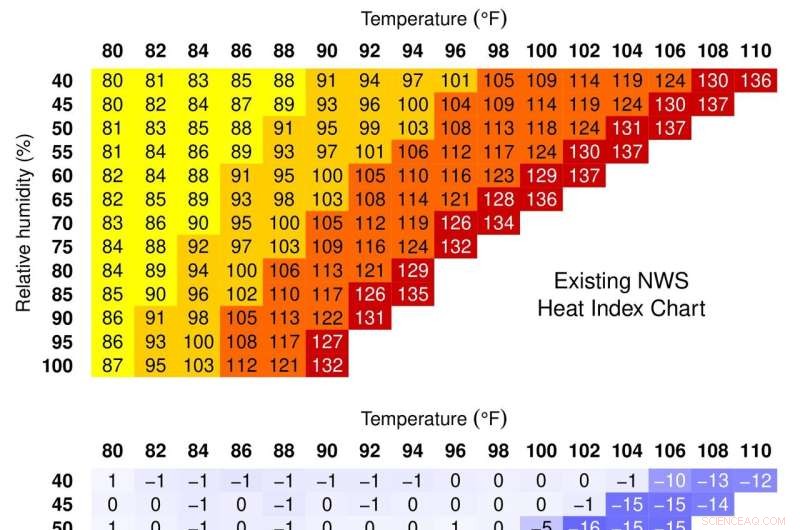

Den länge använda Heat Index-tabellen (överst) underskattar den skenbara temperaturen för de mest extrema värme- och fuktförhållanden som förekommer idag (mitten). Den korrigerade versionen (nederst) är korrekt över hela området av temperaturer och luftfuktigheter som människor kommer att stöta på vid klimatförändringar. Kredit:David Romps och Yi-Chuan Lu, UC Berkeley

Om du har tittat på värmeindex under sommarens klibbiga värmeböljor och tänkt "det känns visst varmare", kan du ha rätt.

En analys av klimatforskare vid University of California, Berkeley, visar att den skenbara temperaturen, eller värmeindexet, beräknat av meteorologer och National Weather Service (NWS) för att indikera hur varmt det känns – med hänsyn till luftfuktigheten – underskattar den upplevda temperatur under de mest svällande dagarna vi nu upplever, ibland mer än 20 grader Fahrenheit.

Fyndet har implikationer för dem som lider av dessa värmeböljor, eftersom värmeindex är ett mått på hur kroppen hanterar värme när luftfuktigheten är hög, och svettning blir mindre effektiv för att kyla ner oss. Svettning och rodnad – där blod avleds till kapillärer nära huden för att avleda värme – och att fälla kläder är de viktigaste sätten att anpassa sig till varma temperaturer.

Ett högre värmeindex innebär att människokroppen är mer stressad under dessa värmeböljor än vad folkhälsotjänstemän kanske inser, säger forskarna. NWS anser för närvarande att ett värmeindex över 103 är farligt och över 125 som extremt farligt.

"För det mesta är värmeindexet som National Weather Service ger dig precis rätt värde. Det är bara i dessa extrema fall där de får fel nummer", säger David Romps, professor i jord och planeter från UC Berkeley vetenskap. "Där det spelar roll är när du börjar kartlägga värmeindexet tillbaka till fysiologiska tillstånd och du inser, åh, dessa människor stressas till ett tillstånd av mycket förhöjt hudblodflöde där kroppen är nära att få slut på knep för att kompensera för den här typen av värme och luftfuktighet. Så vi är närmare den kanten än vi trodde att vi var tidigare."

Romps och doktoranden Yi-Chuan Lu detaljerade sin analys i en artikel som godkänts av tidskriften Environmental Research Letters och publicerades online 12 augusti.

Värmeindexet togs fram 1979 av en textilfysiker, Robert Steadman, som skapade enkla ekvationer för att beräkna vad han kallade den relativa "sultriness" av varma och fuktiga, såväl som varma och torra, förhållanden under sommaren. Han såg det som ett komplement till den vindkylningsfaktor som vanligtvis används på vintern för att uppskatta hur kallt det känns.

Hans modell tog hänsyn till hur människor reglerar sin inre temperatur för att uppnå termisk komfort under olika yttre förhållanden av temperatur och luftfuktighet – genom att medvetet ändra tjockleken på kläder eller omedvetet justera andning, svett och blodflöde från kroppens kärna till huden.

In his model, the apparent temperature under ideal conditions—an average-sized person in the shade with unlimited water—is how hot someone would feel if the relative humidity were at a comfortable level, which Steadman took to be a vapor pressure of 1,600 pascals.

For example, at 70% relative humidity and 68 F—which is often taken as average humidity and temperature—a person would feel like it's 68 F. But at the same humidity and 86 F, it would feel like 94 F.

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the United States, including by the NWS, as a useful indicator of people's comfort. But Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88 F or below 59 F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90 F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast.

To account for these gaps in Steadman's chart, meteorologists extrapolated into these areas to get numbers, Romps said, that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology.

"There's no scientific basis for these numbers," Romps said.

He and Lu set out to extend Steadman's work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.

"The original table had a very short range of temperature and humidity and then a blank region where Steadman said the human model failed," Lu said. "Steadman had the right physics. Our aim was to extend it to all temperatures so that we have a more accurate formula."

One condition under which Steadman's model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible.

"It was at that point where this model seems to break, but it's just the model telling him, hey, let sweat drip off the skin. That's all it was," Romps said. "Just let the sweat drop off the skin."

That and a few other tweaks to Steadman's equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, Romps said, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes outside those Steadman originally calculated. When he originally published his apparent temperature scale, he considered these regimes too rare to worry about, but high temperatures and humidities are becoming increasingly common because of climate change.

Romps and Lu had published the revised heat index equation earlier this year. In the most recent paper, they apply the extended heat index to the top 100 heat waves that occurred between 1984 and 2020. The researchers find mostly minor disagreements with what the NWS reported at the time, but also some extreme situations where the NWS heat index was way off.

One surprise was that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heat waves over that time period were in the Midwest—mostly in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri—not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. The largest discrepancies between the NWS heat index and the extended heat index were seen in a wide swath, from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana.

During the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago, for example, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135 F, when it actually felt like 154 F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141 F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124 F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heat wave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

"I'm no physiologist, but a lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot," Romps said. "Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you're pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin's temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heat waves."

Physiologically, the body starts going haywire when the skin temperature rises to equal the body's core temperature, typically taken as 98.6 F. After that, the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107 F—the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200 F.

Luckily, humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases, so Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme—though still deadly—conditions are nevertheless becoming common around the globe.

"A 200 F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable," Romps said. "But now that we've got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the United States and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at." + Utforska vidare