campaign. But even so, the connection between magnetospheric substorms and the broader, global-scale effects created by the solar wind—called geomagnetic storms—isn't entirely understood.

"This substorm didn't happen during a geomagnetic storm time, " said Roger Varney, principal investigator for PFISR at SRI International in Menlo Park, Kalifornien. "The solar wind during this event is fluctuating, but not particularly strongly—it's basically background noise. But solar wind is basically never steady; it's constantly putting some energy into the magnetosphere."

This deposit of energy into Earth's magnetic system has far-reaching effects:for one, changes in the composition and density of Earth's upper atmosphere can garble communications and navigation signals, an effect often characterized by total electron content. Changes in density can also affect the orbits of satellites to great degree, introducing uncertainty about precise position.

MAVEN

Earth isn't the only planet where the solar wind has measurable effects—and studying other worlds in our solar system can help scientists understand some of the solar wind's effects on Earth and how it influenced the evolution of Earth and other worlds throughout the solar system's history.

At Mars, the solar wind coupled with Mars' lack of a global magnetic field may be a major factor in the dry, barren world the Red Planet is today. Though Mars was once much like Earth—warm, with liquid water and a thick atmosphere—the planet has changed drastically over the course of its four-billion-year history, with most of its atmosphere being stripped away to space. With similar processes observed here on Earth, scientists leverage understanding of solar-planetary interactions at Mars to determine how processes leading to atmospheric escape has the ability to change whether a planet is habitable or not. I dag, the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission, or MAVEN, studies these processes at Mars. MAVEN observations at Mars are available for this latest WHPI campaign.

Over the coming months, heliophysicists around the world will begin to study data from these observatories in depth, hoping to draw connections that reveal new knowledge about the sun and its changes that influence Earth and space across the solar system.

Parker Solar Probe is part of the NASA Heliophysics Living with a Star program to explore aspects of the sun-Earth system that directly affect life and society. The Living with a Star program is managed by the agency's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, designad, built and operates the spacecraft and manages the mission for NASA.