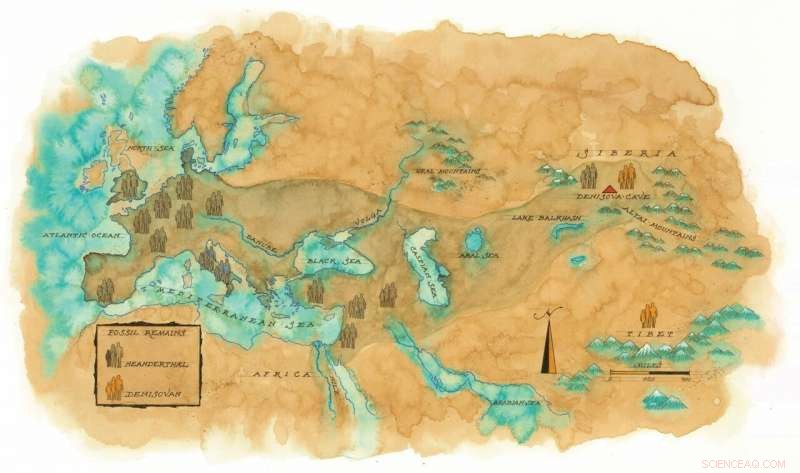

Joshua Akey, professor vid Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, använder en forskningsmetod som han kallar genetisk arkeologi för att förändra hur vi lär oss om vårt förflutna. Fossila bevis illustrerar spridningen av två sedan länge utdöda homininarter, Neandertalare och denisovaner. Moderna människor bär gener från dessa arter, vilket indikerar att våra direkta förfäder mötte och parade sig med arkaiska människor. Kredit:Michael Francis Reagan

Under större delen av vår evolutionära historia – under större delen av tiden har anatomiskt moderna människor varit på jorden – har vi delat planeten med andra arter av människor. Det har bara varit under de senaste 30, 000 år, blotta blinkandet med ett evolutionärt öga, att moderna människor har ockuperat planeten som den enda representanten för homininlinjen.

Men vi bär bevis på dessa andra arter med oss. I vårt genom finns spår av genetiskt material från en mängd olika forntida människor som inte längre existerar. Dessa spår avslöjar en lång historia av sammanblandning, som våra direkta förfäder mötte – och parade sig med – arkaiska människor. När vi använder allt mer komplex teknik för att studera dessa genetiska kopplingar, vi lär oss inte bara om dessa utdöda människor utan också om den större bilden av hur vi utvecklades som art.

Joshua Akey, professor vid Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, leder ansträngningarna att förstå denna större bild. Han kallar sin forskningsmetod för genetisk arkeologi, och det förändrar hur vi lär oss om vårt förflutna. "Vi kan gräva ut olika typer av människor inte från smuts och fossiler utan direkt från DNA, " han sa.

Genom att kombinera sin expertis inom biologi och darwinistisk evolution med beräknings- och statistiska metoder, Akey studerar de genetiska sambanden mellan moderna människor och två arter av utdöda homininer:neandertalare, de klassiska "grottmännen" inom paleoantropologin; och Denisovans, en nyligen upptäckt arkaisk människa. Akeys forskning avslöjar en komplex historia av blandningen av tidiga människor, indikerar flera årtusenden av befolkningsrörelser över hela världen.

"Det finns ofta en klyfta mellan forskarna som går ut och samlar in exotiska prover och forskarna som gör riktigt kreativ teori och dataanalys, och han har gjort båda, sa Kelley Harris, en före detta kollega till Akey's som nu är biträdande professor i genomvetenskap vid University of Washington.

Som många av oss, Akey har länge varit intresserad av hur den mänskliga arten utvecklats. "Människor vill lära sig om sitt förflutna, " sa han. "Men ännu mer än så, vi vill veta vad det innebär att vara människa."

Denna nyfikenhet följde Akey under hela hans skolgång. Under sitt doktorandarbete vid University of Texas Health Science Center i Houston i slutet av 1990-talet, han tittade på hur samtida människor i olika delar av världen var genetiskt släkt med varandra, och använde tidiga gensekvenseringsmetoder för att försöka förstå dessa samband.

Gensekvenserare är enheter som bestämmer ordningen för de fyra kemiska baserna (A, T, C och G) som utgör DNA-molekylen. Genom att bestämma ordningen för dessa baser, analytiker kan identifiera den genetiska information som kodas i en DNA-sträng.

Sedan 1990-talet, dock, gensekvenseringstekniken har utvecklats dramatiskt. En ny teknik känd som nästa generations sekvensering togs i bruk omkring 2010 och gjorde det möjligt för forskare att studera ett mycket stort antal genetiska sekvenser i det mänskliga genomet. Det tog 10 år att sekvensera det första mänskliga genomet, men dessa nya maskiner får hela genomsekvensdata från tusentals individer på bara några timmar. "När nästa generations sekvenseringsteknik började bli den dominerande kraften inom genetik, "Akey sa, "det förändrade hela fältet totalt. Det är svårt att överskatta hur dramatisk denna teknik har varit."

Omfattningen av de data som nu kan analyseras har gjort det möjligt för forskare att ta upp en hel rad nya frågor som inte skulle ha varit möjliga med den tidigare tekniken.

Joshua Akey och hans team använder gensekvenseringsteknologier för att avslöja ny information om ålderdomliga mänskliga linjer såväl som vår egen evolutionära historia. Credit:Sameer A. Khan/Fotobuddy

One of these questions is the relationship between modern humans and archaic humans, such as Neanderthals. Faktiskt, this question fostered a vigorous debate about whether modern humans carried genes from Neanderthals. Under många år, the opinions of researchers—both pro and con—ticked back and forth like a metronome.

Gradvis, dock, a few researchers—including geneticists Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute in Germany and his colleague Richard (Ed) Green of the University of California-Santa Cruz—began to demonstrate strong evidence that, indeed, there had been gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans. In a 2010 paper, these researchers estimated that people of non-African ancestry had about 2% Neanderthal ancestry.

Neanderthals lived in a wide geographical swath across Europe, the Near East and Central Asia before dying out around 30, 000 år sedan. They lived alongside anatomically modern humans, who evolved in Africa some 200, 000 år sedan. The archaeological record shows that Neanderthals were adept at making stone tools and developed a number of physical traits that uniquely adapted them to cold, dark climates, such as broad noses, thick body hair and large eyes.

Following on the heels of Pääbo and Green's Neanderthal research, Akey and a colleague, Benjamin Vernot, published a paper in Science looking at recovering Neanderthal sequences from the genome of modern humans. Geneticist David Reich of Harvard University published a similar paper in Nature, och, together, the two papers provided the first data employing the modern genome to investigate our link with Neanderthals.

Using the genetic variation in contemporary populations to learn about things that happened in the past involves scrutinizing the modern human genome for gene sequences that display traits expected to have been inherited from a different type of human. Akey and his colleagues then take those sequences and compare them to the Neanderthal genome, looking for a match.

Using this technique, Akey has been able to uncover a rich human legacy of genetic interconnections on a scale previously unconceived. As stated, while the available evidence suggests that non-Africans carry about 2% of Neanderthal genes, Africans, who were once believed not to have any connections with Neanderthals, actually have approximately 0.5% Neanderthal genes. Researchers have further discovered that the Neanderthal genome has contributed to several diseases seen in modern human populations, such as diabetes, arthritis and celiac disease. By the same token, some genes inherited from Neanderthals have proven beneficial or neutral, such as genes for hair and skin color, sleep patterns and even mood.

Akey has also discovered genetic fingerprints that suggest our human ancestry contains species about which we know nothing or very little. The Denisovans are a case in point. An archaic form of human, they coexisted with anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals and interbred with both before going extinct. The first evidence of their existence came in 2008 when a finger bone was discovered in Denisova Cave in the remote Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. At first the bone was assumed to be Neanderthal because the cave contained evidence of these species. Consequently, it sat in a museum drawer in Leipzig, Tyskland, for many years before it was analyzed. But when it was, the researchers were dumbfounded. It wasn't a Neanderthal—it was a hitherto unknown type of ancient human. "The Denisovans are the first species ever identified directly from their DNA and not from fossil data, " Akey said.

Sen den tiden, continued genetic work—much of it conducted by Akey and his colleagues—has established that the closest living relatives of Denisovans are modern Melanesians, the inhabitants of the Melanesian islands of the western Pacific—places such as New Guinea, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Fiji. These populations carry between 4% and 6% of Denisovan genes, though they also carry Neanderthal genes.

Examples like this highlight one of the main features of our human lineage, Akey said, that admixture has been a defining feature of our history. "Throughout human history there's always been admixture, " Akey said. "Populations split and they come back together."

While there remains a lot of debate about the Denisovans, Akey believes they most likely were closely related to Neanderthals, perhaps an eastern version who split off from the latter sometime around 300, 000 or 400, 000 år sedan. Nyligen, genetic analysis of fossils from Denisova Cave has uncovered evidence of an offspring between a Neanderthal woman and a Denisovan male. The offspring was a female who lived approximately 90, 000 år sedan. By looking at this genetic trail, Akey and other researchers have been able to piece together a fascinating story of human evolution—one that is promising to rewrite our understanding of early human origins.

But there's so much more to discover, Akey said. "Even though we have sequenced probably 100, 000 genomes already, and we have pretty sophisticated tools for looking at that variation, the more we think about how to interpret genetic variation, the more we find these hidden stories in our DNA, " han sa.