Joshi Festival i Kalash-stammen i Pakistan, 14 maj 2011. Kredit:Shutterstock/Maharani afifah

Jag öppnar mina ögon för ljudet av en röst när det tvåmotoriga propellerflygplanet Pakistan Airlines flyger genom bergskedjan Hindu Kush, väster om det mäktiga Himalaya. Vi kryssar på 27 000 fot, men bergen runt oss verkar oroande nära och turbulensen har väckt mig under en 22 timmar lång resa till den mest avlägsna platsen i Pakistan – Kalash-dalarna i Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa-regionen.

Till vänster om mig ber en förvirrad kvinnlig passagerare tyst. På min omedelbara högra sida sitter min guide, översättare och vän Taleem Khan, en medlem av den polyteistiska Kalash-stammen som har cirka 3 500 personer. Det här var mannen som talade till mig när jag vaknade. Han lutar sig över igen och frågar, denna gång på engelska:"God morgon, bror. Mår du bra?"

"Prúst", (jag mår bra) svarar jag när jag blir mer medveten om min omgivning.

Det verkar inte som om planet sjunker; snarare känns det som om marken kommer upp för att möta oss. Och efter att planet har träffat landningsbanan, och passagerarna har stigit av, är chefen för Chitralpolisstationen där för att hälsa på oss. Vi tilldelas en poliseskort för vårt skydd (fyra poliser som arbetar i tvåskift), eftersom det finns mycket reella hot mot forskare och journalister i denna del av världen.

Först då kan vi ge oss ut på den andra etappen av vår resa:en tvåtimmars jeeptur till Kalash-dalarna på en grusväg som har höga berg på ena sidan, och en 200 fot nedstigning i Bumburetfloden på den andra. De intensiva färgerna och livskraften på platsen måste levas för att förstås.

Syftet med denna forskningsresa, genomförd av Durham University Music and Science Lab, är att upptäcka hur den känslomässiga uppfattningen av musik kan påverkas av lyssnarnas kulturella bakgrund, och att undersöka om det finns några universella aspekter på känslor som förmedlas av musik. . För att hjälpa oss förstå denna fråga ville vi hitta människor som inte hade blivit utsatta för västerländsk kultur.

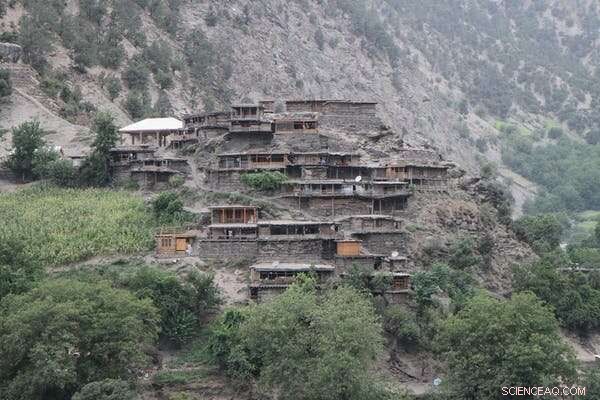

Byarna som ska vara vår verksamhetsbas är utspridda över tre dalar på gränsen mellan nordvästra Pakistan och Afghanistan. De är hem för ett antal stammar, även om de både nationellt och internationellt är kända som Kalash-dalarna (uppkallade efter Kalash-stammen). Trots sin relativt lilla befolkning skiljer deras unika seder, polyteistiska religion, ritualer och musik dem från sina grannar.

Vägen från Chitral till centrala Kalash Valley. Kredit:George Athanasopoulos, Författare tillhandahålls

I fältet

Jag har forskat på platser som Papua Nya Guinea, Japan och Grekland. Sanningen är att fältarbete ofta är dyrt, potentiellt farligt och ibland till och med livshotande.

Men hur svårt det än är att genomföra experiment när man står inför språkliga och kulturella hinder, skulle bristen på en stabil elförsörjning för att ladda våra batterier vara bland de svåraste hindren för oss att övervinna på denna resa. Data kan endast samlas in med hjälp och vilja från lokalbefolkningen. Människorna vi träffade gjorde bokstavligen den extra milen för oss (faktiskt ytterligare 16 mil) så att vi kunde ladda vår utrustning på närmaste stad med ström. Det finns lite infrastruktur i denna region i Pakistan. Det lokala vattenkraftverket ger 200W för varje hushåll på natten, men det är benäget att fungera fel på grund av flottsam efter varje nederbörd, vilket gör att det slutar fungera varannan dag.

När vi väl övervunnit de tekniska problemen var vi redo att påbörja vår musikaliska undersökning. När vi lyssnar på musik förlitar vi oss mycket på vårt minne av den musik vi har hört under hela våra liv. Människor runt om i världen använder olika typer av musik för olika ändamål. Och kulturer har sina egna etablerade sätt att uttrycka teman och känslor genom musik, precis som de har utvecklat preferenser för vissa musikaliska harmonier. Kulturella traditioner formar vilka musikaliska harmonier som förmedlar lycka och - upp till en viss punkt - hur mycket harmonisk dissonans som uppskattas. Tänk till exempel på den glada stämningen i The Beatles Here Comes the Sun och jämför den med den olycksbådande hårdheten i Bernard Herrmanns partitur för den ökända duschscenen i Hitchcocks Psycho.

Så eftersom vår forskning syftade till att upptäcka hur den känslomässiga uppfattningen av musik kan påverkas av lyssnarnas kulturella bakgrund, var vårt första mål att lokalisera deltagare som inte var överväldigande exponerade för västerländsk musik. Detta är lättare sagt än gjort, på grund av globaliseringens övergripande effekt och det inflytande som västerländska musikstilar har på världskulturen. En bra utgångspunkt var att leta efter platser utan stabil elförsörjning och väldigt få radiostationer. Det skulle vanligtvis betyda dålig eller ingen internetanslutning med begränsad tillgång till musikplattformar online – eller, faktiskt, alla andra sätt att komma åt global musik.

En fördel med vårt valda läge var att den omgivande kulturen inte var västerländsk, utan snarare i en helt annan kulturell sfär. Punjabikulturen är huvudfåran i Pakistan, eftersom Punjabi är den största etniska gruppen. Men Khowari-kulturen dominerar i Kalash-dalarna. Mindre än 2 % talar urdu, Pakistans lingua franca, som sitt modersmål. Kho-folket (en grannstam till Kalashen), uppgår till cirka 300 000 och var en del av kungariket Chitral, en furstlig stat som först var en del av den brittiska Raj, och sedan av den islamiska republiken Pakistan fram till 1969. Västvärlden ses av samhällena där som något "annat", "främmande" och "inte vårt eget".

Det andra syftet var att lokalisera personer vars egen musik består av en etablerad, inhemsk framförandetradition där uttryck av känslor genom musik sker på ett jämförbart sätt västerut. Det beror på att även om vi försökte undkomma västerländsk musiks inflytande på lokala musikaliska praktiker, var det ändå viktigt att våra deltagare förstod att musik potentiellt kunde förmedla olika känslor.

Träbostäder i Rumburdalen, en av de tre dalarna som bebos av Kalashfolket i Chitral District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Kredit:Shutterstock/knovakov

Slutligen behövde vi en plats där våra frågor kunde ställas på ett sätt som skulle göra det möjligt för deltagare från olika kulturer att bedöma känslomässiga uttryck i både västerländsk och icke-västerländsk musik.

För Kalash är musik inte ett tidsfördriv; det är en kulturell identifierare. Det är en oskiljaktig aspekt av både rituell och icke-rituell praktik, av födseln och av livet. When someone dies, they are sent off to the sounds of music and dancing, as their life story and deeds are retold.

Meanwhile, the Kho people view music as one of the "polite" and refined arts. They use it to highlight the best aspects of their poetry. Their evening gatherings, typically held after dark in the homes of prominent members of the community, are comparable to salon gatherings in Enlightenment Europe, in which music, poetry and even the nature of the act and experience of thought are discussed. I was often left to marvel at how regularly men, who seemingly could bend steel with their piercing gaze, were moved to tears by a simple melody, a verse, or the silence which followed when a particular piece of music had just ended.

It was also important to find people who understood the concept of harmonic consonance and dissonance—that is, the relative attractiveness and unattractiveness of harmonies. This is something which can be easily done by observing whether local musical practices include multiple, simultaneous voices singing together one or more melodic lines. After running our experiments with British participants, we came to the Kalash and Kho communities to see how non-western populations perceive these same harmonies.

Our task was simple:expose our participants from these remote tribes to voice and music recordings which varied in emotional intensity and context, as well as some artificial music samples we had put together.

Major and minor

A mode is the language or vocabulary that a piece of music is written in, while a chord is a set of pitches which sound together. The two most common modes in western music are major and minor. Here Comes the Sun by The Beatles is a song in a major scale, using only major chords, while Call Out My Name by the Weeknd is a song in a minor scale, which uses only minor chords. In western music, the major scale is usually associated with joy and happiness, while the minor scale is often associated with sadness.

Right away we found that people from the two tribes were reacting to major and minor modes in a completely different manner to our UK participants. Our voice recordings, in Urdu and German (a language very few here would be familiar with), were perfectly understood in terms of their emotional context and were rated accordingly. But it was less than clear cut when we started introducing the musical stimuli, as major and minor chords did not seem to get the same type of emotional reaction from the tribes in northwest Pakistan as they do in the west.

We began by playing them music from their own culture and asked them to rate it in terms of its emotional context; a task which they performed excellently. Then we exposed them to music which they had never heard before, ranging from West Coast Jazz and classical music to Moroccan Tuareg music and Eurovision pop songs.

While commonalities certainly exist—after all, no army marches to war singing softly, and no parent screams their children to sleep—the differences were astounding. How could it be that Rossini's humorous comic operas, which have been bringing laughter and joy to western audiences for almost 200 years, were seen by our Kho and Kalash participants to convey less happiness than 1980s speed metal?

We were always aware that the information our participants provided us with had to be placed in context. We needed to get an insider perspective on their train of thought regarding the perceived emotions.

Essentially, we were trying to understand the reasons behind their choices and ratings. After countless repetitions of our experiments and procedures and making sure that our participants had understood the tasks that we were asking them to do, the possibility started to emerge that they simply did not prefer the consonance of the most common western harmonies.

Not only that, but they would go so far as to dismiss it as sounding "foreign." Indeed, a recurring trope when responding to the major chord was that it was "strange" and "unnatural," like "European music." That it was "not our music."

What is natural and what is cultural?

Once back from the field, our research team met up and together with my colleagues Dr. Imre Lahdelma and Professor Tuomas Eerola we started interpreting the data and double checking the preliminary results by putting them through extensive quality checks and number crunching with rigorous statistical tests. Our report on the perception of single chords shows how the Khalash and Kho tribes perceived the major chord as unpleasant and negative, and the minor chord as pleasant and positive.

To our astonishment, the only thing the western and the non-western responses had in common was the universal aversion to highly dissonant chords. The finding of a lack of preference for consonant harmonies is in line with previous cross-cultural research investigating how consonance and dissonance are perceived among the Tsimané, an indigenous population living in the Amazon rainforest of Bolivia with limited exposure to western culture. Notably, however, the experiment conducted on the Tsimané did not include highly dissonant harmonies in the stimuli. So the study's conclusion of an indifference to both consonance and dissonance might have been premature in the light of our own findings.

When it comes to emotional perception in music, it is apparent that a large amount of human emotions can be communicated across cultures at least on a basic level of recognition. Listeners who are familiar with a specific musical culture have a clear advantage over those unfamiliar with it—especially when it comes to understanding the emotional connotations of the music.

But our results demonstrated that the harmonic background of a melody also plays a very important role in how it is emotionally perceived. See, for example, Victor Borge's Beethoven variation on the melody of Happy Birthday, which on its own is associated with joy, but when the harmonic background and mode changes the piece is given an entirely different mood.

Then there is something we call "acoustic roughness," which also seems to play an important role in harmony perception—even across cultures. Roughness denotes the sound quality that arises when musical pitches are so close together that the ear cannot fully resolve them. This unpleasant sound sensation is what Bernard Herrmann so masterfully uses in the aforementioned shower scene in Psycho. This acoustic roughness phenomenon has a biologically determined cause in how the inner ear functions and its perception is likely to be common to all humans.

According to our findings, harmonisations of melodies that are high in roughness are perceived to convey more energy and dominance—even when listeners have never heard similar music before. This attribute has an affect on how music is emotionally perceived, particularly when listeners lack any western associations between specific music genres and their connotations.

For example, the Bach chorale harmonization in major mode of the simple melody below was perceived as conveying happiness only to our British participants. Our Kalash and Kho participants did not perceive this particular style to convey happiness to a greater degree than other harmonisations.

The wholetone harmonization below, on the other hand, was perceived by all listeners—western and non-western alike—to be highly energetic and dominant in relation to the other styles. Energy, in this context, refers to how music may be perceived to be active and "awake," while dominance relates to how powerful and imposing a piece of music is perceived to be.

Carl Orff's O Fortuna is a good example of a highly energetic and dominant piece of music for a western listener, while a soft lullaby by Johannes Brahms would not be ranked high in terms of dominance or energy. At the same time, we noted that anger correlated particularly well with high levels of roughness across all groups and for all types of real (for example, the Heavy Metal stimuli we used) or artificial music (such as the wholetone harmonization below) that the participants were exposed to.

So, our results show both with single, isolated chords and with longer harmonisations that the preference for consonance and the major-happy, minor-sad distinction seems to be culturally dependent. These results are striking in the light of tradition handed down from generation to generation in music theory and research. Western music theory has assumed that because we perceive certain harmonies as pleasant or cheerful this mode of perception must be governed by some universal law of nature, and this line of thinking persists even in contemporary scholarship.

Indeed, the prominent 18th century music theorist and composer Jean-Philippe Rameau advocated that the major chord is the "perfect" chord, while the later music theorist and critic Heinrich Schenker concluded that the major is "natural" as opposed to the "artificial" minor.

But years of research evidence now shows that it is safe to assume that the previous conclusions of the "naturalness" of harmony perception were uninformed assumptions, and failed even to attempt to take into account how non-western populations perceive western music and harmony.

Just as in language we have letters that build up words and sentences, so in music we have modes. The mode is the vocabulary of a particular melody. One erroneous assumption is that music consists of only the major and minor mode, as these are largely prevalent in western mainstream pop music.

In the music of the region where we conducted our research, there are a number of different, additional modes which provide a wide range of shades and grades of emotion, whose connotation may change not only by core musical parameters such as tempo or loudness, but also by a variety of extra-musical parameters (performance setting, identity, age and gender of the musicians).

For example, a video of the late Dr. Lloyd Miller playing a piano tuned in the Persian Segah dastgah mode shows how so many other modes are available to express emotion. The major and minor mode conventions that we consider as established in western tonal music are but one possibility in a specific cultural framework. They are not a universal norm.

Why is this important?

Research has the potential to uncover how we live and interact with music, and what it does to us and for us. It is one of the elements that makes the human experience more whole. Whatever exceptions exist, they are enforced and not spontaneous, and music, in some form, is present in all human cultures. The more we investigate music around the world and how it affects people, the more we learn about ourselves as a species and what makes us feel .

Our findings provide insights, not only into intriguing cultural variations regarding how music is perceived across cultures, but also how we respond to music from cultures which are not our own. Can we not appreciate the beauty of a melody from a different culture, even if we are ignorant to the meaning of its lyrics? There are more things that connect us through music than set us apart.

When it comes to musical practices, cultural norms can appear strange when viewed from an outsider's perspective. For example, we observed a Kalash funeral where there was lots of fast-paced music and highly-energetic dancing. A western listener might wonder how it is possible to dance with such vivacity to music which is fast, rough and atonal—at a funeral.

But at the same time, a Kalash observer might marvel at the sombreness and quietness of a western funeral:was the deceased a person of so little importance that no sacrifices, honorary poems, praise songs and loud music and dancing were performed in their memory? As we assess the data captured in the field a world away from our own, we become more aware of the way music shapes the stories of the people who make it, and how it is shaped by culture itself.

After we had said our goodbyes to our Kalash and Kho hosts, we boarded a truck, drove over the dangerous Lowari Pass from Chitral to Dir, and then traveled to Islamabad and on to Europe. And throughout the trip, I had the words of a Khowari song in my mind:"The old path, I burn it, it is warm like my hands. In the young world, you will find me."