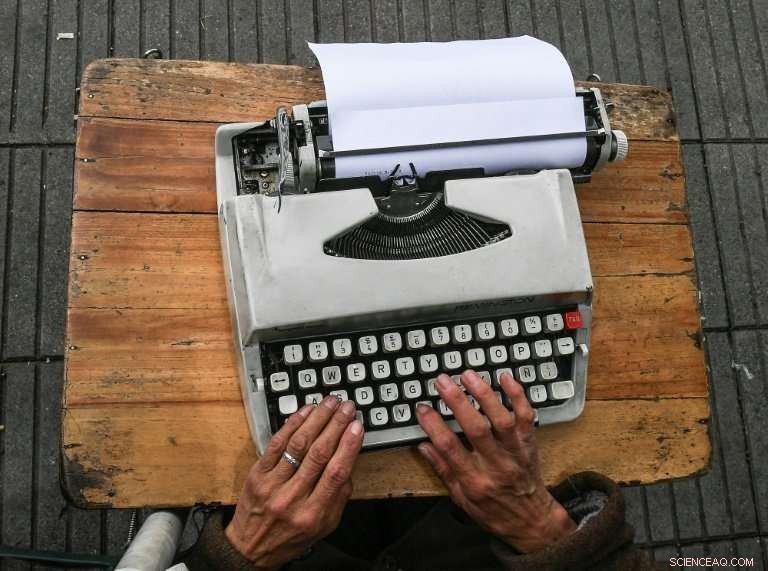

Colombias gatumedlemmar arbetar i det fria med sina skrivmaskiner uppe på ett litet bord framför dem

Inför 1 maj, AFP -reportrar, video- och fototeam talade med män och kvinnor runt om i världen vars jobb blir allt mer sällsynta, särskilt när tekniken förvandlar samhällen.

Bogotas sista gatukontorister

Infoga ett tomt ark i hennes Remington Sperry, Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez börjar skriva. En av Bogotas gatukontorister, hon har spenderat de senaste 40 åren med att skriva upp otaliga tusentals dokument.

63 år, hon är den enda kvinnan bland gatukontoristerna som har ställt upp sina små bord på trottoaren utanför ett modernt kontorshus i Bogotá.

I kostymer men inga slipsar, författarna arbetar utomhus under ett parasoll, sitter på en plaststol med skrivmaskinen på knäna.

Det var en gång, dessa kontorister spelade en väsentlig roll - med offentliga gärningar, skattehandlingar och kontrakt som alla passerar genom deras händer.

Pinilla de Gomez lärde sig yrket av sin man när de anlände till den colombianska huvudstaden på 1960 -talet. Han hade en gård "men gerillan tog den av honom, " hon säger.

"I Bogota, han sa till mig att jag skulle lära mig att skriva ... och stava. Han lärde mig (jobbet) och sedan dog han. "

Cesar Diaz, nu 68, är stolt över att vara pionjär inom en handel som har blivit en ”fristad” för pensionärer som vill fylla på sina månatliga bidrag.

Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez, 63, har arbetat som gatukontor i Bogotá i cirka 40 år

De arbetar från måndag till fredag och tjänar mindre än $ 280 vilket är minimilönen.

Tills nu, de har lyckats överleva i stort sett allt - förutom kanske tillkomsten av internet.

"Dessa dagar, en mamma kommer att be sin son att ladda ner ett formulär, fyll i det och skicka det via internet, "erkänner Pinilla de Gomez.

"Det skruvar verkligen upp saker för oss."

- Bilder av Luis Acosta. Video av Juan Restrepo

Tvättmän, deras handel försvinner som tvål i vatten

Delia Veloz händer har nästan tappat sina fingeravtryck från den ständiga rytmiska rörelsen att gnugga smutsiga kläder mot grova stenar vid en gammal offentlig tvättstuga i Quito.

Med en mopp av lockiga grå lockar, den här 74-åringen är en av få personer kvar i Ecuador som fortfarande utövar en gammal tvättmästares gamla och krävande arbete-en handel som blir allt mer sällsynt på grund av den utbredda användningen av hushållstvättmaskiner.

Wu Chi-kai böjer glasrör dammade inuti med fluorescerande pulver i form över en kraftfull gasbrännare

"Jag gillar inte tvättmaskiner, de tvättar inte särskilt bra. Du kan skrubba saker bättre för hand, "Veloz säger stolt till AFP när hon häller en burk med frysande vatten från Anderna över en jacka.

I mer än fem decennier har hon arbetat på Ermita, en offentlig tvättstuga i Quitos koloniala centrum med sin rektangulära sten, tank med vatten och olika trådar för att hänga ut saker för att torka.

För varje 12 klädesplagg, hon tjänar 1,50 dollar (1,20 euro) från sina allt få kunder - mestadels de som inte har en tvättmaskin eller som föredrar att saker tvättas för hand.

På en bra dag, hon kan tjäna mellan $ 3 och $ 6.

I Quito, det finns fortfarande minst fem offentliga tvättstugor som byggdes under 1900 -talets första hälft.

Det finns också de som kommer för att använda tvätten för att tvätta sina egna kläder eller de som tillhör sina arbetsgivare - för vilka det inte finns någon avgift.

Och en gång i månaden, de samlas alla för att hålla lokalerna snygga och städade.

- Bilder av Rodrigo Buendia

Neon har kommit att definiera stadslandskapet i Hong Kong, med enorma blinkande skyltar som sticker ut horisontellt från sidorna av byggnader

Waterboys börjar torka

Bristen på rinnande vatten i Kenyas fattigaste stadsdelar har, under de senaste 18 åren, betydde ett liv för Samson Muli, en vattenförsäljare i Kaira -slummen i Nairobi.

"När jag växte upp ville jag bli en affärsman, "säger den 42-årige tvåbarnspappan, som levererar vatten till slaktare, fiskhandlare och restauranger på den fullsatta Kenyatta -marknaden.

Klädd i en tunn dammrock Muli använder en slang för att fylla sin serie cylindriska 20-liters jerrycans med vatten från tre fristående 10, 000 liters tankar. Han lastar 15 i taget på en vagn, och transporterar dem till sina kunder.

The margins are tiny—Muli buys water at five shillings ($0.05) a can and sells for 15—but it can add up to 1, 000 shillings a day, enough to make a difference.

"This job has changed my life because my children are able to go to school and I am able to afford to pay school fees for them, " han säger.

But Kenya's gradual development and the spreading provision of basic infrastructure, including piped water, means Muli's profitable days are numbered.

— Pictures by Simon Maina. Video by Raphael Ambasu

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes

Rickshaw pullers fade from India's streets

Mohammad Maqbool Ansari puffs and sweats as he pulls his rickshaw through Kolkata's teeming streets, a veteran of a gruelling trade long outlawed in most parts of the world and slowly fading from India too.

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life, but Ansari is among a dying breed still eking a living from this back-breaking labour.

The 62-year-old has been pulling rickshaws for nearly four decades, hauling cargo and passengers by hand in drenching monsoon rains and stifling heat that envelops India's heaving eastern metropolis.

Their numbers are declining as pulled rickshaws are relegated to history, usurped by tuk tuks, Kolkata's famous yellow taxis and modern conveniences like Uber.

Ansari cannot imagine life for Kolkata's thousands of rickshaw-wallahs if the job ceased to exist.

"If we don't do it, how will we survive? We can't read or write. We can't do any other work. Once you start, that's it. This is our life, " he tells AFP.

Sweating profusely on a searing-hot day, his singlet soaked and face dripping, Ansari skilfully weaved his rickshaw through crowded markets and bumper to bumper traffic.

Venezuelan darkroom technician Rodrigo Benavides refuses to go digital

Wearing simple shoes and a chequered sarong, the only real giveaway of his age is a long beard, snow white and frizzy, and a face weathered from a lifetime plying this trade.

Twenty minutes later, he stops, wiping his face on a rag. The passenger offers him a glass of water—a rare blessing—and hands a bill over.

"When it's hot, for a trip that costs 50 rupees ($0.75) I'll ask for an extra 10 rupees. Some will give, some don't, " han säger.

"But I'm happy with being a rickshaw puller. I'm able to feed myself and my family."

— Pictures by Dibyangshu Sarkar. Video by Atish Patel

Hong Kong's neon nostalgia

Neon sign maker Wu Chi-kai is one of the last remaining craftsmen of his kind in Hong Kong, a city where darkness never really falls thanks to the 24-hour glow of myriad lights.

During his 30 years in the business, neon came to define the urban landscape, huge flashing signs protruding horizontally from the sides of buildings, advertising everything from restaurants to mahjong parlours.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography does not exist

But with the growing popularity of brighter LED lights, seen as easier to maintain and more environmentally friendly, and government orders to remove some vintage signs deemed dangerous, the demand for specialists like Chi-kai has dimmed.

Despite a waning client-base, the 50-year-old continues in the trade, working with glass tubes dusted inside with fluorescent powder and containing various gases including neon or argon, as well as mercury, to create different colours.

He bends them into shape over a powerful gas burner at a scorching 1, 000 degrees Celsius.

"Being able to twist straight glass materials into the shape I want, and later to make it glow—it's quite fun, säger han till AFP, though it is not without risks.

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes.

"The painful experiences are the memorable ones, " he adds philosophically.

His father used to scale Hong Kong's famous bamboo scaffolding while installing neon signs across the city.

Believing the installation work too dangerous for his son, he instead encouraged him to learn to make the signs as a teenager. Chi-kai became one of only around 30 masters of the craft in Hong Kong, even in neon's heyday.

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints

Although demand is now significantly lower than at neon's peak in the 1980s, han säger, there has been renewed interest and nostalgia for its gentler glow, immortalised in the atmospheric movies of award-winning Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai.

Some of Chi-kai's clients are now requesting pieces for indoor decoration.

"I've been working with neon lights all my life. I can't think of anything else I'd be better suited for, " han säger.

— Pictures by Philip Fong. Video by Diana Chan

Developing film as if digital didn't exist

With an ancient 50-year-old Olympus camera and an enlarger that he bought in 1980, Venezuelan photographer Rodrigo Benavides works his "magic" inside a tiny improvised darkroom at home.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography doesn't exist.

"Doesn't interest me at all, " han säger.

Once upon a time, these clerks played an essential role—with public deeds, tax documents and contracts all passing through their hands

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints. And it still fascinates him every time as the image slowly emerges on coming in to contact with the chemicals.

"I have always tried to be economical with my resources, always have done, always will do, " han säger, extolling the wonders of his Olympus 35 SP which uses a reel of film, doesn't need batteries and is completely manual.

Born in Caracas 58 years ago, he still remembers the excitement when, at the age of 19, he bought the enlarger in London.

And it was there that he became a keen follower of Group f/64, an influential movement of photographers who championed sharp-focused, unretouched images of natural subjects.

He thinks technology has "upended" photography, turning it into a work of "fiction."

"We have become desensitised to reality, which is much more interesting than fiction, " han säger.

Some 400 of his pictures taken over 30 years have been compiled into a book on the Venezuelan plains. Others are stacked up in his living room, forming a towering pile, some two meters high.

"They are like my children, " says Benavides, who describes himself as a documentary photographer practising a trade on the verge of extinction.

Delia Veloz, 74, is one of the few people left in Ecuador who still practises the ancient and demanding work of a washerwoman

Washerwomen rub dirty clothes against rough stones at an old public laundry in Quito

In Quito, there are still at least five public laundries which were built in the first half of the 20th century

The lack of running water in Kenya's poorest neighbourhoods has meant a living for Samson Muli, a water seller in Nairobi's Kibera slum

Waterboys supply water to butchers, fishmongers and restaurants in the crowded Kenyatta market

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life

Mohammad Ashgar is one of the remaining Indian rickshaw pullers undertaking the gruelling trade

© 2018 AFP