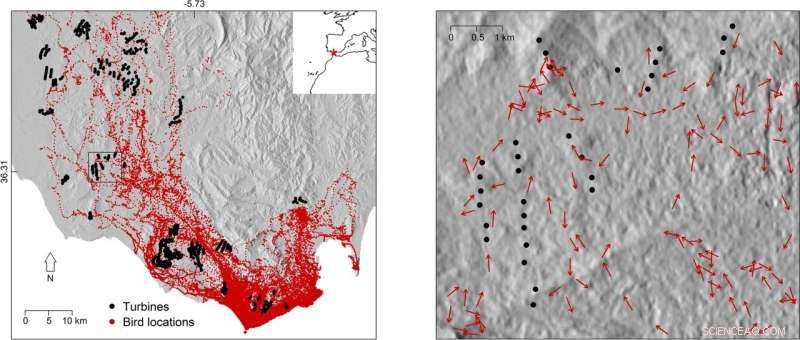

Vänster panel visar den rumsliga fördelningen av fågel- och turbinlägen i studieområdet mellan Cadiz och Tarifa (södra Spanien). Röd asterisk uppe till höger markerar platsen för studieområdet. Höger panel visar fågelflygningsriktningar i jämförelse med turbinlägen i en liten del av studieområdet (fyrkant i den vänstra panelen). Kulleskuggning lades till som bakgrund för att illustrera samspelet mellan användning av fågelutrymme och topografi. Data som användes för att illustrera kulleskuggning hämtades från en allmänt tillgänglig digital höjdmodell (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov). Kredit:Scientific Reports (2022). DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-10295-9

I kapplöpningen för att undvika skenande klimatförändringar drivs två förnybara energitekniker fram som lösningen för att driva mänskliga samhällen:vind och sol. Men i många år har vindkraftverk varit på kollisionskurs med naturvården. Fåglar och andra flygande djur riskerar att dö genom att stöta med rotorbladen på turbiner, vilket väcker frågor om huruvida vind är en hörnsten i en global politik för ren energi. Nu har ett par djurspårningsstudier från Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior och University of East Anglia, Storbritannien, tillhandahållit detaljerad GPS-data om flygbeteende för fåglar som är mottagliga för kollision med energiinfrastruktur. Den första, en storskalig studie av 1 454 fåglar från 27 arter, har identifierat hotspots i Europa där fåglar är särskilt utsatta för vindkraftverk och kraftledningar. Den andra zoomade in på hur fåglar beter sig när de flyger nära turbiner, och avslöjar att individer aktivt kommer att undvika turbiner om de är inom en kilometer. Genom att spåra fåglars rörelser med GPS-enheter med hög precision ger båda studierna de detaljerade biologiska data som behövs för att utöka infrastrukturen för förnybar energi med minimal påverkan på vilda djur.

Vindenergiproduktionen har ökat under de senaste två decennierna med det globala engagemanget för övergång till förnybar energi från koldioxidutsläppande fossila bränslen. Europeisk landbaserad vindenergikapacitet förväntas växa nästan fyrdubblad fram till 2050, och länder i Mellanöstern och Nordafrika, som Marocko och Tunisien, har också mål att öka andelen elförsörjning från landbaserad vindkraft.

"We know from previous research that there are many more suitable locations to build wind turbines than we need in order to meet our clean energy targets up to 2050," said lead author Jethro Gauld, a Ph.D. researcher in the School of Environmental Sciences at University of East Anglia. "If we can do a better job of assessing risks to biodiversity, such as collision risk for birds, into the planning process at an early stage we can help limit the impact of these developments on wildlife while still achieving our climate targets."

Pinpointing collision hotspots in Europe

An international team of 51 researchers from 15 countries, including the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany, collaborated to identify the areas where these birds would be more sensitive to onshore wind turbine or power line development. The study, published in Journal of Applied Ecology , used GPS location data from 65 bird tracking studies to understand where they fly more frequently at danger height—defined as 10 to 60 meters above ground for power lines and 15 to 135 meters for wind turbines. "GPS tracking provides very accurate data on location and flight height, which cannot be obtained from direct observation, particularly from large distances," says Martin Wikelski, director at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and co-author on the study. "This study represents the first time GPS data from so many species has been pooled to create a comprehensive picture of where birds are at risk.

The resulting vulnerability maps reveal that the collision hotspots are particularly concentrated within important migration routes, along coastlines and near breeding locations. These include the Western Mediterranean coast of France, Southern Spain and the Moroccan Coast—such as around the Strait of Gibraltar—Eastern Romania, the Sinai Peninsula and the Baltic coast of Germany. The GPS data collected related to 1,454 birds from 27 species, mostly large soaring ones such as white storks. Exposure to risk varied across the species, with the Eurasian spoonbill, European eagle owl, whooper swan, Iberian imperial eagle and white stork among those flying consistently at heights where they risk collision. The authors say development of new wind turbines and transmission power lines should be minimized in these high sensitivity areas, and any developments which do occur will likely need to be accompanied by measures to reduce the risk to birds.

How birds behave near turbines

As well as providing location and flight height, GPS loggers open up an additional frontier in efforts to better plan energy infrastructure. "With GPS tracking we are able to understand exactly how birds behave as they fly close to the turbines," says Carlos Santos, an Affiliated Scientist of the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and an Assistant Professor at the Federal University of Pará, in Brazil. "Knowing how close they fly, and whether or not wind or other factors influence their flight behavior, is very important to mitigate collision rates as it can help better planning of wind farms."

A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and the University of East Anglia focused their attention on the black kite, a very common soaring bird that migrates through the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow straight between southern Spain and North Africa. "The Strait of Gibraltar is the main migratory bottleneck for birds in western Europe but it's also a hotspot for wind farms," says Santos. "We wanted to see how soaring birds behave in this area, which represent a serious threat during their migration to Africa."

This study, published in Scientific Reports , looked at GPS information from 126 black kites as the birds approached wind turbines. The data showed that birds avoided flight paths straight to turbines as they flew closer to them. The birds started to deviate from turbines one kilometer away, but this effect was even more pronounced within 750 meters and when the wind was blowing towards the turbines. "This means that they recognize the risk of the turbines and keep a safe distance from them," says Santos.

The authors say collecting GPS data from the interaction between birds and turbines is extremely difficult. Says Santos:"You need to tag many animals to increase the chances of recording their behavior near the turbines. This is why our dataset is so uncommon. Fortunately, GPS tracking studies are becoming more common and hopefully in the near future we will be able to gather data of this sort for other soaring bird species." The authors stress that understanding how the birds perceive wind turbines and which factors attenuate or exacerbate their perception is critical to learn where to place turbines and to develop effective deterrents.