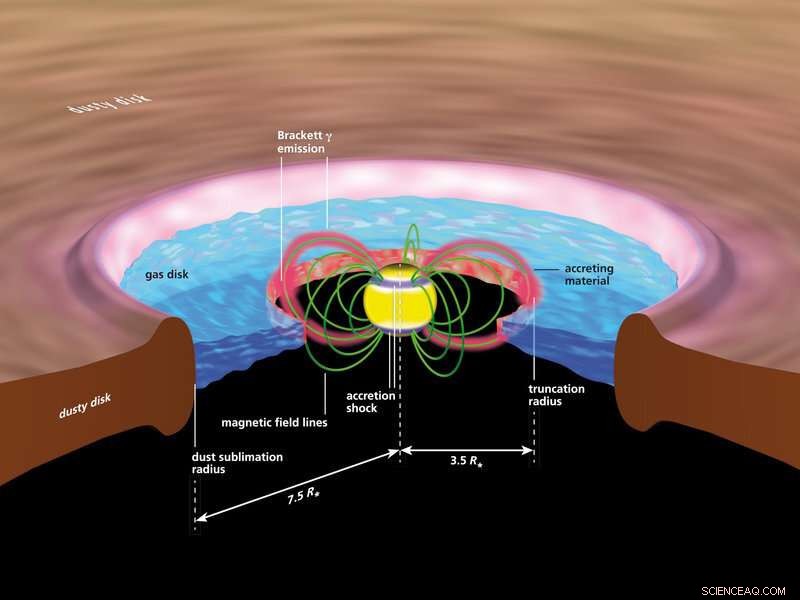

Konstnärligt intryck av de heta gasströmmarna som hjälper unga stjärnor att växa. Magnetiska fält leder materia från den omgivande cirkumstellära skivan, planeternas födelseplats, till stjärnans yta, där de producerar intensiva strålningar. Kredit:A. Mark Garlick

Astronomer har använt GRAVITY-instrumentet för att studera en ung stjärnas omedelbara närhet mer i detalj än någonsin tidigare. Deras observationer bekräftar en trettio år gammal teori om tillväxten av unga stjärnor:magnetfältet som produceras av stjärnan själv riktar material från en omgivande ansamlingsskiva av gas och damm mot dess yta. Resultaten, publiceras idag i tidskriften Natur , hjälpa astronomer att bättre förstå hur stjärnor som vår sol bildas och hur jordliknande planeter produceras från skivorna som omger dessa stjärnbebisar.

När stjärnor bildas, de börjar relativt små och är belägna djupt inne i ett gasmoln. Under de kommande hundratusentals åren, de drar mer och mer av den omgivande gasen på sig själva, öka sin massa i processen. Med hjälp av GRAVITY-instrumentet, en grupp forskare som inkluderar astronomer och ingenjörer från Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), har nu hittat de mest direkta bevisen hittills för hur den gasen leds till unga stjärnor:den styrs av stjärnans magnetfält till ytan i en smal kolumn.

De relevanta längdskalorna är så små att inte ens med de bästa teleskop som för närvarande finns tillgängliga är inga detaljerade bilder av processen möjliga. Fortfarande, använder den senaste observationstekniken, astronomer kan åtminstone få lite information. För den nya studien, forskarna använde sig av den enastående höga upplösningsförmågan hos instrumentet som kallas GRAVITY. Den kombinerar fyra 8-meters VLT-teleskop från European Southern Observatory (ESO) vid Paranal-observatoriet i Chile till ett virtuellt teleskop som kan urskilja små detaljer liksom ett teleskop med en 100-meters spegel.

Genom att använda GRAVITY, forskarna kunde observera den inre delen av gasskivan som omger stjärnan TW Hydrae. "Den här stjärnan är speciell eftersom den är väldigt nära jorden på bara 196 ljusår bort, och materiaskivan som omger stjärnan är direkt vänd mot oss, säger Rebeca García López (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies och University College Dublin), huvudförfattare och ledande vetenskapsman för denna studie. "Detta gör det till en idealisk kandidat för att undersöka hur materia från en planetbildande skiva kanaliseras till stjärnytan."

Observationen gjorde det möjligt för astronomerna att visa att nära-infraröd strålning som sänds ut av hela systemet verkligen har sitt ursprung i det innersta området, där vätgas faller på stjärnans yta. Resultaten pekar tydligt mot en process som kallas magnetosfärisk accretion, det är, infallande materia styrd av stjärnans magnetfält.

Stjärnfödsel och stjärntillväxt

En stjärna föds när ett tätt område i ett moln av molekylär gas kollapsar under sin egen gravitation, blir betydligt tätare, värms upp under processen, tills slutligen densiteten och temperaturen i den resulterande protostjärnan är så hög att kärnfusion av väte till helium startar. För protostjärnor upp till ungefär två gånger solens massa, de tio eller så miljoner åren direkt före antändningen av proton-proton kärnfusion utgör den så kallade T Tauri-fasen (uppkallad efter den första observerade stjärnan av detta slag, T Tauri i stjärnbilden Oxen).

Stjärnor som vi ser i den fasen av deras utveckling, känd som T Tauri stjärnor, lysa ganska starkt, speciellt i infrarött ljus. Dessa så kallade "unga stjärnobjekt" (YSOs) har ännu inte nått sin slutliga massa:de är omgivna av resterna av molnet från vilket de föddes, i synnerhet av gas som har dragit ihop sig till en cirkumstellär skiva som omger stjärnan. I de yttre delarna av skivan, damm och gas klumpar ihop sig och bildar allt större kroppar, som så småningom kommer att bli planeter. Stora mängder gas och damm från det inre skivområdet, å andra sidan, dras till stjärnan, öka sin massa. Sist men inte minst, stjärnans intensiva strålning driver ut en betydande del av gasen som en stjärnvind.

Riktlinjer till ytan:stjärnans magnetfält

Naivt, man kan tro att transport av gas eller damm till en massiv, graviterande kropp är lätt. Istället, det visar sig inte alls vara så enkelt. På grund av vad fysiker kallar bevarandet av rörelsemängd, det är mycket mer naturligt för alla objekt – vare sig det är planet eller gasmoln – att kretsa runt en massa än att falla rakt ned på dess yta. En anledning till att viss materia ändå lyckas nå ytan är en så kallad accretion disk, i vilken gas kretsar kring den centrala massan. There is plenty of internal friction inside that continually allows some of the gas to transfer its angular momentum to other portions of gas and move further inward. Än, at a distance from the star of less than 10 times the stellar radius, the accretion process gets more complex. Traversing that last distance is tricky.

Thirty years ago, Max Camenzind, at the Landessternwarte Königstuhl (which has since become a part of the University of Heidelberg), proposed a solution to this problem. Stars typically have magnetic fields—those of our Sun, till exempel, regularly accelerate electrically charged particles in our direction, leading to the phenomenon of Northern or Southern lights. In what has become known as magnetospheric accretion, the magnetic fields of the young stellar object guide gas from the inner rim of the circumstellar disk to the surface in distinct column-like flows, helping them to shed angular momentum in a way that allows the gas to flow onto the star.

In the simplest scenario, the magnetic field looks similar to that of the Earth. Gas from the inner rim of the disk would be funneled to the magnetic North and to the magnetic South pole of the star.

Checking up on magnetospheric accretion

Having a model that explains certain physical processes is one thing. Dock, it is important to be able to test that model using observations. But the length scales in question are of the order of stellar radii, very small on astronomical scales. Tills nyligen, such length scales were too small, even around the nearest young stars, for astronomers to be able to take a picture showing all relevant details.

Schematic representation of the process of magnetospheric accretion of material onto a young star. Magnetic fields produced by the young star carry gas through flow channels from the disk to the polar regions of the star. The ionized hydrogen gas emits intense infrared radiation. When the gas hits the star's surface, shocks occur that give rise to the star's high brightness. Credit:MPIA graphics department

First indication that magnetospheric accretion is indeed present came from examining the spectra of some T Tauri stars. Spectra of gas clouds contain information about the motion of the gas. For some T Tauri stars, spectra revealed disk material falling onto the stellar surface with velocities as high as several hundred kilometers per second, providing indirect evidence for the presence of accretion flows along magnetic field lines. In a few cases, the strength of the magnetic field close to a T Tauri star could be directly measured by a combining high-resolution spectra and polarimetry, which records the orientation of the electromagnetic waves we receive from an object.

På senare tid, instruments have become sufficiently advanced—more specifically:have reached sufficiently high resolution, a sufficiently good capability to discern small details—so as to allow direct observations that provide insights into magnetospheric accretion.

The instrument GRAVITY plays a key role here. It was developed by a consortium that includes the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, led by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. In operation since 2016, GRAVITY links the four 8-meter-telescopes of the VLT, located at the Paranal observatory of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). The instrument uses a special technique known as interferometry. The result is that GRAVITY can distinguish details so small as if the observations were made by a single telescope with a 100-m mirror.

Catching magnetic funnels in the act

In the Summer of 2019, a team of astronomers led by Jerome Bouvier of the University of Grenobles Alpes used GRAVITY to probe the inner regions of the T Tauri Star with the designation DoAr 44. It denotes the 44th T Tauri star in a nearby star forming region in the constellation Ophiuchus, catalogued in the late 1950s by the Georgian astronomer Madona Dolidze and the Armenian astronomer Marat Arakelyan. The system in question emits considerable light at a wavelength that is characteristic for highly excited hydrogen. Energetic ultraviolet radiation from the star ionizes individual hydrogen atoms in the accretion disk orbiting the star.

The magnetic field then influences the electrically charged hydrogen nuclei (each a single proton). The details of the physical processes that heat the hydrogen gas as it moves along the accretion current towards the star are not yet understood. The observed greatly broadened spectral lines show that heating occurs.

For the GRAVITY observations, the angular resolution was sufficiently high to show that the light was not produced in the circumstellar disk, but closer to the star's surface. Dessutom, the source of that particular light was shifted slightly relative to the centre of the star itself. Both properties are consistent with the light being emitted near one end of a magnetic funnel, where the infalling hydrogen gas collides with the surface of the star. Those results have been published in an article in the journal Astronomi &Astrofysik .

De nya resultaten, which have now been published in the journal Natur , go one step further. I detta fall, the GRAVITY observations targeted the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. They are based on GRAVITY observations of the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. It is probably the best-studied system of its kind.

Too small to be part of the disk

With those observations, Rebeca García López and her colleagues have pushed the boundaries even further inwards. GRAVITY could see the emissions corresponding to the line associated with highly excited hydrogen (Brackett-γ, Brγ) and demonstrate that they stem from a region no more than 3.5 times the radius of the star across (about 3 million km, or 8 times the distance the distance between the Earth and the Moon).

This is a significant difference. According to all physics-based models, the inner rim of a circumstellar disk cannot possibly be that close to the star. If the light originates from that region, it cannot be emitted from any section of the disk. At that distance, the light also cannot be due to a stellar wind blown away by the young stellar object—the only other realistic possibility. Tagen tillsammans, what is left as a plausible explanation is the magnetospheric accretion model.

Vad kommer härnäst?

In future observations, again using GRAVITY, the researchers will try to get data that allows them a more detailed reconstruction of physical processes close to the star. "By observing the location of the funnel's lower endpoint over time, we hope to pick up clues as to how distant the magnetic North and South poles are from the star's axis of rotation, " explains Wolfgang Brandner, co-author and scientist at MPIA. If North and South Pole directly aligned with the rotation axis, their position over time would not change at all.

They also hope to pick up clues as to whether the star's magnetic field is really as simple as a North Pole–South Pole configuration. "Magnetic fields can be much more complicated and have additional poles, " explains Thomas Henning, Director at MPIA. "The fields can also change over time, which is part of a presumed explanation for the brightness variations of T Tauri stars."

Allt som allt, this is an example of how observational techniques can drive progress in astronomy. I detta fall, the new observational techniques embody in GRAVITY were able to confirm ideas about the growth of young stellar objects that were proposed as long as 30 years ago. And future observations are set to help us understand even better how baby stars are being fed.