USA:s president Donald Trump gjorde falska påståenden om omfattande valfusk under presidentvalet 2020. UNSW Psychology forskare har nu hittat ett sätt för människor att inte bli lurade med så kallade "falska nyheter" från en enda källa. Kredit:Shutterstock

Om fler människor sa till dig att något var sant, skulle du tro att du tenderar att tro det.

Inte enligt en studie från Yale University från 2019 som visade att människor tror på en enda informationskälla som upprepas över många kanaler (en "falsk konsensus"), lika lätt som att flera personer berättar något för dem baserat på många oberoende originalkällor (en "true consensus").

Fyndet visade hur desinformation kan stärkas, och det fick konsekvenser för viktiga beslut vi fattar baserat på råd vi får från platser som regeringar och media om information som vaccinationer, bära masker under pandemin eller till och med vem vi röstar på i ett val .

Fyndet från 2019 "illusion av konsensus" har fascinerat postdoktor vid UNSW Science's School of Psychology, Saoirse Connor Desai, som har testat illusionsfyndet och hittat ett sätt för människor att inte bli lurade med så kallade "falska nyheter" från en enda källa.

Hennes teams studie har publicerats i Cognition .

"Vi fann att illusioner kan reduceras när vi ger människor information om hur de ursprungliga källorna använde bevis för att komma fram till sina slutsatser," säger Dr. Connor Desai.

Hon säger att fyndet är särskilt relevant för bästa praxis för vetenskapskommunikation – t.ex. hur beslutsfattare eller media presenterar experter på vetenskapliga bevis eller forskning.

Till exempel upprepar över 80 procent av bloggarna om klimatförändringar påståenden från en enda person som säger sig vara en "isbjörnsexpert".

"Du kan ha en situation där ett missvisande hälsoförslag upprepas genom flera kanaler, vilket kan påverka människor att förlita sig på den informationen mer än de borde göra, eftersom de tror att det finns bevis för det, eller de tror att det finns en konsensus." Dr. Connor Desai säger.

"Men vårt resultat visar att om du kan förklara för människor var din information kommer ifrån, och hur de ursprungliga källorna kom fram till sina slutsatser, stärker det deras förmåga att identifiera en "sann konsensus."

Dr. Connor Desai säger att resultaten från Yale-studien var överraskande för henne, "eftersom det verkade vara en anklagelse om mänsklig förmåga att skilja mellan sann konsensus och falsk konsensus."

"Den ursprungliga studien visade att människor rutinmässigt är dåliga på detta. Det fanns många situationer där de aldrig kunde se skillnaden mellan sann och falsk konsensus", säger hon.

"Det är problematiskt eftersom om människor hör en enda persons falska eller vilseledande uttalanden upprepade genom olika kanaler, kan de känna att uttalandet är mer giltigt än det är."

Dr. Connor Desai says an example of this is multiple independent experts agreeing that Ivermectin should not be used to treat COVID-19 (true consensus), versus a single group or individual saying that people should use it as an anti-viral drug (false consensus).

How the study was conducted

The aim of the UNSW study was to understand why people believe false information when it's repeated.

"Our main goal was to establish whether one reason that people are equally convinced by true and false consensus is that they assume that different sources share data or methodologies," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Do they understand there is potentially more evidence when you have multiple experts saying the same thing?"

The UNSW researchers conducted several experiments.

The first experiment replicated the 2019 Yale study, which saw participants given a variety of articles about a fictional tax policy which took positive, negative, or neutral stances, and then asked to what extent they agreed the proposal would improve the economy.

It replicated the "illusion of consensus" where people are equally convinced by one piece of evidence as they are by many pieces of evidence but added a new condition where they told people who saw a "true consensus" that the sources had used different data and methods to arrive at their conclusions.

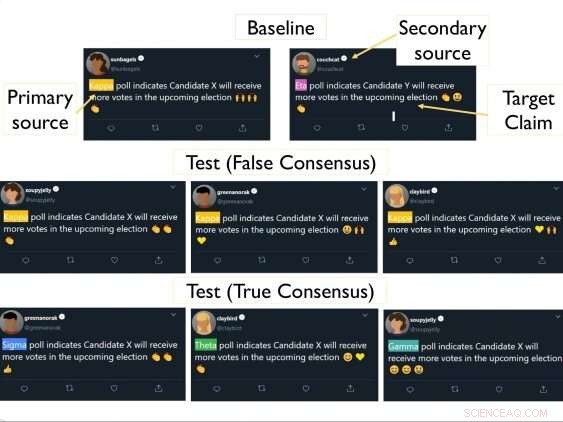

An example of the made up Twitter posts used in the study.

The result was a reduction in the illusion of consensus.

"People were more convinced by true consensus than false consensus."

In another experiment, 200 participants were given information about an election in a fictional foreign democratic country.

They were shown fictional Twitter posts from news outlets that said which candidates would get more votes in the election:some sourced the same or different pollsters to predict a candidate would win, while another tweet said a different contender would win.

But in the true consensus Twitter posts, they gave people a scenario in which it was clear that different primary sources worked independently and used different data to arrive at their conclusions.

"We expected that many people would be more familiar with such polls and would realize that looking at multiple different polls would be a better way of predicting the election result than just seeing a single poll multiple times," Dr. Connor Desai says.

After reading the tweets, participants rated which candidate would win based on the polling predictions.

"It seemed that people were more convinced by a true consensus than a false consensus when they understood the pollsters had gathered evidence independently of one another," Professor of Cognitive Psychology in the School of Psychology, Brett Hayes says.

"Our results suggest that people do see claims endorsed by multiple sources as stronger when they believe these sources really are independent of one another."

The researchers later replicated and extended the tweet study with 365 more participants.

"This time we had a condition where the tweets came from individual people who showed their endorsement of the polls using emojis," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Regardless of whether the tweets came from news outlets, or individual tweeters, people were more convinced by true than false consensus when the relationship between sources was unambiguous."

False consensus not completely discounted

But the researchers also found the participants didn't completely discount false consensus.

"There are at least two possible explanations for this effect," Dr. Connor Desai said.

"The first is that such repetition simply increases the familiarity of the claim—enhancing its memory representation, and this is sufficient to increase confidence.

"The second is that people may make inferences about why a claim is repeated because the source believed it was the most reputable or provided the strongest evidence.

"For instance, if different news channels all cite the same expert you might think that they're citing the same person because they are the most qualified to talk about whatever it is they're talking about."

Dr. Connor Desai plans to next look at why some communication strategies are more effective than others, and if repeating information is always effective.

"Is there a point where there's too much consensus, and people become suspicious?" she says.

"Can you correct a 'false consensus' by pointing out that it's often better to get information from multiple independent sources? These are the kinds of strategies we wish to look into."