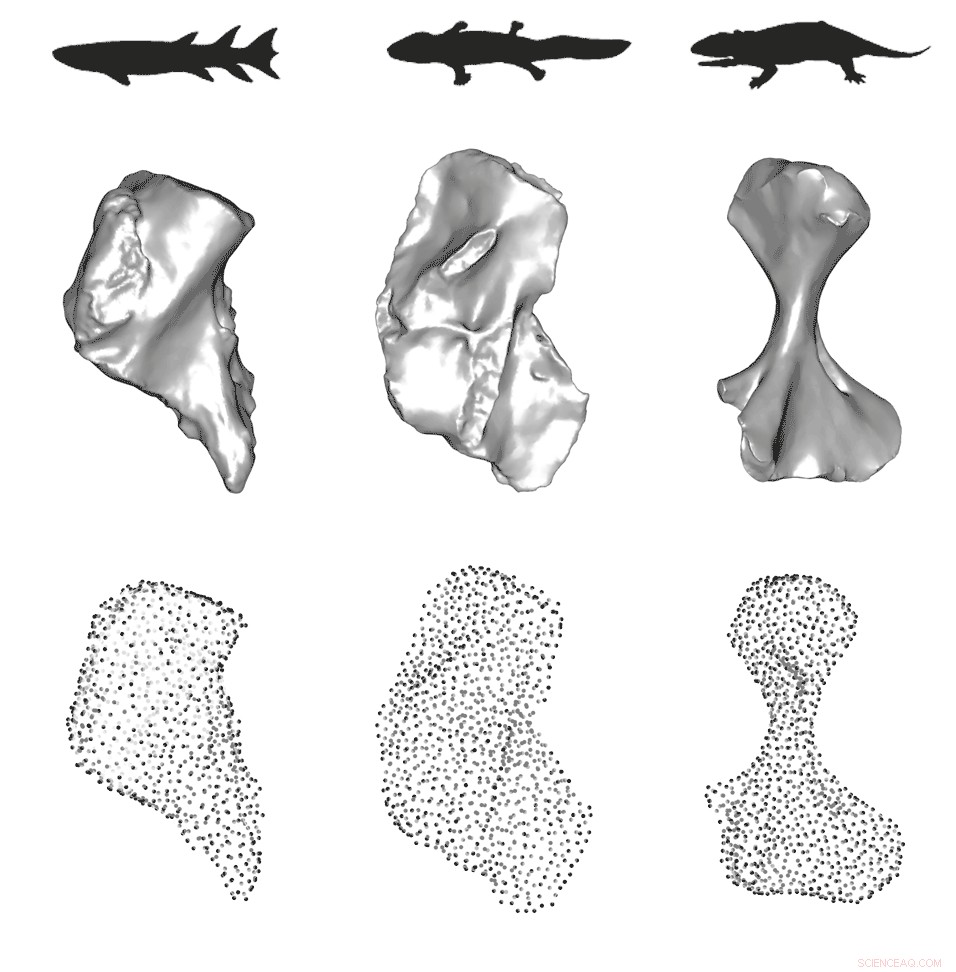

Tre huvudstadier av humerus formar evolutionen:från den blockiga humerus hos vattenfiskar, till den L-formade överarmsbenet hos övergångsfetrapoder, och den vridna överarmsbenet hos terrestra tetrapoder. Kolumner (vänster till höger) =vattenlevande fisk, övergångsfetrapod, och terrestra tetrapod. Rader =Topp:utdöda djursilhuetter; Mellan:3D humerus fossiler; Nederst:landmärken som används för att kvantifiera formen. Kredit:Blake Dickson

Övergången från vatten till land är en av de viktigaste och mest inspirerande stora övergångarna i ryggradsdjurens evolution. Och frågan om hur och när tetrapoder övergick från vatten till land har länge varit en källa till förundran och vetenskaplig debatt.

Tidiga idéer ansåg att uttorkande vattenpölar strandade fisk på land och att vara ute i vattnet gav det selektiva trycket att utveckla fler lemliknande bihang för att gå tillbaka till vattnet. På 1990-talet antydde nyupptäckta exemplar att de första tetrapoderna behöll många akvatiska egenskaper, som gälar och en stjärtfena, och att lemmar kan ha utvecklats i vattnet innan tetrapoder anpassade sig till livet på land. Det finns, dock, fortfarande osäkerhet om när vatten-till-land-övergången ägde rum och hur landlevande tidiga tetrapoder verkligen var.

En tidning publicerad 25 november i Natur tar upp dessa frågor med hjälp av högupplösta fossila data och visar att även om dessa tidiga tetrapoder fortfarande var bundna till vatten och hade vattendrag, de hade också anpassningar som tyder på en viss förmåga att röra sig på land. Fastän, de kanske inte var så bra på att göra det, åtminstone med dagens mått mätt.

Huvudförfattare Blake Dickson, Ph.D. '20 vid institutionen för organisk och evolutionsbiologi vid Harvard University, och seniorförfattaren Stephanie Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Docent vid institutionen för organisk och evolutionsbiologi och curator för ryggradsdjurspaleontologi vid Museum of Comparative Zoology vid Harvard University, undersökt 40 tredimensionella modeller av fossil humeri (överarmsben) från utdöda djur som överbryggar övergången mellan vatten och land.

"Eftersom fossilregistret för övergången till land i fyrfota är så dålig gick vi till en fossilkälla som bättre skulle kunna representera hela övergången hela vägen från att vara en helt vattenlevande fisk till en helt landlevande fyrfot, sa Dickson.

Två tredjedelar av fossilerna kom från de historiska samlingarna på Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology, som kommer från hela världen. För att fylla i de saknade luckorna, Pierce nådde ut till kollegor med nyckelexemplar från Kanada, Skottland, och Australien. Av betydelse för studien var nya fossiler som nyligen upptäckts av medförfattarna Dr. Tim Smithson och professor Jennifer Clack, Universitetet i Cambridge, STORBRITANNIEN, som en del av TW:eed-projektet, ett initiativ utformat för att förstå den tidiga utvecklingen av landgående tetrapoder.

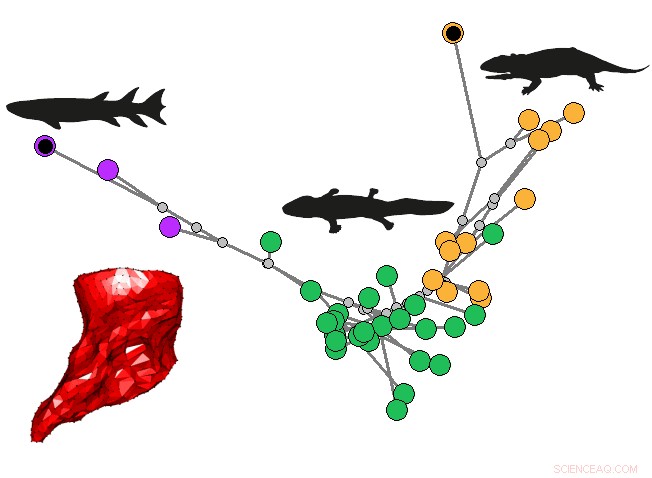

Den evolutionära vägen och formen ändras från en vattenlevande fisk humerus till en terrestra tetrapod humerus. Kredit:Blake Dickson.

Forskarna valde humerusbenet eftersom det inte bara är rikligt och välbevarat i fossilregistret, men det finns också i alla sarkopterygier - en grupp djur som inkluderar coelacant-fiskar, lungfisk, och alla tetrapoder, inklusive alla deras fossila representanter. "Vi förväntade oss att överarmsbenet skulle bära en stark funktionell signal när djuren övergick från att vara en fullt fungerande fisk till att vara helt landlevande tetrapoder, och att vi kunde använda det för att förutsäga när fyrfotsdjur började röra sig på land, " sa Pierce. "Vi fann att jordisk förmåga tycks sammanfalla med lemmens ursprung, vilket är riktigt spännande."

Överarmsbenet förankrar det främre benet på kroppen, är värd för många muskler, och måste motstå mycket stress under extremitetsbaserad rörelse. På grund av detta, den innehåller en hel del kritisk funktionell information relaterad till ett djurs rörelser och ekologi. Researchers have suggested that evolutionary changes in the shape of the humerus bone, from short and squat in fish to more elongate and featured in tetrapods, had important functional implications related to the transition to land locomotion. This idea has rarely been investigated from a quantitative perspective—that is, tills nu.

When Dickson was a second-year graduate student, he became fascinated with applying the theory of quantitative trait modeling to understanding functional evolution, a technique pioneered in a 2016 study led by a team of paleontologists and co-authored by Pierce. Central to quantitative trait modeling is paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson's 1944 concept of the adaptive landscape, a rugged three-dimensional surface with peaks and valleys, like a mountain range. On this landscape, increasing height represents better functional performance and adaptive fitness, and over time it is expected that natural selection will drive populations uphill towards an adaptive peak.

Dickson and Pierce thought they could use this approach to model the tetrapod transition from water to land. They hypothesized that as the humerus changed shape, the adaptive landscape would change too. For instance, fish would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for swimming and terrestrial tetrapods would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for walking on land. "We could then use these landscapes to see if the humerus shape of earlier tetrapods was better adapted for performing in water or on land" said Pierce.

"We started to think about what functional traits would be important to glean from the humerus, " said Dickson. "Which wasn't an easy task as fish fins are very different from tetrapod limbs." In the end, they narrowed their focus on six traits that could be reliably measured on all of the fossils including simple measurements like the relative length of the bone as a proxy for stride length and more sophisticated analyses that simulated mechanical stress under different weight bearing scenarios to estimate humerus strength.

"If you have an equal representation of all the functional traits you can map out how the performance changes as you go from one adaptive peak to another, " Dickson explained. Using computational optimization the team was able to reveal the exact combination of functional traits that maximized performance for aquatic fish, terrestrial tetrapods, and the earliest tetrapods. Their results showed that the earliest tetrapods had a unique combination of functional traits, but did not conform to their own adaptive peak.

"What we found was that the humeri of the earliest tetrapods clustered at the base of the terrestrial landscape, " said Pierce. "indicating increasing performance for moving on land. But these animals had only evolved a limited set of functional traits for effective terrestrial walking."

The researchers suggest that the ability to move on land may have been limited due to selection on other traits, like feeding in water, that tied early tetrapods to their ancestral aquatic habitat. Once tetrapods broke free of this constraint, the humerus was free to evolve morphologies and functions that enhanced limb-based locomotion and the eventual invasion of terrestrial ecosystems

"Our study provides the first quantitative, high-resolution insight into the evolution of terrestrial locomotion across the water-land transition, " said Dickson. "It also provides a prediction of when and how [the transition] happened and what functions were important in the transition, at least in the humerus."

"Moving forward, we are interested in extending our research to other parts of the tetrapod skeleton, " Pierce said. "For instance, it has been suggested that the forelimbs became terrestrially capable before the hindlimbs and our novel methodology can be used to help test that hypothesis."

Dickson recently started as a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Animal Locomotion lab at Duke University, but continues to collaborate with Pierce and her lab members on further studies involving the use of these methods on other parts of the skeleton and fossil record.