Hur kan forskare avgöra om manliga och kvinnliga dinosaurier, som stegosaurien, var olika? Kredit:Susannah Maidment et al. &Natural History Museum, London, CC BY

Hos de flesta djurarter skiljer sig hanar och honor. Detta gäller för människor och andra däggdjur, såväl som för många arter av fåglar, fiskar och reptiler. Men hur är det med dinosaurier? 2015 föreslog jag att variationen i stegosauriernas ikoniska bakplattor berodde på könsskillnader.

Jag blev förvånad över hur starkt några av mina kollegor inte var överens och hävdade att skillnader mellan kön, kallad sexuell dimorfism, inte existerade hos dinosaurier.

Jag är paleontolog, och debatten som väcktes av mitt 2015-dokument har fått mig att ompröva hur forskare som studerar forntida djur använder statistik.

Den begränsade fossilregistreringen gör det svårt att deklarera om en dinosaurie var sexuellt dimorf. Men jag och några andra inom mitt område börjar gå bort från traditionellt svart-eller-vitt statistiskt tänkande som förlitar sig på p-värden och statistisk signifikans för att definiera ett sant fynd. Istället för att bara leta efter ja eller nej-svar, börjar vi överväga den uppskattade storleken på sexuell variation hos en art, graden av osäkerhet i den uppskattningen och hur dessa mått jämförs med andra arter. Detta tillvägagångssätt erbjuder en mer nyanserad analys av utmanande frågor inom paleontologi såväl som många andra vetenskapsområden.

Skillnader mellan män och kvinnor

Sexuell dimorfism är när män och honor av en viss art skiljer sig i genomsnitt i en viss egenskap - inte inklusive deras reproduktiva anatomi. Klassiska exempel är hur hjorthanar har horn och påfågelhanar har flashiga stjärtfjädrar, medan honorna saknar dessa egenskaper.

Dimorfism kan också vara subtil och oplansig. Ofta är skillnaden av grad, som skillnader i den genomsnittliga kroppsstorleken mellan hanar och honor – som hos gorillor. I dessa blygsamma fall använder forskare statistik för att avgöra om en egenskap skiljer sig i genomsnitt mellan män och kvinnor.

Hos många arter, som dessa mandarinänder, ser hanar (vänster) och honor (höger) väldigt olika ut. Kredit:Francis C. Franklin via WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA

Dinosauriedilemmat

Att studera sexuell dimorfism hos utdöda djur är fyllt av osäkerhet. Om du och jag oberoende gräver upp liknande fossiler av samma art, kommer de oundvikligen att vara något annorlunda. Dessa skillnader kan bero på kön, men de kan också drivas av ålder - unga fåglar är luddiga, vuxna fåglar är slanka. De kan också bero på genetik som inte är relaterad till sex, som ögonfärg hos människor.

If paleontologists had thousands of fossils to study of every species, the many sources of biological variation wouldn't matter as much. Unfortunately, the ravages of time have left the fossil record painfully incomplete, often with less than a dozen good specimens for large, extinct vertebrate species. Additionally, there is currently no way to identify the sex of an individual fossil except in rare cases where obvious clues exist, like eggs preserved within the body cavity.

So where does all this leave the debate on whether male and female dinosaurs had differences within traits? On the one hand, birds—which are direct descendants of dinosaurs—commonly show sexual dimorphism. So do crocodilians, dinosaurs' next closest living relatives. Evolutionary theory also predicts that, since dinosaurs reproduced with sperm and egg, there would be a benefit to sexual dimorphism.

These things all suggest that dinosaurs likely were sexually dimorphic. But in science you need to be quantitative. The challenge is that there is little in the way of statistically significant analyses of the fossil record to support dimorphism.

It’s possible that variation among individual dinosaurs of the same species could be due to sexual dimorphism, but there are rarely good enough samples to assert so using traditional statistics. Credit:James Ormiston, CC BY-ND

Statistical shifts

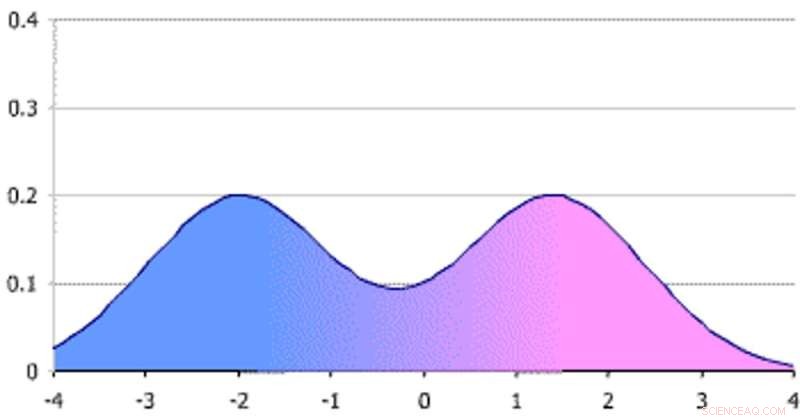

There are a couple of ways paleontologists could test for sexual dimorphism. They could look to see if there are statistically significant differences between fossils from presumed males and females, but there are very few specimens where researchers know the sex. Another method is to see whether there are two distinct groupings of a trait, called a bimodal distribution, which could suggest a difference between males and females.

To tell whether a perceived difference between two groups is true, scientists have traditionally used a tool called the p-value. P-values quantify the probability of a result being due to random chance. If a p-value is low enough, the result is deemed "statistically significant" and considered unlikely to have happened by chance.

But p-values can be heavily influenced by sample size and the design of the study, in addition to the actual degree of sexual dimorphism. Because of the very small sample size of fossils, relying on this statistical technique makes it exceedingly difficult to categorically proclaim what dinosaur species were dimorphic.

The weakness of the black-or-white approach that focuses solely on whether a result is statistically significant has led to hundreds of scientists calling to abandon significance testing with p-values in favor of something called effect size statistics. Using this approach, researchers would simply report the measured difference between two groups and the uncertainty in that measurement.

Very large sex differences can create a bimodal distribution that looks like two distinct groupings of a certain measurement. Credit:Maksim via WikimediaCommons, CC BY

Effect size statistics

I have begun to apply effect size statistics in my research on dinosaurs. My colleagues and I compared sexual dimorphism in body size between three different dinosaurs:the duck-billed Maiasaura, Tyrannosaurus rex and Psittacosaurus, a small relative of Triceratops. None of these species would be expected to show statistically significant size differences between males and females according to p-values. But that approach does not capture the nature of the variation within these species.

When we instead used effect size statistics, we were able to estimate that male and female Maiasaura demonstrate a greater difference in body mass compared to the other two species and that we had a higher confidence in this estimate as well. A few of the characteristics within the data helped reduce the uncertainty. First, we had a large number of Maiasaura fossils, from individuals of various ages. These bones very nicely fit with trajectories of how size changes as an individual grows from juvenile to adult, so we could control for differences due to age and instead focus on differences due to sex.

Additionally, the Maiasaura fossils all come from a single bone bed of individuals that died in the same place at the same time. This means that variation between individuals is likely not due to them being different species from different regions or time periods.

If my colleagues and I had approached the problem expecting a yes or no answer on whether males and females differed in size, we would have completely missed all of these intricacies. Effect size statistics allow researchers to produce much more nuanced and, I think, informative results. It is almost as much a difference in the philosophical approach to science as it is a mathematical one.

Using effect size statistics, researchers were able to determine that the duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura showed a larger amount of dimorphism with the least uncertainty in that estimate compared to other dinosaurs. Credit:Daderot via WikimediaCommons

Studying dinosaur dimorphism is not the only place p-values create issues. Many fields of science, including medicine and psychology, are having similar debates about issues in statistics and a worrying problem of unrepeatable studies.

Embracing uncertainty in data—rather than looking for black-or-white answers to questions like whether male and female dinosaurs were sexually dimorphic—can help elucidate dinosaur biology. But this shift in thinking may be felt far and wide across the sciences. A careful consideration of problems within statistics could have deep impacts across many fields.