Drosophila melanogaster. Kredit:Columbia's Zuckerman Institute

Flugsparkningssäsongen är här. Inte förr kommer du att lägga dina färska jordgubbar på köksbänken förrän den första fruktflugan kommer. Det kommer inte ta lång tid för en pluton av Drosophila-kompisar att sväva runt bytet.

Om du väljer att slå, svepa, slå, backhand eller på annat sätt utöva dina insekticida böjelser, slösa inte bort ett läromedel. Allt du behöver göra är att omfamna den tidlösa maximen:Lär känna din fiende. Fruktflugan är en bas i labbet och har visat sig vara en oändlig källa till biologisk inspiration och kunskap om hur hjärnan och kroppen utvecklas och fungerar.

Lektion ett:Fruktflugor har funnits längre än vi har gjort – mycket längre

Troligtvis kommer du att misslyckas i din iver att ta bort dina interna fruktflugor. Det är inte så att du är oduglig på att rada upp dina dödliga slag. Det är bara det att evolutionen har finslipat flugornas små hjärnor, vingar, sensoriska system, muskulatur och inre organ i konsten att överleva i cirka 40 miljoner år. Det är 38 miljoner fler år än det har tagit för oss Homo sapiens att utvecklas från våra Australopithecus-förfäder. Fruktflugor har gått i evolution skolan mycket längre än mänskligheten.

Lektion två:Fruktflugor har en kultföljd inom vetenskapen

Tidigt på 1900-talet var en av de första forskarna som tog emot denna omedvetna gåva till vetenskapen Thomas Hunt Morgan från Columbia University. 1910 märkte Morgan att han lätt kunde upptäcka mutationer, som stora vita ögon istället för flugornas vanliga stora röda. Han och hans labbkamrater lärde sig hur man kopplar dessa fysiska mutationer till specifika genetiska sträckor som finns längs insekternas kromosomer.

Sedan dess har dessa diminutiva leddjur förblivit älskade och avslöjande forskningspartners. För mycket av det vi vet om genetik, arv, biologisk utveckling, sensorisk vetenskap, många sjukdomar och otaliga andra aspekter av biologin har vi fruktflugor att tacka. En nyligen genomförd undersökning av forskarsamhället för fruktflugor visade att en uppskattning av mer än 6 000 "flugarbetare över hela världen verkar konservativa."

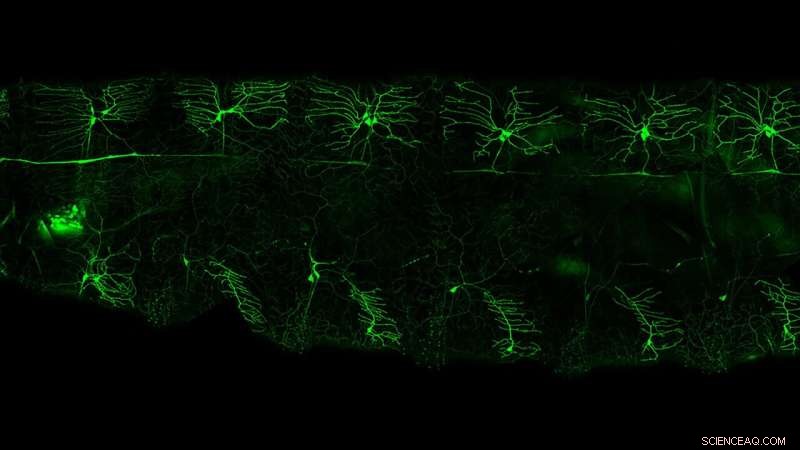

Fluorescerande etiketter avslöjar sensoriska celler från en fluglarv. Kredit:Grueber Lab; Zuckerman Institute

Lektion tre:Fruktflugor är små Houdinis

När den står inför ett hot kan en fruktfluga reagera nästan omedelbart. To make basic evasive movements, the insect, even in its larval stages, has to keep precise track of where its body is in space. This body-place sense, common to all animals, is termed proprioception. It allows humans, for example, to know where their limbs are without looking directly at them and to make fine adjustments during any movement, such as reaching for a strawberry.

Wesley Grueber, Ph.D., and his colleagues at Columbia's Zuckerman Institute discovered that a collection of sensory cells in the fly allow it to keep precise track of where different body regions are located during movement.

Dr. Grueber points out that similar cells and circuits probably kick in when flies make those aeronautic escape sequences that have you cursing in the kitchen. That is, unless your deftly executed backhands squash the fleeing fruit flies, so that their previous and gorgeous marriage of form and function morphs into entropic functionless stains.

Lesson four:Fruit flies have 1,600 eyes, sort of

If you could pick through the aftermath of a swatted fruit fly's 580,000 or so cells, you would find at least some of the 800 light-harvesting facets, or ommatidia, that comprise each of a fly's eyes. You might also find remains of the 200,000 neurons that make up the fly's nervous system and thereby the circuitry it had used to see the world.

You would also be wandering into the territory of Rudy Behnia, Ph.D., a principal investigator at the Zuckerman Institute. Among other things, Dr. Behnia has been teasing out the cellular circuitry and computations that underlie fruit flies' color vision.

"Spectral information in the world is very rich and flies could use it for object recognition," as well as for determining the time of day and navigating with cues about the sun's location from the sky's color, Dr. Behnia says.

As is evident from your terrible batting average when it comes to fly-squishing, your insect nemeses know your murderous hand is coming. This intel derives from signal-delay circuitry built into the fruit fly's visual system. If the initial sensory signals change between ommatidia, as happens when your hand is sweeping through a fly's field of view, the resulting signal patterns deeper in the fly's brain carry information about the direction your hand is moving.

Now add in the fly's phototaxis, which plays into its knack for detecting and moving toward ultraviolet light, and you have the neurobiological foundation for an escape plan. "Since most objects in nature reflect rather than absorb ultraviolet radiation, the main source of natural UV is the open sky," Dr. Behnia explains. That means that if you are a fruit fly, and you detect ill will coming your way, you just need to follow that UV to the open sky.

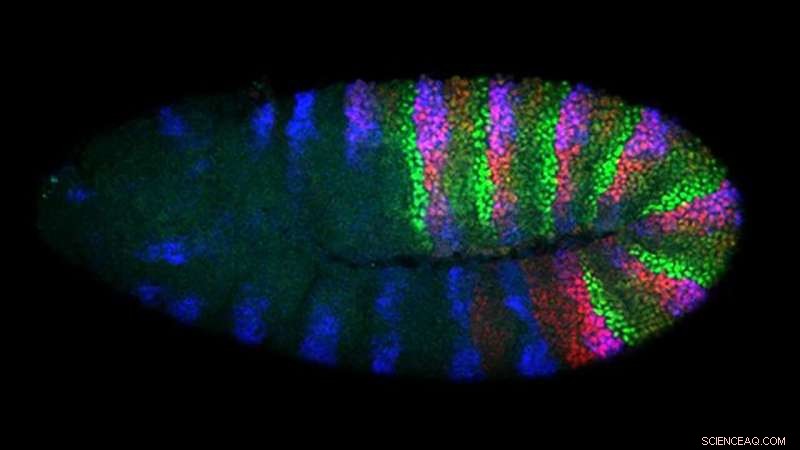

Fluorescent labels demarcate larval locations of specific Hox genes. Credit:Mann Lab; Zuckerman Institute

Lesson five:Fruit flies do mind-bending math, all in their heads

To plot their course through the world, and escape trajectories in times of peril, fruit flies use external reference points, such as the position of the sun, along with serious mental mathematics.

"The flies are doing trigonometry," says Larry Abbott, Ph.D., co-director of the Center for Theoretical Neuroscience at the Zuckerman Institute. "It's incredible."

A fly's mental computations start by representing vectors, mathematical arrows with angles and lengths that themselves represent the direction and speed of motion. Dr. Abbott and his colleagues discovered that the flies use wave-like patterns of brain activity to encode these vectors. The amplitudes and phases of those neural wave patterns match the lengths and angles of the corresponding vectors in actual space.

"Flies perform the types of vector calculations often assigned in introductory physics classes, but they do this in ways that are not typically taught in such courses," says Dr. Abbott, adding that he is looking forward to the arrival, later this summer, to a new colleague at the Zuckerman Institute, Dr. Gwyneth Card. She will investigate the neural circuitry flies use to decide exactly what escape response to enact, say, as a threatening human hand violates their personal space.

Lesson six:The same genes that grow humans grow flies

A fly contains half a million cells, distributed among more than 200 cell types and organized into body parts ranging from the antennae on the front of its head to the hairs on its posterior. This sophisticated body plan emerges from a fertilized egg thanks to a mere eight genes in the Hox family:the master conductors of development.

Over many years of investigations, Richard Mann, Ph.D., another Zuckerman neuroscientist who studies fruit flies, has been teasing out how Hox genes, transcription factors, and many other genes and proteins coordinate their fly-building feats according to a brilliant logic of biological development. What scientists learn about this logic in model organisms like fruit flies often points to analogous developmental logic in people, says Dr. Mann. He stresses that the genetic common ground for humans and fruit flies extends beyond development genes. Says Mann:"So many human genes are also found in flies and a majority of human disease genes are also found in flies."

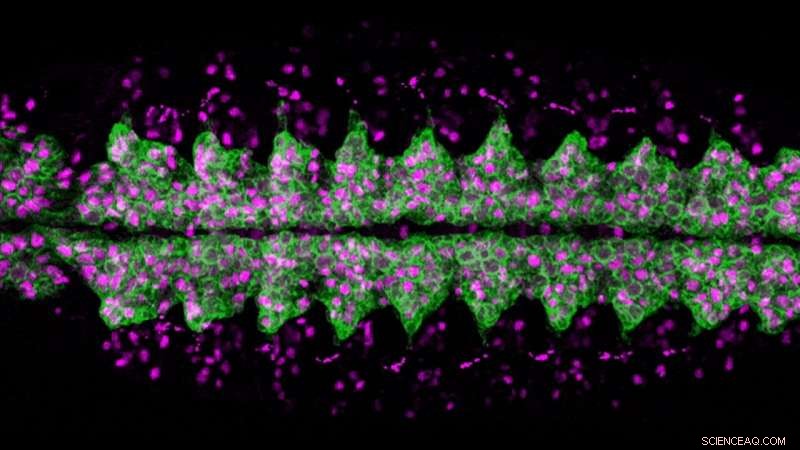

A green stain reveals neuroblasts, which are precursor cells that become neurons, specifically in the nerve cord of a fly embryo; the magenta stain lights up neuroblasts residing both within and without of the nerve cord. Credit:Kohwi Lab; Zuckerman Institute

Lesson seven:Fruit flies are symphonies of genetic and cellular notes

Extracting yet more biological insight from fruit fly genes is Zuckerman Institute principal investigator Minoree Kohwi, Ph.D.. She has been identifying the specific places and times in which development genes become active in sequential generations of cells of a growing fruit fly.

"Think of each gene as a single musical note:by itself, a note is an isolated sound, but play each note at the right time for just the right duration, and you get a beautiful symphony," Dr. Kohwi said.

One of the big questions she aims to answer is this:"How are the thousands of different cell types produced in such an organized manner to allow proper brain function?"

Dr. Kohwi's lab is uncovering the origins of a fly brain's many different cell types and thereby helping to reveal the origins of a similar diversity of cells in her own brain. Her research excavates deep into the molecular foundations of life by revealing how and when development genes migrate to different locations within a cell's nucleus. These migrations regulate when specific development genes are active and when they are repressed. And those on-off sequences, Dr. Kohwi says, "ultimately determine when each brain cell type can be made during development."

Squashing a miracle

Few Drosophila researchers would think twice about defending the fresh fruit on their tables with lethal force. But because of what they know about the marvels of fruit flies, you might see a flash of fly-admiration on their faces in the moment you hear thwap.