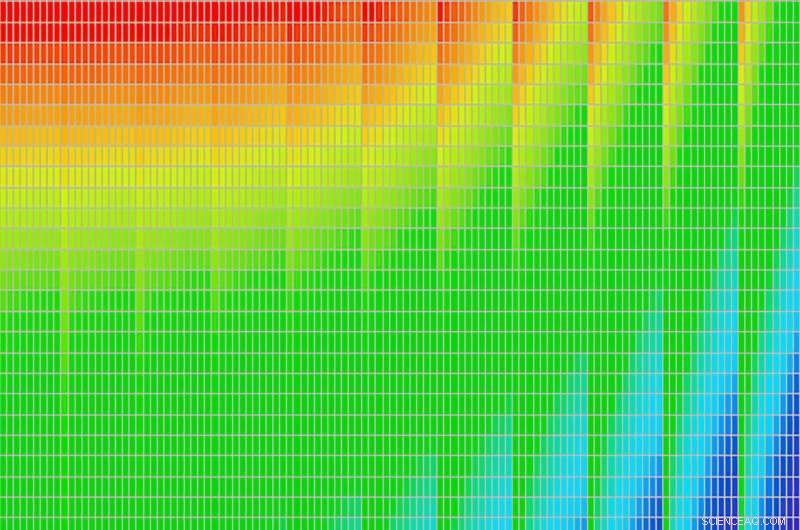

Forskare vid Icahn School of Medicine vid Mount Sinai utvecklade en avancerad metod för att avgöra om celler kan använda ett obskyrt DNA-taggningssystem för att slå på eller av gener. Kredit:Do lab, Mount Sinai, N.Y., N.Y.

I decennier har en liten grupp avancerade medicinska forskare studerat ett biokemiskt DNA-taggningssystem som slår på eller av gener. Många har studerat det i bakterier och nu har några sett tecken på det i växter, flugor och till och med mänskliga hjärntumörer. Men enligt en ny studie av forskare vid Icahn School of Medicine vid Mount Sinai kan det finnas ett problem:mycket av bevisen för dess närvaro i högre organismer kan bero på bakteriell kontaminering, vilket var svårt att upptäcka med nuvarande experimentella metoder.

För att ta itu med detta skapade forskarna en skräddarsydd gensekvenseringsmetod som bygger på en ny maskininlärningsalgoritm för att exakt mäta källan och nivåerna av taggat DNA. Detta hjälpte dem att skilja bakteriellt DNA från det från mänskliga och andra icke-bakteriella celler. Medan resultaten publiceras i Science stödde tanken att detta system kan förekomma naturligt i icke-bakteriella celler, nivåerna var mycket lägre än några tidigare studier rapporterade och var lätt förvrängda av bakteriell kontaminering eller nuvarande experimentella metoder. Experiment på mänskliga hjärncancerceller gav liknande resultat.

"Att tänja på gränserna för medicinsk forskning kan vara utmanande. Ibland är idéerna så nya att vi måste ompröva de experimentella metoderna vi använder för att testa dem", säger Gang Fang, Ph.D., docent i genetik och genomvetenskap vid Icahn berget Sinai. "I den här studien utvecklade vi en ny metod för att effektivt mäta detta DNA-märke i en mängd olika arter och celltyper. Vi hoppas att detta kommer att hjälpa forskare att avslöja de många roller dessa processer kan spela i evolution och mänskliga sjukdomar."

Studien fokuserade på DNA-adeninmetylering, en biokemisk reaktion som binder en kemikalie, en så kallad metylgrupp, till en adenin, en av de fyra byggstensmolekyler som används för att konstruera långa DNA-strängar och koda gener. Detta kan "epigenetiskt" aktivera eller tysta gener utan att faktiskt ändra DNA-sekvenser. Det är till exempel känt att adeninmetylering spelar en avgörande roll för hur vissa bakterier försvarar sig mot virus.

For decades, scientists thought that adenine methylation strictly happened in bacteria whereas human and other non-bacterial cells relied on the methylation of a different building block—cytosine—to regulate genes. Then, starting around 2015, this view changed. Scientists spotted high levels of adenine methylation in plant, fly, mouse, and human cells, suggesting a wider role for the reaction throughout evolution.

However, the scientists who performed these initial experiments faced difficult trade-offs. Some used techniques that can precisely measure adenine methylation levels from any cell type but do not have the capacity to identify which cell each piece of DNA came from, while others relied on methods that can spot methylation in different cell types but may overestimate reaction levels.

In this study, Dr. Fang's team developed a method called 6mASCOPE which overcomes these trade-offs. In it, DNA is extracted from a sample of tissue or cells and chopped up into short strands by proteins called enzymes. The strands are placed into microscopic wells and treated with enzymes that make new copies of each strand. An advanced sequencing machine then measures in real time the rate at which each nucleotide building block is added to a new strand. Methylated adenines slightly delay this process. The results are then fed into a machine learning algorithm which the researchers trained to estimate methylation levels from the sequencing data.

"The DNA sequences allowed us to identify which cells—human or bacterial—methylation occurred in while the machine learning model quantified the levels of methylation in each species separately," said Dr. Fang,

Initial experiments on simple, single-cell organisms, such as green algae, suggested that the 6mASCOPE method was effective in that it could detect differences between two organisms that both had high levels of adenine methylation.

The method also appeared to be effective at quantifying adenine methylation in complex organisms. For example, previous studies had suggested that high levels of methylation may play a role in the early growth of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and of the flowering weed Arabidopsis thaliana . In this study, the researchers found that these high levels of methylation were mostly the result of contaminating bacterial DNA. In reality, the fly and the plant DNA from these experiments only had trace amounts of methylation.

Likewise, experiments on human cells suggested that methylation occurs at very low levels in both healthy and disease conditions. Immune cell DNA obtained from patient blood samples had only trace amounts of methylation.

Similar results were also seen with DNA isolated from glioblastoma brain tumor samples. This result was different than a previous study, which reported much higher levels of adenine methylation in tumor cells. However, as the authors note, more research may be needed to determine how much of this discrepancy may be due to differences in tumor subtypes as well as other potential sources of methylation.

Finally, the researchers found that plasmid DNA, a tool that scientists use regularly to manipulate genes, may be contaminated with high levels of methylation that originated from bacteria, suggesting this DNA could be a source of contamination in future experiments.

"Our results show that the manner in which adenine methylation is measured can have profound effects on the result of an experiment. We do not mean to exclude the possibility that some human tissues or disease subtypes may have highly abundant DNA adenine methylation, but we do hope 6mASCOPE will help scientists fully investigate this issue by excluding the bias from bacterial contamination," said Dr. Gang. "To help with this we have made the 6mASCOPE analysis software and a detailed operating manual widely available to other researchers."