En tropisk regnskog i Sydamerika. Kredit:Shutterstock/BorneoRimbawan

En morgon 2009, Jag satt på en knarrande buss som slingrade sig uppför en bergssida i centrala Costa Rica, yr i huvudet av dieselångor när jag tog tag i mina många resväskor. De innehöll tusentals provrör och provflaskor, en tandborste, en vattentät anteckningsbok och två klädbyten.

Jag var på väg till La Selva biologiska station, där jag skulle tillbringa flera månader med att studera det våta, låglandsregnskogens svar på allt vanligare torka. På båda sidor om den smala motorvägen, träd blödde in i dimman som akvareller till papper, ger intrycket av en oändlig urskog badad i moln.

När jag tittade ut genom fönstret på det imponerande landskapet, Jag undrade hur jag någonsin kunde hoppas på att förstå ett så komplext landskap. Jag visste att tusentals forskare över hela världen brottades med samma frågor, försöker förstå tropiska skogars öde i en snabbt föränderlig värld.

Vårt samhälle kräver så mycket av dessa ömtåliga ekosystem, som kontrollerar tillgången på sötvatten för miljontals människor och är hem för två tredjedelar av jordens biologiska mångfald på jorden. Och alltmer, vi har ställt ett nytt krav på dessa skogar – för att rädda oss från klimatförändringar som orsakas av människor.

Växter absorberar CO 2 från atmosfären, förvandla det till löv, ved och rötter. Detta vardagliga mirakel har väckt förhoppningar om att växter – särskilt snabbväxande tropiska träd – kan fungera som en naturlig broms mot klimatförändringarna, fångar upp mycket av CO 2 släpps ut vid förbränning av fossila bränslen. Över hela världen, regeringar, företag och välgörenhetsorganisationer för bevarande har lovat att bevara eller plantera ett enormt antal träd.

Men faktum är att det inte finns tillräckligt med träd för att kompensera samhällets koldioxidutsläpp – och det kommer det aldrig att bli. Jag genomförde nyligen en genomgång av tillgänglig vetenskaplig litteratur för att bedöma hur mycket kol skogar skulle kunna absorbera. Om vi absolut maximerade mängden vegetation som all mark på jorden kunde hålla, vi skulle binda tillräckligt med kol för att kompensera för cirka tio års utsläpp av växthusgaser i nuvarande takt. Efter det, det kunde inte ske någon ytterligare ökning av kolavskiljningen.

Ändå är vår arts öde oupplösligt kopplat till skogarnas överlevnad och den biologiska mångfalden de innehåller. Genom att skynda sig att plantera miljontals träd för kolavskiljning, kan vi oavsiktligt skada just de skogsfastigheter som gör dem så viktiga för vårt välbefinnande? För att svara på denna fråga, vi behöver inte bara tänka på hur växter absorberar CO 2 , men också hur de ger den robusta gröna grunden för ekosystem på land.

Hur växter bekämpar klimatförändringar

Växter omvandlar CO 2 gas till enkla sockerarter i en process som kallas fotosyntes. Dessa sockerarter används sedan för att bygga upp växternas levande kroppar. Om det fångade kolet hamnar i trä, den kan låsas bort från atmosfären i många decennier. När växter dör, deras vävnader genomgår förfall och införlivas i jorden.

Bonnie Waring bedriver forskning vid La Selva biologiska station, Costa Rica, 2011. Författare tillhandahålls

Även om denna process naturligt frigör CO 2 genom andning (eller andning) av mikrober som bryter ner döda organismer, en del av växtens kol kan förbli under jord i årtionden eller till och med århundraden. Tillsammans, landväxter och jordar rymmer cirka 2, 500 gigaton kol – ungefär tre gånger mer än vad som finns i atmosfären.

Eftersom växter (särskilt träd) är så utmärkta naturliga lagerhus för kol, Det är vettigt att ett ökat överflöd av växter över hela världen skulle kunna dra ner koldioxid i atmosfären 2 koncentrationer.

Växter behöver fyra grundläggande ingredienser för att växa:ljus, CO 2 , vatten och näringsämnen (som kväve och fosfor, samma ämnen som finns i växtgödsel). Tusentals forskare över hela världen studerar hur växttillväxt varierar i förhållande till dessa fyra ingredienser, för att förutsäga hur vegetationen kommer att reagera på klimatförändringarna.

Detta är en förvånansvärt utmanande uppgift, med tanke på att människor samtidigt modifierar så många aspekter av den naturliga miljön genom att värma upp jordklotet, ändra nederbördsmönster, hugga stora skogsområden i små fragment och introducera främmande arter där de inte hör hemma. Det finns också över 350, 000 arter av blommande växter på land och var och en svarar på miljöutmaningar på unika sätt.

På grund av de komplicerade sätt på vilka människor förändrar planeten, Det finns en hel del vetenskaplig debatt om den exakta mängden kol som växter kan absorbera från atmosfären. Men forskarna är eniga om att markekosystem har en begränsad kapacitet att ta upp kol.

Om vi ser till att träd har tillräckligt med vatten att dricka, skogar kommer att växa sig höga och frodiga, skapa skuggiga baldakiner som svälter mindre träd av ljus. Om vi ökar koncentrationen av CO 2 i luften, växter kommer ivrigt att absorbera det - tills de inte längre kan extrahera tillräckligt med gödsel från jorden för att tillgodose deras behov. Precis som en bagare bakar en tårta, växter kräver CO 2 , kväve och fosfor i särskilda förhållanden, efter ett specifikt recept för livet.

Som ett erkännande av dessa grundläggande begränsningar, forskare uppskattar att jordens markekosystem kan hålla tillräckligt med extra vegetation för att absorbera mellan 40 och 100 gigaton kol från atmosfären. När denna ytterligare tillväxt har uppnåtts (en process som kommer att ta ett antal decennier), det finns ingen kapacitet för ytterligare kollagring på land.

Men vårt samhälle häller för närvarande CO 2 ut i atmosfären med en hastighet av tio gigaton kol per år. Naturliga processer kommer att kämpa för att hålla jämna steg med störtfloden av växthusgaser som genereras av den globala ekonomin. Till exempel, Jag beräknade att en enstaka passagerare på en flygning tur och retur från Melbourne till New York kommer att släppa ut ungefär dubbelt så mycket kol (1600 kg C) som det finns i en ek med en halvmeter i diameter (750 kg C).

Löv i mikroskop:stomin som reglerar syre och koldioxid kan ses. Kredit:Shutterstock/Barbol

Fara och löfte

Trots alla dessa välkända fysiska begränsningar för växttillväxt, det finns ett växande antal storskaliga ansträngningar för att öka vegetationstäcket för att mildra klimatkrisen – en så kallad "naturbaserad" klimatlösning. De allra flesta av dessa insatser fokuserar på att skydda eller expandera skogar, eftersom träd innehåller många gånger mer biomassa än buskar eller gräs och därför representerar större kolavskiljningspotential.

Ändå kan grundläggande missförstånd om kolavskiljning av markekosystem få förödande konsekvenser, vilket leder till förluster av biologisk mångfald och en ökning av koldioxid 2 koncentrationer. Detta verkar vara en paradox – hur kan plantering av träd påverka miljön negativt?

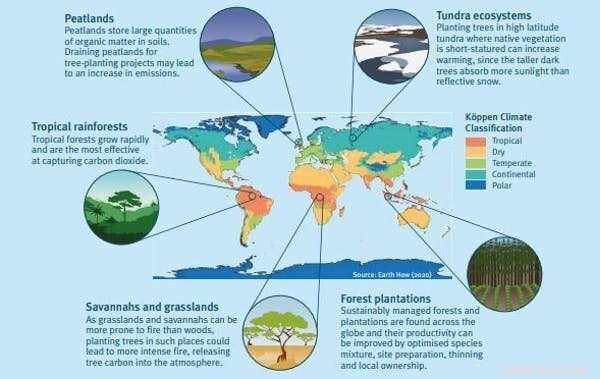

Svaret ligger i den subtila komplexiteten av kolavskiljning i naturliga ekosystem. För att undvika miljöskador, vi måste avstå från att anlägga skogar där de naturligt inte hör hemma, undvika "perversa incitament" att avverka befintlig skog för att plantera nya träd, och överväga hur plantor som planterats idag kan klara sig under de kommande decennierna.

Innan någon utvidgning av skogshabitat genomförs, vi måste se till att träd planteras på rätt plats eftersom inte alla ekosystem på land kan eller bör stödja träd. Att plantera träd i ekosystem som normalt domineras av andra typer av vegetation leder ofta inte till långvarig kolbindning.

Ett särskilt belysande exempel kommer från skotska torvmarker - stora delar av land där den låglänta vegetationen (mest mossor och gräs) växer i konstant fuktig, fuktig mark. Eftersom nedbrytningen är mycket långsam i de sura och vattendränkta jordarna, döda växter samlas under mycket långa tidsperioder, skapa torv. Det är inte bara växtligheten som bevaras:torvmossar mumifierar också så kallade "mosskroppar" - de nästan intakta resterna av män och kvinnor som dog för årtusenden sedan. Faktiskt, Brittiska torvmarker innehåller 20 gånger mer kol än vad som finns i landets skogar.

Men i slutet av 1900-talet, några skotska myrar dränerades för trädplantering. Torkning av jorden gjorde att trädplantor kunde etablera sig, men fick också torvens förfall att påskyndas. Ekologen Nina Friggens och hennes kollegor vid University of Exeter uppskattade att nedbrytningen av torvtorv frigjorde mer kol än vad de växande träden kunde ta upp. Klart, torvmarker kan bäst skydda klimatet när de lämnas åt sig själva.

Detsamma gäller gräsmarker och savanner, där bränder är en naturlig del av landskapet och ofta bränner träd som planteras där de inte hör hemma. Denna princip gäller även för arktiska tundra, där den inhemska vegetationen är täckt av snö hela vintern, reflekterar ljus och värme tillbaka till rymden. Planterar högt, mörkbladiga träd i dessa områden kan öka absorptionen av värmeenergi, och leda till lokal uppvärmning.

Men även att plantera träd i skogsmiljöer kan leda till negativa miljöeffekter. Ur perspektivet av både kolbindning och biologisk mångfald, alla skogar är inte lika – naturligt etablerade skogar innehåller fler arter av växter och djur än plantageskogar. De innehåller ofta mer kol, för. Men politik som syftar till att främja trädplantering kan oavsiktligt stimulera till avskogning av väletablerade naturliga livsmiljöer.

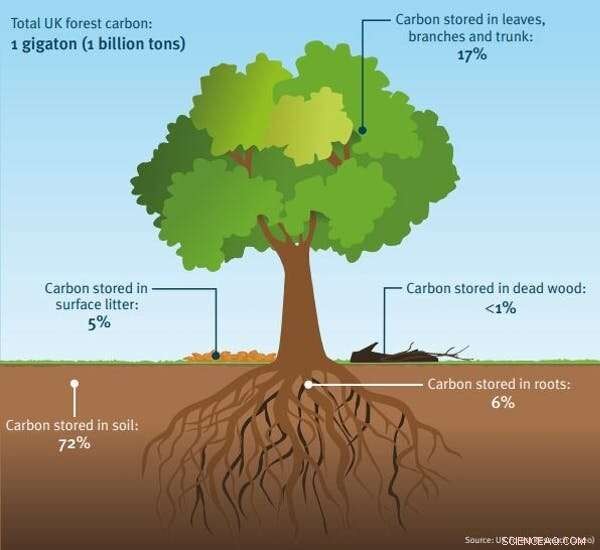

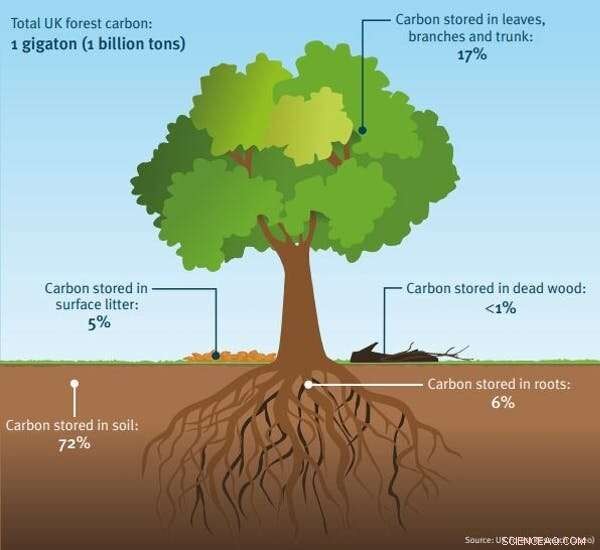

Where carbon is stored in a typical temperate forest in the UK. Credit:UK Forest Research, CC BY

A recent high-profile example concerns the Mexican government's Sembrando Vida program, which provides direct payments to landowners for planting trees. Problemet? Many rural landowners cut down well established older forest to plant seedlings. This decision, while quite sensible from an economic point of view, has resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of hectares of mature forest.

This example demonstrates the risks of a narrow focus on trees as carbon absorption machines. Many well meaning organizations seek to plant the trees which grow the fastest, as this theoretically means a higher rate of CO 2 "drawdown" from the atmosphere.

Yet from a climate perspective, what matters is not how quickly a tree can grow, but how much carbon it contains at maturity, and how long that carbon resides in the ecosystem. As a forest ages, it reaches what ecologists call a "steady state"—this is when the amount of carbon absorbed by the trees each year is perfectly balanced by the CO 2 released through the breathing of the plants themselves and the trillions of decomposer microbes underground.

This phenomenon has led to an erroneous perception that old forests are not useful for climate mitigation because they are no longer growing rapidly and sequestering additional CO 2 . The misguided "solution" to the issue is to prioritize tree planting ahead of the conservation of already established forests. This is analogous to draining a bathtub so that the tap can be turned on full blast:the flow of water from the tap is greater than it was before—but the total capacity of the bath hasn't changed. Mature forests are like bathtubs full of carbon. They are making an important contribution to the large, but finite, quantity of carbon that can be locked away on land, and there is little to be gained by disturbing them.

What about situations where fast growing forests are cut down every few decades and replanted, with the extracted wood used for other climate-fighting purposes? While harvested wood can be a very good carbon store if it ends up in long lived products (like houses or other buildings), surprisingly little timber is used in this way.

Liknande, burning wood as a source of biofuel may have a positive climate impact if this reduces total consumption of fossil fuels. But forests managed as biofuel plantations provide little in the way of protection for biodiversity and some research questions the benefits of biofuels for the climate in the first place.

Fertilize a whole forest

Scientific estimates of carbon capture in land ecosystems depend on how those systems respond to the mounting challenges they will face in the coming decades. All forests on Earth—even the most pristine—are vulnerable to warming, changes in rainfall, increasingly severe wildfires and pollutants that drift through the Earth's atmospheric currents.

Some of these pollutants, dock, contain lots of nitrogen (plant fertilizer) which could potentially give the global forest a growth boost. By producing massive quantities of agricultural chemicals and burning fossil fuels, humans have massively increased the amount of "reactive" nitrogen available for plant use. Some of this nitrogen is dissolved in rainwater and reaches the forest floor, where it can stimulate tree growth in some areas.

Implications of large-scale tree planting in various climatic zones and ecosystems. Credit:Stacey McCormack/Köppen climate classification, Författare tillhandahålls

As a young researcher fresh out of graduate school, I wondered whether a type of under-studied ecosystem, known as seasonally dry tropical forest, might be particularly responsive to this effect. There was only one way to find out:I would need to fertilize a whole forest.

Working with my postdoctoral adviser, the ecologist Jennifer Powers, and expert botanist Daniel Pérez Avilez, I outlined an area of the forest about as big as two football fields and divided it into 16 plots, which were randomly assigned to different fertilizer treatments. For the next three years (2015-2017) the plots became among the most intensively studied forest fragments on Earth. We measured the growth of each individual tree trunk with specialised, hand-built instruments called dendrometers.

We used baskets to catch the dead leaves that fell from the trees and installed mesh bags in the ground to track the growth of roots, which were painstakingly washed free of soil and weighed. The most challenging aspect of the experiment was the application of the fertilizers themselves, which took place three times a year. Wearing raincoats and goggles to protect our skin against the caustic chemicals, we hauled back-mounted sprayers into the dense forest, ensuring the chemicals were evenly applied to the forest floor while we sweated under our rubber coats.

Tyvärr, our gear didn't provide any protection against angry wasps, whose nests were often concealed in overhanging branches. Men, our efforts were worth it. Efter tre år, we could calculate all the leaves, wood and roots produced in each plot and assess carbon captured over the study period. We found that most trees in the forest didn't benefit from the fertilizers—instead, growth was strongly tied to the amount of rainfall in a given year.

This suggests that nitrogen pollution won't boost tree growth in these forests as long as droughts continue to intensify. To make the same prediction for other forest types (wetter or drier, younger or older, warmer or cooler) such studies will need to be repeated, adding to the library of knowledge developed through similar experiments over the decades. Yet researchers are in a race against time. Experiments like this are slow, painstaking, sometimes backbreaking work and humans are changing the face of the planet faster than the scientific community can respond.

Humans need healthy forests

Supporting natural ecosystems is an important tool in the arsenal of strategies we will need to combat climate change. But land ecosystems will never be able to absorb the quantity of carbon released by fossil fuel burning. Rather than be lulled into false complacency by tree planting schemes, we need to cut off emissions at their source and search for additional strategies to remove the carbon that has already accumulated in the atmosphere.

Does this mean that current campaigns to protect and expand forest are a poor idea? Emphatically not. The protection and expansion of natural habitat, particularly forests, is absolutely vital to ensure the health of our planet. Forests in temperate and tropical zones contain eight out of every ten species on land, yet they are under increasing threat. Nearly half of our planet's habitable land is devoted to agriculture, and forest clearing for cropland or pasture is continuing apace.

Under tiden, the atmospheric mayhem caused by climate change is intensifying wildfires, worsening droughts and systematically heating the planet, posing an escalating threat to forests and the wildlife they support. What does that mean for our species? Again and again, researchers have demonstrated strong links between biodiversity and so-called "ecosystem services"—the multitude of benefits the natural world provides to humanity.

Dendrometer devices wrapped around tree trunks to measure growth. Författare tillhandahålls

Carbon capture is just one ecosystem service in an incalculably long list. Biodiverse ecosystems provide a dizzying array of pharmaceutically active compounds that inspire the creation of new drugs. They provide food security in ways both direct (think of the millions of people whose main source of protein is wild fish) and indirect (for example, a large fraction of crops are pollinated by wild animals).

Natural ecosystems and the millions of species that inhabit them still inspire technological developments that revolutionize human society. Till exempel, take the polymerase chain reaction ("PCR") that allows crime labs to catch criminals and your local pharmacy to provide a COVID test. PCR is only possible because of a special protein synthesized by a humble bacteria that lives in hot springs.

As an ecologist, I worry that a simplistic perspective on the role of forests in climate mitigation will inadvertently lead to their decline. Many tree planting efforts focus on the number of saplings planted or their initial rate of growth—both of which are poor indicators of the forest's ultimate carbon storage capacity and even poorer metric of biodiversity. Mer viktigt, viewing natural ecosystems as "climate solutions" gives the misleading impression that forests can function like an infinitely absorbent mop to clean up the ever increasing flood of human caused CO 2 utsläpp.

Lyckligtvis, many big organizations dedicated to forest expansion are incorporating ecosystem health and biodiversity into their metrics of success. A little over a year ago, I visited an enormous reforestation experiment on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, operated by Plant-for-the-Planet—one of the world's largest tree planting organizations. After realizing the challenges inherent in large scale ecosystem restoration, Plant-for-the-Planet has initiated a series of experiments to understand how different interventions early in a forest's development might improve tree survival.

But that is not all. Led by Director of Science Leland Werden, researchers at the site will study how these same practices can jump-start the recovery of native biodiversity by providing the ideal environment for seeds to germinate and grow as the forest develops. These experiments will also help land managers decide when and where planting trees benefits the ecosystem and where forest regeneration can occur naturally.

Viewing forests as reservoirs for biodiversity, rather than simply storehouses of carbon, complicates decision making and may require shifts in policy. I am all too aware of these challenges. I have spent my entire adult life studying and thinking about the carbon cycle and I too sometimes can't see the forest for the trees. One morning several years ago, I was sitting on the rainforest floor in Costa Rica measuring CO 2 emissions from the soil—a relatively time intensive and solitary process.

As I waited for the measurement to finish, I spotted a strawberry poison dart frog—a tiny, jewel-bright animal the size of my thumb—hopping up the trunk of a nearby tree. Fascinerad, I watched her progress towards a small pool of water held in the leaves of a spiky plant, in which a few tadpoles idly swam. Once the frog reached this miniature aquarium, the tiny tadpoles (her children, as it turned out) vibrated excitedly, while their mother deposited unfertilised eggs for them to eat. As I later learned, frogs of this species (Oophaga pumilio) take very diligent care of their offspring and the mother's long journey would be repeated every day until the tadpoles developed into frogs.

It occurred to me, as I packed up my equipment to return to the lab, that thousands of such small dramas were playing out around me in parallel. Forests are so much more than just carbon stores. They are the unknowably complex green webs that bind together the fates of millions of known species, with millions more still waiting to be discovered. To survive and thrive in a future of dramatic global change, we will have to respect that tangled web and our place in it.

Den här artikeln är återpublicerad från The Conversation under en Creative Commons-licens. Läs originalartikeln.