Kredit:Shutterstock

När vi fäste små, ryggsäcksliknande spårningsenheter till fem australiensiska skator för en pilotstudie, förväntade vi oss inte att upptäcka ett helt nytt socialt beteende som sällan sett hos fåglar.

Vårt mål var att lära oss mer om dessa mycket intelligenta fåglars rörelser och sociala dynamik, och att testa dessa nya, hållbara och återanvändbara enheter. Istället överlistade fåglarna oss.

Som vår nya forskningsartikel förklarar började skatorna visa bevis på ett samarbetsvilligt "räddnings"-beteende för att hjälpa varandra att ta bort spåraren.

Även om vi är bekanta med att skator är intelligenta och sociala varelser, var detta det första fallet vi kände till som visade den här typen av till synes altruistiskt beteende:att hjälpa en annan medlem i gruppen utan att få en omedelbar, påtaglig belöning.

Testar nya spännande enheter

Som akademiska forskare är vi vana vid att experiment går snett på ett eller annat sätt. Utgångna ämnen, trasig utrustning, kontaminerade prover, ett oplanerat strömavbrott – allt detta kan sätta tillbaka månader (eller till och med år) av noggrant planerad forskning.

För oss som studerar djur, och framför allt beteende, är oförutsägbarhet en del av arbetsbeskrivningen. Detta är anledningen till att vi ofta kräver pilotstudier.

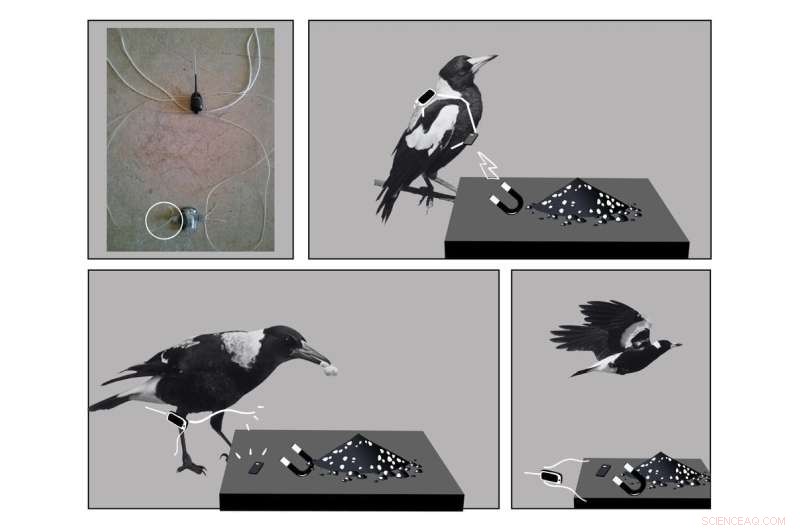

En av spårarna fäste vi på fem skator, som väger mindre än ett gram. Kredit:Dominique Potvin, författare tillhandahållen

Vår pilotstudie var en av de första i sitt slag – de flesta spårare är för stora för att passa på medelstora till små fåglar, och de som har en tendens att ha mycket begränsad kapacitet för datalagring eller batteritid. De tenderar också att endast vara engångsbruk.

En ny aspekt av vår forskning var designen av selen som höll spåraren. Vi tog fram en metod som inte krävde att fåglar fångas igen för att ladda ner värdefull data eller återanvända de små enheterna.

Vi tränade en grupp lokala skator att komma till en markmatningsstation utomhus som antingen trådlöst kan ladda spårarens batteri, ladda ner data eller släppa spåraren och selen med hjälp av en magnet.

Selen var tuff, med bara en svag punkt där magneten kunde fungera. För att ta bort selen behövde man den där magneten, eller någon riktigt bra sax. Vi var entusiastiska över designen, eftersom den öppnade många möjligheter till effektivitet och gjorde att mycket data kunde samlas in.

We wanted to see if the new design would work as planned, and discover what kind of data we could gather. How far did magpies go? Did they have patterns or schedules throughout the day in terms of movement, and socialising? How did age, sex or dominance rank affect their activities?

All this could be uncovered using the tiny trackers—weighing less than one gram—we successfully fitted five of the magpies with. All we had to do was wait, and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to gather the valuable data.

It was not to be

Many animals that live in societies cooperate with one another to ensure the health, safety and survival of the group. In fact, cognitive ability and social cooperation has been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have an increased capacity for problem solving, such as hyenas, spotted wrasse, and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. As a generalist species that excels in problem solving, it has adapted well to the extreme changes to their habitat from humans.

Australian magpies generally live in social groups of between two and 12 individuals, cooperatively occupying and defending their territory through song choruses and aggressive behaviors (such as swooping). These birds also breed cooperatively, with older siblings helping to raise young.

During our pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies team up to solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we witnessed an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness off of a younger bird.

Within hours, most of the other trackers had been removed. By day 3, even the dominant male of the group had its tracker successfully dismantled.

We don't know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never read about any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

Our new tracker design was innovative, allowing a magnet to release the harness. Credit:Dominique Potvin, Author provided

The birds needed to problem solve, possibly testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness with their bill. They also needed to willingly help other individuals, and accept help.

The only other similar example of this type of behavior we could find in the literature was that of Seychelles warblers helping release others in their social group from sticky Pisonia seed clusters. This is a very rare behavior termed "rescuing."

Saving magpies

So far, most bird species that have been tracked haven't necessarily been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers, such as waterfowl and raptors. We never considered the magpies may perceive the tracker as some kind of parasite that requires removal.

Tracking magpies is crucial for conservation efforts, as these birds are vulnerable to the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves under climate change.

In a study published this week, Perth researchers showed the survival rate of magpie chicks in heatwaves can be as low as 10%.

Importantly, they also found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance for tasks such as foraging. This might mean cooperative behaviors become even more important in a continuously warming climate.

Just like magpies, we scientists are always learning to problem solve. Now we need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioral data to help magpies survive in a changing world.